Many passenger lists from a hundred years ago are available online, but it seems that those for ‘normal’ voyages within Europe were not preserved except in special circumstances. Thus I haven’t been able to establish exactly when the Fokine family left Britain for Norway in November 1914. Conceivably they left at the very beginning of December 1914; but Vitalii Fokine’s commentary to Fokine, Memoirs of a Ballet Master (London, Constable, c. 1961) suggests it was in the second half of November.

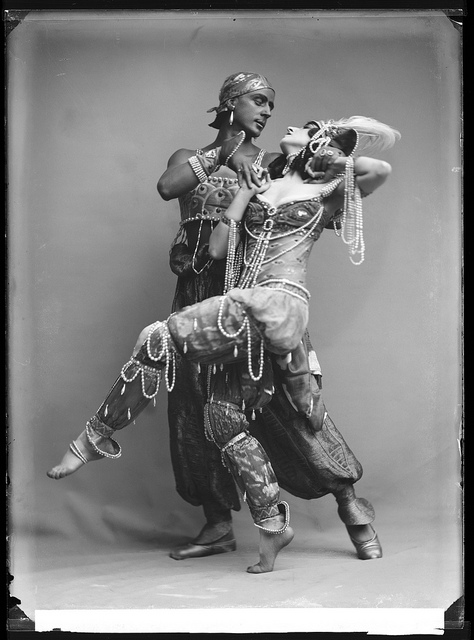

Michel and Vera Fokine in “Scheherazade”, 1914

(The Music And Theatre Library of Sweden, licensed under Creative Commons 2.0)

Michel and Vera Fokine were fabulous dancers; artists of absolute world significance. Calderon had acted as interpreter/fixer for Michel during Ballets Russes’s sensational visit to London in 1911 (see Juliet Nicolson, The Perfect Summer (London, John Murray, 2006)), but he had also written an unsigned piece about Ballets Russes in The Times of 24 June 1911 which has been widely reprinted ever since. He and Michel Fokine saw eye to eye. They were both polymaths, supremely gifted, had similar senses of humour, George had extensive useful contacts in English cultural circles, and was himself eager to write libretti for modern ballet. George and Kittie’s sculptor friend Emanuele Ordoño de Rosales also hit it off with Fokine, and made several figurines of him, viewable on the Web.

Fokine had broken with Diaghilev after the latter, for reasons connected with his relationship with Nijinsky, had attempted to ruin the first night of Fokine’s masterpiece Daphnis et Chloé in June 1912. However, Nijinsky was sacked by Diaghilev in late 1913 following Nijinsky’s wedding in Buenos Aires on 10 September. After complex negotiations, Fokine agreed in the winter of 1913/14 to become Diaghilev’s choreographer again and to create seven new works for him. The Ballets Russes season at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 8 June-25 July 1914, was one of the high points of Michel and Vera Fokine’s career, and the only occasion on which Fokine himself danced in London. It is possible that George Calderon translated for Fokine his long letter to The Times of 6 July 1914 in which Fokine set out his famous ‘Five Principles’ of modern ballet, although for stylistic reasons I am doubtful that it was Calderon’s work. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that before the Fokines left for Paris at the end of July 1914 George and Michel discussed the four or five ballet libretti that George had written so far.

The day that the Fokine family were due to leave Paris by rail for Russia through Germany, 3 August 1914, Germany declared war on France and they aborted their journey. (If they had not, they would have been held in Germany as Stanislavsky and some Moscow Arts actors were.) Instead, the Fokines moved to Biarritz close to the Spanish border. On 29 September George wrote to Kittie mentioning that he had had a letter from Michel. Unfortunately this letter has not survived, but George paraphrased: ‘Mme Fokin [the correct English transliteration] has got a bad chest again and they are thinking of leaving Biarritz for Spain (Switzerland is too full of Germans, they say).’ Judging from Vitalii Fokine’s commentary to his father’s memoirs, they crossed into Spain about then.

Michel Fokine used his time in Spain to study Spanish dance in depth — this later bore fruit in four of his ballet productions between 1916 and 1935. The Fokines’ intention was to return to Russia for the winter season at the Imperial Ballet in St Petersburg, as they had before. This they would do by steaming through the Mediterranean and Black Sea. However, on 29 October 1914 the Ottoman Empire came into the war on the Germans’ side and this shut off Russia’s Black Sea ports to European traffic. The Fokines decided the only way home to Russia was across the North Sea, despite the danger of attack from U-boats. They therefore returned to Paris and gathered themselves to move on to Britain and buy tickets to Norway (from Newcastle to Bergen?).

It was probably in the last week of November 1914 that the Fokine family visited Calderon at 42 Well Walk. Here is Kittie’s account:

The Fokins were terribly concerned to find him wounded. These two friends were always to us like birds of the air.

None of the ordinary things of life seemed to touch them. They adored each other and their little boy Vitalie, this and their wonderful art were literally all that counted to them. Besides [Michel Fokine] finding an understanding artistic sympathy in George, […] they became truly attached to him and we to them. She was an exquisite dancer. As anyone who has seen Fokin’s productions must know, he was full of a subtle and delicate humour, and George and he were planning many delicious ballets for the future.

On this occasion poor Madame was very distracted. She knew what would happen. The Germans would capture their steamer — Michel would be seized being of military age — and she and Vitalie would eventually be sent on to Russia — never to see Michel again. Mercifully this dire disaster did not fall upon them. […]

But these creatures of the Sun — for that is what they had made us feel they were — how could they ever exist in the world as the world had become — that is what we wondered.

