It does not seem exactly a year since the small boys Jack and Roly Pym ran across from their holiday home at Seaview on the Isle of Wight to greet George Calderon, a kind of uncle to them, who had just arrived to take a room in the villa opposite…

It seems an eternity.

It seems an eternity because so much has happened in only one year: from the declaration of war on Germany five days later, through George’s protracted efforts to get to the Front, through his experiences at Ypres, his recovery from a wound, through illness and long weeks away from home, to jockeying himself into a position from which he could be sent to the most dangerous spot on another Front… Then there were the enclosing events of this unspeakable War, both abroad and on the home front, George’s family life, his ongoing literary projects, the lives of his and Kittie’s many friends, the problems of national commemoration today, the trials of biographers… And finally sudden death at Gallipoli and no closure in sight for Kittie.

Both for me and, I know, some followers, it also seems an eternity because we have lived through it all day by day. Somewhere, I believe, Carl Jung said that the present is ‘terrible in the intensity of its ambivalence’. Rather like one’s own life, so many of the days of this blog have been intense with that ambivalence that I can no longer remember them all; the relevant brain cells have apparently been seared out; I cannot possibly now get my memory round the whole of this blog-year’s events.

The experience has, yes, been a bit wearing. I am a bit ‘gutted’. Whether this is just the exhaustion of ‘experiencing’ all this with George and Kittie, or whether it is some kind of cathartic ‘gutting’, I can’t say. There is much to digest from running this blog for a year, and I will need time to do that. I daresay others will, too.

Only three things remain:

First, to thank my son Jim Miles from the bottom of my heart for designing, running, and constantly improving this blog, then fixing at a moment’s notice the kind of occasional emergency that we seemed faced with on Monday morning (27 July). I would never have ‘got up and done’ this blog without my wife’s and son’s initiative, and it would simply have been impossible without their input for more than a year. Similarly, I am fundamentally beholden to the encouragement, advice and assistance of Mr Johnnie Pym, who is a famously meticulous editor and as the son of the aforementioned Jack Pym stands closer to George, Kittie and the world of Foxwold than anyone. The trustees of the Calderon estate and Johnnie Pym have with immense generosity allowed me to post any document or photograph in which they hold copyright. I cannot thank them enough. My thanks to my brilliant research assistant Mike Welch, who has followed up so many leads for me in databases and national archives, also know no bounds. I owe a special debt of gratitude to those worldwide, particularly Clare Hopkins, Louisa Scherchen, Katy George, Johnnie Pym, John Dewey, Derwent May, James Muckle, Harvey Pitcher, Sam Evans and Peter Hart, who have responded to posts with such stimulating Comments or emails.

Second, to explain that the blog will continue to be available online in its entirety. It will in effect become a website about George and Kittie’s lives 1914-15, and in the fullness of time special links will be put in to enhance its use as a database. Some editing will probably take place, and some new material be added to existing posts. The narrative ends today, but from tomorrow, 31 July 2015, there will always be a last post entitled ‘Watch this Space’, which will introduce new visitors to the site and contain the latest news on the writing and publication of the full biography George Calderon: Edwardian Genius. Comments will be responded to/moderated once a week.

Third, to summarise the rest of Kittie’s life without George.

* * *

‘White Raven’

On 9 September 1915 Kittie received her last telegram from the War Office. It told her that George was ‘now unofficially believed killed in action 4th June and Lord Kitchener expresses his sympathy’. She continued to live by the hope that he was a prisoner in Turkey, but in May 1919 the last prisoners were returned from Turkish captivity and George was not among them. Nevertheless, she insisted that his name always be kept on the list of ‘Missing’. She told her god-daughter, Lesbia Corbet, that she seriously expected George to ‘walk in the door one day’, just as he had in 1906 after months in the Pacific.

Kittie now threw herself into editing a collection of George’s works and assisting Percy Lubbock in his biography-tribute George Calderon: A Sketch from Memory. These five books were published by Grant Richards between 1921 and 1924. All were very well received, especially Tahiti (which Kittie had assembled from George’s drafts and notes) and Percy’s memoir. During those years, the national press was speckled with reviews of George’s works, memories of him, and attempts to evaluate his life achievement. Some of his plays were reprinted as single works, his Chekhov translations and introduction were reprinted in Britain and America, there were stage and radio productions of his plays, and J.B. Fagan’s 1925 production of The Cherry Orchard in George’s translation finally established Chekhov in the commercial theatre.

