Calderonia is an experiment in biography through a blog. It tells the story of George and Kittie Calderon’s lives from 30 July 1914 to 30 July 1915 from day to day as it happened, but exactly 100 years afterwards. It therefore feels like a biography in real time. When no facts were known for a particular day, the author posted on subjects ranging from the Edwardians, recently published biographies and his own problems as a biographer, to translating Chekhov and the Commemoration of World War I.

The blog-biography can be accessed in various ways. To read it from the beginning, go to the top of the column on the right and click the appropriate link. You can then read forward in time by clicking the link at the end of each post. If you wish to start at a particular month, scroll down the column on the right to Archive at the bottom. Posts can also be selected through Search Calderonia and the Tags on the right. An update on the complete biography of George Calderon always follows this introduction.

24/2/16. Local historians are the salt of the earth. They know their specialist area intimately and utterly. When the subjects of biographies settle for significant periods of time in different places, as George did at Eastcote, George and Kittie did at Hampstead, then Kittie did at Sheet and Kennington, without the help of local historians biographers would only scratch the surface of their lives in these places.

In the case of Eastcote, I was unbelievably lucky, because Karen Spink had already researched and published a terrific article about George’s time there (1898-1900) for the 1999 issue of the Journal of Ruislip, Northwood and Eastcote Local History Society (RNELHS). Karen twice walked me through the mile and a half of footpaths and road that George would have taken on his bicycle to get from his digs at Eastcote to catch the train at Pinner station on his way to the British Museum. She also showed me all over historic Eastcote and arranged for me to visit the private property where George lived. This is not to mention the endless sources she sent me about the life of Eastcote in those years. If my very large chapter two, ‘Eastcote Man’, has any deep texture apart from George’s love letters written from Eastcote to Kittie, it is entirely thanks to Karen, who also independently undertook to research the Calderons’ property in Hampstead.

Sheila Ayres of Camden History Society then helped Karen and me arrange a visit to two of the three private properties that once made up George and Kittie’s house in Hampstead. This was fascinating, as we had Kittie’s photograph album of 1902 to accompany us. The present owners were most welcoming and enthusiastic about the project.

My point about these wonderful local historians is not that they have spared me months and months of researching Eastcote and Hampstead that I would, of course, have been obliged to do myself, it is that I could never match their knowledge of these places and they have allowed me access to it with truly humbling generosity.

At Sheet in Hampshire a chance encounter led me to Vaughan Clarke, an historian who through his local contacts was able to confirm that the house I thought was where Kittie had lived 1922-34 was indeed ‘Kay’s Crib’ until its name was changed seventy years ago. Mr Clarke was also able to enlighten me about the social stratification of Sheet in the 1920s; this proved critical for working out why Kittie failed to ‘settle’ there. Mr Clarke is now Chairman of Petersfield Museum, which is well worth a visit. Each year the gallery of the museum exhibits a different selection of the painter Flora Twort (1893-1985), whom Kittie probably knew and who moved from Hampstead to Petersfield before her.

I have visited Kennington several times, and four years ago I placed appeals in local papers for anyone who still remembered Kittie to contact me (no-one did). For my last chapter, completed a month ago, I needed to get a feel for — to know as much as possible about –the life going on in Kennington outside Kittie’s windows at ‘White Raven’, where she lived from 1934 to 1948. I had over a hundred letters that she received in that period, about a dozen of her own, and many documents, but I needed as much context as possible. Here, the Ashford Archaeological and Historical Society have come to the rescue. Not only have they put feelers out amongst the senior population of Kennington, they are writing a piece about Kittie themselves for the Kentish Express. Amongst other things, this may settle the question of whether, as I think, The Cherry Orchard in George’s translation was performed at Ashford in 1940/41 as part of a campaign to raise money for the war effort.