In fact the Fokines were made of perdurable stuff. They had to be, to remain as focussed on their art as they were. In this respect they possibly present an instructive contrast to the quintessential Edwardian George Calderon. They worked tirelessly at their art, which they knew was at the cutting edge. Michel Fokine was always politically informed and never going to be manipulated by anyone. Early in 1918 he used the confidence of People’s Commissar of Enlightenment Anatolii Lunacharskii to get out of Russia and never return. Performing in Germany on one occasion in the 1930s, he refused to meet Hermann Goering in his box after the show, causing great consternation. He, Vera and Vitalii settled in the U.S.A., where inevitably they did not have an easy time, but they carved out a life for themselves through their own wonderful energy and dedication to their art.

The Fokine family made it safely to Norway in 1914, Michel and Vera performed in Scandinavia, and two months later they all reached St Petersburg. They never saw George Calderon again.

Next entry: Reactions

Related

The sexiest couple in Europe

Many passenger lists from a hundred years ago are available online, but it seems that those for ‘normal’ voyages within Europe were not preserved except in special circumstances. Thus I haven’t been able to establish exactly when the Fokine family left Britain for Norway in November 1914. Conceivably they left at the very beginning of December 1914; but Vitalii Fokine’s commentary to Fokine, Memoirs of a Ballet Master (London, Constable, c. 1961) suggests it was in the second half of November.

Michel and Vera Fokine in “Scheherazade”, 1914

(The Music And Theatre Library of Sweden, licensed under Creative Commons 2.0)

Michel and Vera Fokine were fabulous dancers; artists of absolute world significance. Calderon had acted as interpreter/fixer for Michel during Ballets Russes’s sensational visit to London in 1911 (see Juliet Nicolson, The Perfect Summer (London, John Murray, 2006)), but he had also written an unsigned piece about Ballets Russes in The Times of 24 June 1911 which has been widely reprinted ever since. He and Michel Fokine saw eye to eye. They were both polymaths, supremely gifted, had similar senses of humour, George had extensive useful contacts in English cultural circles, and was himself eager to write libretti for modern ballet. George and Kittie’s sculptor friend Emanuele Ordoño de Rosales also hit it off with Fokine, and made several figurines of him, viewable on the Web.

Fokine had broken with Diaghilev after the latter, for reasons connected with his relationship with Nijinsky, had attempted to ruin the first night of Fokine’s masterpiece Daphnis et Chloé in June 1912. However, Nijinsky was sacked by Diaghilev in late 1913 following Nijinsky’s wedding in Buenos Aires on 10 September. After complex negotiations, Fokine agreed in the winter of 1913/14 to become Diaghilev’s choreographer again and to create seven new works for him. The Ballets Russes season at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 8 June-25 July 1914, was one of the high points of Michel and Vera Fokine’s career, and the only occasion on which Fokine himself danced in London. It is possible that George Calderon translated for Fokine his long letter to The Times of 6 July 1914 in which Fokine set out his famous ‘Five Principles’ of modern ballet, although for stylistic reasons I am doubtful that it was Calderon’s work. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that before the Fokines left for Paris at the end of July 1914 George and Michel discussed the four or five ballet libretti that George had written so far.

The day that the Fokine family were due to leave Paris by rail for Russia through Germany, 3 August 1914, Germany declared war on France and they aborted their journey. (If they had not, they would have been held in Germany as Stanislavsky and some Moscow Arts actors were.) Instead, the Fokines moved to Biarritz close to the Spanish border. On 29 September George wrote to Kittie mentioning that he had had a letter from Michel. Unfortunately this letter has not survived, but George paraphrased: ‘Mme Fokin [the correct English transliteration] has got a bad chest again and they are thinking of leaving Biarritz for Spain (Switzerland is too full of Germans, they say).’ Judging from Vitalii Fokine’s commentary to his father’s memoirs, they crossed into Spain about then.

Michel Fokine used his time in Spain to study Spanish dance in depth — this later bore fruit in four of his ballet productions between 1916 and 1935. The Fokines’ intention was to return to Russia for the winter season at the Imperial Ballet in St Petersburg, as they had before. This they would do by steaming through the Mediterranean and Black Sea. However, on 29 October 1914 the Ottoman Empire came into the war on the Germans’ side and this shut off Russia’s Black Sea ports to European traffic. The Fokines decided the only way home to Russia was across the North Sea, despite the danger of attack from U-boats. They therefore returned to Paris and gathered themselves to move on to Britain and buy tickets to Norway (from Newcastle to Bergen?).

It was probably in the last week of November 1914 that the Fokine family visited Calderon at 42 Well Walk. Here is Kittie’s account:

In fact the Fokines were made of perdurable stuff. They had to be, to remain as focussed on their art as they were. In this respect they possibly present an instructive contrast to the quintessential Edwardian George Calderon. They worked tirelessly at their art, which they knew was at the cutting edge. Michel Fokine was always politically informed and never going to be manipulated by anyone. Early in 1918 he used the confidence of People’s Commissar of Enlightenment Anatolii Lunacharskii to get out of Russia and never return. Performing in Germany on one occasion in the 1930s, he refused to meet Hermann Goering in his box after the show, causing great consternation. He, Vera and Vitalii settled in the U.S.A., where inevitably they did not have an easy time, but they carved out a life for themselves through their own wonderful energy and dedication to their art.

The Fokine family made it safely to Norway in 1914, Michel and Vera performed in Scandinavia, and two months later they all reached St Petersburg. They never saw George Calderon again.

Next entry: Reactions

Share this:

Related