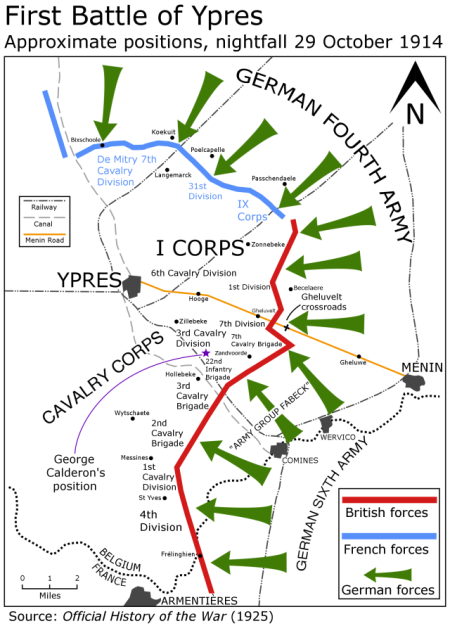

The German bombardment began at 5.30 a.m. and was concentrated on the Gheluvelt crossroads on the Menin Road (see map below). Falkenhayn’s plan was that having pushed the salient further in here, on 30th a general attack would be unleashed by the Fourth and Sixth Armies, during which an entirely new fighting force, Army Group Fabeck, would punch through the Messines Ridge to Hollebeke, completely breaking the British line. General Fabeck himself believed this would end the battle of Ypres and, even, the war. His six divisions had been brought down from the north over the previous week under cover of darkness, undetected by British reconnaissance. They meant that 23.5 German divisions were now confronting 11.5 Allied ones.

Gheluvelt crossroads was the junction between the British 1st and 7th Divisions and communications in the thick fog were poor. At 6.30 German troops penetrated the line and an hour later four battalions poured in after them. In fierce hand-to-hand fighting the British troops were forced back. As I Corps brought up reserves, the Germans widened their attack. In the immediate case, this meant the Zandvoorde section held by the 7th Cavalry Brigade and 22nd Infantry Brigade, between which George Calderon was yesterday delicately balanced well behind the lines.

George’s letter to Kittie yesterday is the last one from Ypres to have survived in the original. He seems to have written at least two more, extracts from which were published by Percy Lubbock in 1921. The first was given to the censor this morning. Evidently he had been to see his ‘old’ regiment, the Blues, and obtained written permission from them to transfer as Interpreter to the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

When I brought the officers of the R.W.R. the note saying I could join them, we altered the function. They were sitting at the roadside in a little group. The regiment has been blown to bits by Black Marias [large German howitzer shells]; about three hundred men remain and about eight officers. A captain commands the battalion. When I brought my note he asked me if I really wanted to interpret. I said No, what I wanted was a fighting job. ‘Then you’re just the man for us; sit down; we’re just reorganising the regiment.’ So I was attached as Junior Subaltern to A Company. The Senior Subaltern is a tired nice hungry boy of 18. (He gave me a Warwickshire badge that he happened to have in his pocket, while we were resting in turnips after a rush.) I went over the road to my billet and burnt my interpreter’s brassard. I was sick of interpreting; the work’s too hard for me. Then we started for the battle. Somebody got me a gun and equipment, and tied on my British warm [army greatcoat] with a bit of string; and off we went.

This would be at about 10.45 this morning, as Thompson Capper, commander of 7th Division, only learned of his line having been forced back at 10.15 (Ian F.W. Beckett, Ypres: The First Battle, 1914, London, Routledge, 2013, p. 149). The Warwickshires had spent the night near Klein Zillebeke, having had to withdraw part of their line under heavy fire at Zandvoorde on 27th. They were now being brought up to reoccupy those trenches, which it seems the Germans themselves had abandoned on 28th. But by 11.30 the order was actually to make contact with the Germans and counter-attack. Continuing in George’s words from his account written on 30 October:

We tootled ahead pretty gaily, flopping down at intervals. There were still British trenches ahead. At last we had just passed the last of them. I and another man trotted on to see what was there and thought we saw Germans on the left, half a mile away, moving in column. We came back and reported, advanced again with the whole crowd, when suddenly bub-bub-bub-bub-bub-brrrrr, from a little square wood fifty yards to our right, a heap of rifle-shooting. At us, if you please. They had let the scouts go and return, and were trying to demolish the thirty. We chucked ourselves flat and slipped into some empty trenches which very conveniently happened to be there. That wood was thick with Germans, who had no right to be there, quite on our side of the battle-field.

George volunteered to fetch help from the regiments behind to clear the wood. He ‘hopped out and ran like a hare’. However, the English and Scots troops he encountered would do nothing, because they were ‘tired out and their nerves shattered by perpetual shell-fire, Black Marias, shrapnel and machine-guns’. George therefore hared off again, almost completing a two-mile circle, when he came across a general and his staff ‘leaning over a five-barred gate’. He gave the general an ‘exact account’ of the front line he had come from, ‘with numbers, points of compass, names of regiments’.

The general told me that he was sure the wood had already been evacuated by the Germans, for a large body of men had gone forward while I was hunting round. So I slung my gun over my shoulder and went forward again over the fields […] towards the spot where I had left my C.O. and the thirty men. There were no shots flying over it; it was perfectly empty; there was not a human being in sight anywhere. When I was half-way across, pip, something whacked my left ankle and knocked me over. I simply, without any pause, rolled as fast as I could, like a rolling-pin and quite as blindly, and I hadn’t rolled over three times before I went pop into a nice newly-cut roadside trench, dug to carry the water off, 18 inches deep and wide.

More shots hit the road where he had first fallen. He ‘rammed’ his head back into the mud as far as possible and achieved complete cover. The time was about 3.30 p.m.

As he lay there, the fighting revved up, although the combatants were not at close quarters. ‘I was slap in the middle of the battle-field, snugly ensconced, but a little anxious. Shrapnel, rifle shots and machine-gun fire fizzed and pipped over my head. They rattled over my head and on the roadway; sometimes I thought they stirred my hair.’ Darkness fell at 5.30. Half an hour later he was found by ‘some delightfully tender-hearted English soldiers’, who carried him until he was met by stretcher-bearers. It was now raining heavily. At 7.30 they reached a farmhouse ‘just where yesterday’s sniper that we couldn’t find was sniping’ — and the sniper took shots at them in the dark. Here he was meant to be collected by a motor ambulance, but it was too dangerous for ambulances to come the extra mile. At 10.30, then, the Brigadier-General of 22nd Brigade, who George presumed was the one he had met that afternoon, sent his own car to drive George seven miles to a casualty clearing station. Obviously, this was well out of Ypres.

Whilst he had been lying in the mud, George had found that his wound ‘was not so very painful, about equal to toothache in the ankle’.

Some people have said to me that there is nothing unusual about this expression, but there is only one place that I have ever seen anything like it in print. On 14 May 1890 O.S. Chekhov wrote to his family on his journey to Sakhalin that he had been attacked by ‘acute toothache in my heels’ (he feared it was frostbite). The letter was published in 1907 in one of the symposia about Chekhov that were being brought out then and which Calderon was assiduously reading. It seems to me quite possible, therefore, that George’s expression is a reminiscence of Chekhov’s.

Next entry: 30 October 1914