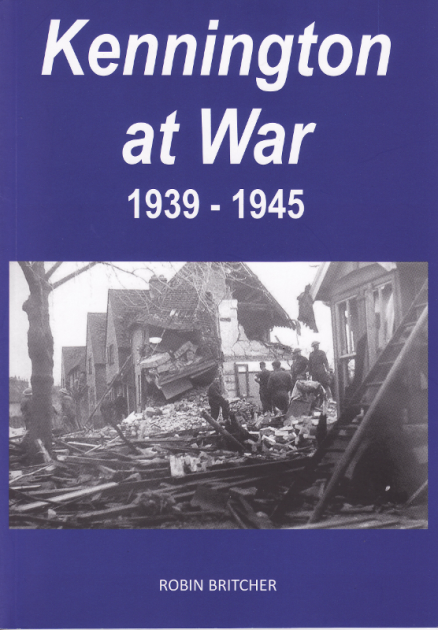

But above all, Robin Britcher, a member of the Ashford Archaeological and Historical Society, has spent ten years researching life at Kennington during World War 2, the result of which is this superb little book, published last month:

This book has provided absolutely critical local context to Kittie’s and Elizabeth’s lives at ‘White Raven’ during the war. Kittie wrote to Percy Lubbock in Montreux about every ten days and it is possible she mentioned to him some of the drama that was going on around her at Kennington, but maybe wartime censorship prevented her, and in any case her letters have not survived. Without Robin Britcher’s book, then, I would never have known that Kittie’s next-door neighbours were interned as enemy aliens, their house became a military nerve centre, a Heinkel bomber came down only a few hundred yards from ‘White Raven’, seventeen residents of Kennington died on active service, and nine bombs were dropped on the village killing two people, injuring others and wrecking homes. Kittie’s polite refusal of offers to accommodate her for the duration in places as far afield as Fife and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, takes on an even grittier edge.

However, Robin Britcher’s book is not only a portrait of Kennington during the war, it is an in-depth portrait of the village’s life as such: there is so much in it about the workings and personalities of the village that its usefulness for me extends beyond the war years. It is also very attractively presented, with masses of illustrations and an extremely well written text. I warmly recommend it. It can be bought directly from Mr Britcher at 169 Faversham Road, Kennington, Ashford, Kent TN24 9AE, by sending a cheque for £6.50 (includes postage and packing) made out to Robin Britcher.

I cannot help thinking that this country may have the best local historians in the world.

By the end of this week I shall have revised/rewritten about 58% of my biography of George. I have ‘lost’ a week because of the need to write a few new sections, particularly in the light of the sensational discovery last year of George’s pocket diary for 1907 — the only diary of his known.

This is the most recent ‘Watch this Space’ post. For the archive of ‘Watch this Space’, please click here.

Related

Watch this Space

Calderonia is an experiment in biography through a blog. It tells the story of George and Kittie Calderon’s lives from 30 July 1914 to 30 July 1915 from day to day as it happened, but exactly 100 years afterwards. It therefore feels like a biography in real time. When no facts were known for a particular day, the author posted on subjects ranging from the Edwardians, recently published biographies and his own problems as a biographer, to translating Chekhov and the Commemoration of World War I.

The blog-biography can be accessed in various ways. To read it from the beginning, go to the top of the column on the right and click the appropriate link. You can then read forward in time by clicking the link at the end of each post. If you wish to start at a particular month, scroll down the column on the right to Archive at the bottom. Posts can also be selected through Search Calderonia and the Tags on the right. An update on the complete biography of George Calderon always follows this introduction.

24/2/16. Local historians are the salt of the earth. They know their specialist area intimately and utterly. When the subjects of biographies settle for significant periods of time in different places, as George did at Eastcote, George and Kittie did at Hampstead, then Kittie did at Sheet and Kennington, without the help of local historians biographers would only scratch the surface of their lives in these places.

In the case of Eastcote, I was unbelievably lucky, because Karen Spink had already researched and published a terrific article about George’s time there (1898-1900) for the 1999 issue of the Journal of Ruislip, Northwood and Eastcote Local History Society (RNELHS). Karen twice walked me through the mile and a half of footpaths and road that George would have taken on his bicycle to get from his digs at Eastcote to catch the train at Pinner station on his way to the British Museum. She also showed me all over historic Eastcote and arranged for me to visit the private property where George lived. This is not to mention the endless sources she sent me about the life of Eastcote in those years. If my very large chapter two, ‘Eastcote Man’, has any deep texture apart from George’s love letters written from Eastcote to Kittie, it is entirely thanks to Karen, who also independently undertook to research the Calderons’ property in Hampstead.

Sheila Ayres of Camden History Society then helped Karen and me arrange a visit to two of the three private properties that once made up George and Kittie’s house in Hampstead. This was fascinating, as we had Kittie’s photograph album of 1902 to accompany us. The present owners were most welcoming and enthusiastic about the project.

My point about these wonderful local historians is not that they have spared me months and months of researching Eastcote and Hampstead that I would, of course, have been obliged to do myself, it is that I could never match their knowledge of these places and they have allowed me access to it with truly humbling generosity.

At Sheet in Hampshire a chance encounter led me to Vaughan Clarke, an historian who through his local contacts was able to confirm that the house I thought was where Kittie had lived 1922-34 was indeed ‘Kay’s Crib’ until its name was changed seventy years ago. Mr Clarke was also able to enlighten me about the social stratification of Sheet in the 1920s; this proved critical for working out why Kittie failed to ‘settle’ there. Mr Clarke is now Chairman of Petersfield Museum, which is well worth a visit. Each year the gallery of the museum exhibits a different selection of the painter Flora Twort (1893-1985), whom Kittie probably knew and who moved from Hampstead to Petersfield before her.

I have visited Kennington several times, and four years ago I placed appeals in local papers for anyone who still remembered Kittie to contact me (no-one did). For my last chapter, completed a month ago, I needed to get a feel for — to know as much as possible about –the life going on in Kennington outside Kittie’s windows at ‘White Raven’, where she lived from 1934 to 1948. I had over a hundred letters that she received in that period, about a dozen of her own, and many documents, but I needed as much context as possible. Here, the Ashford Archaeological and Historical Society have come to the rescue. Not only have they put feelers out amongst the senior population of Kennington, they are writing a piece about Kittie themselves for the Kentish Express. Amongst other things, this may settle the question of whether, as I think, The Cherry Orchard in George’s translation was performed at Ashford in 1940/41 as part of a campaign to raise money for the war effort.

But above all, Robin Britcher, a member of the Ashford Archaeological and Historical Society, has spent ten years researching life at Kennington during World War 2, the result of which is this superb little book, published last month:

This book has provided absolutely critical local context to Kittie’s and Elizabeth’s lives at ‘White Raven’ during the war. Kittie wrote to Percy Lubbock in Montreux about every ten days and it is possible she mentioned to him some of the drama that was going on around her at Kennington, but maybe wartime censorship prevented her, and in any case her letters have not survived. Without Robin Britcher’s book, then, I would never have known that Kittie’s next-door neighbours were interned as enemy aliens, their house became a military nerve centre, a Heinkel bomber came down only a few hundred yards from ‘White Raven’, seventeen residents of Kennington died on active service, and nine bombs were dropped on the village killing two people, injuring others and wrecking homes. Kittie’s polite refusal of offers to accommodate her for the duration in places as far afield as Fife and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, takes on an even grittier edge.

However, Robin Britcher’s book is not only a portrait of Kennington during the war, it is an in-depth portrait of the village’s life as such: there is so much in it about the workings and personalities of the village that its usefulness for me extends beyond the war years. It is also very attractively presented, with masses of illustrations and an extremely well written text. I warmly recommend it. It can be bought directly from Mr Britcher at 169 Faversham Road, Kennington, Ashford, Kent TN24 9AE, by sending a cheque for £6.50 (includes postage and packing) made out to Robin Britcher.

I cannot help thinking that this country may have the best local historians in the world.

By the end of this week I shall have revised/rewritten about 58% of my biography of George. I have ‘lost’ a week because of the need to write a few new sections, particularly in the light of the sensational discovery last year of George’s pocket diary for 1907 — the only diary of his known.

This is the most recent ‘Watch this Space’ post. For the archive of ‘Watch this Space’, please click here.

Share this:

Related