On 5 August 1921 the third great love of Kittie’s life, Nina Corbet (‘Black Raven’), died suddenly in Italy. Many of Kittie’s friends (e.g. Masefield and the Sturge Moores) had already left London, and a year later she settled with her faithful housekeeper Elizabeth Ellis in a cottage at Sheet, near Petersfield, in Hampshire. Probably she was attracted by the Arts and Crafts group there and the proximity of a branch of the Lubbock family. However, the petty politics of this rather self-fancying community did not suit her. She spent much time away from Sheet staying with friends, then in 1934 moved to ‘White Raven’, a house specially built for her by architect Jack Pym near Ashford, Kent. Here she was close to her brother, John Pakenham Hamilton, and could regularly visit the Pyms at Foxwold. She turned the green field in which ‘White Raven’ was set into a superb garden. She was happy there.

As well as taking an active part in church life and voluntary organisations at Ashford, Kittie received visits at ‘White Raven’ from many old friends, including, probably, Laurence Binyon, and was always available to her numerous godchildren. She often spent the nights weeding her own and George’s archives, captioning photographs and writing comments on letters, as well as composing fragments of memoir herself. Her sight was failing, however, and she was assailed by nameless health problems. In 1939 she revisited her birthplace at St Ernan’s, Donegal, with her friend Louise Rosales.

The Second World War was extremely stressful for Kittie, as the railway yards of Ashford were a bombing target and ‘White Raven’ was directly under the flight path of doodlebugs. On 1 November 1944 Kittie and Elizabeth Ellis narrowly escaped death when a flying bomb landed at the bottom of the garden and blew in the roof of ‘White Raven’. After the War her health deteriorated rapidly. In 1948 she moved with Ellis to Hove, close to her lifelong friend Kathleen Skipwith. Then Kittie went into a nursing home in Brighton, where she died on 30 January 1950 in her eighty-third year.

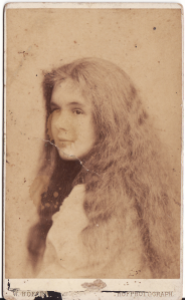

‘Dear grandmother, you are younger these days than you were; that expression in yr veiled eyes, tender and half ironical in look, is the expression of yr girlhood, the days of the miniature and the hanging locks; the tiny smile, the little look of bliss — these are spring buds coming out again with the new year of love. There are rich individual tones in yr voice.’ (George Calderon to Katharine Ripley, 31 January 1899)

I expected to feel sad when this blog ended. But now the last day has come and I find the feeling is more akin to finishing a book that was so absorbing I wanted never to get to the final page. As with the closing of such a book, I am left with a sense of satisfaction and understanding, and pleasure that I have the option to read it again, and at a different speed.

Thank you for the tremendous amount of work you have put into this project. Calderonia has been unfailingly interesting and extraordinarily stimulating. It has also been at times painful, frustrating, and exhilarating. George has been regularly infuriating and Kittie, occasionally, exasperating. Other modifiers come to mind with regard to the Gallipoli campaign, and to the mores of our Edwardian forebears. In short, it has been a wonderful privilege to have had this unrestricted entree into the lives of such a remarkable couple at such a momentous time.

A year ago, all I knew about George Calderon was that he was the oldest graduate of Trinity College to fall in action in World War One. That tag gave him a tragic aura which resonated poignantly with many college members. Now I am aware of his tremendous energy and the richness of his life – indeed, his genius – and a more genuine and nuanced feeling of sadness comes from a deeper appreciation of his sacrifice. As you regularly remind us, ‘empathy has to be intelligent, critical….’ And now it can be.

I am sure I am not alone in feeling especially sad for Kittie in her long and dwindling widowhood. Thank you for finishing with this beautiful expression of George’s love for her. Are these words written in his hand on the back of her childhood photograph? Could we see that too?

There is a type of memorabilia that is regularly to be found amidst the remembrance of World War One: the sudden and apparently random token, or the small and inconsequential fact that combines with one’s awareness of a fallen soldier’s fate to evoke an unexpected surge of intense emotion. The response might be triggered by a line in a letter or an article retrieved from a dead man’s pocket; in the case of Jim Corbet it was the knowledge that his sister already had her frock for his wedding. It is such little details that, if we are susceptible, are most likely to make us cry. Books and documentaries that use killer storms and natural disasters for the purpose of entertainment are sometimes categorised as ‘weather porn’ and ‘disaster porn’; and following from these, I have come to think of this genre of commemorative material as ‘war porn’. To be moved by something so intrinsically unimportant can feel like falling victim to a cheap and manipulative trick. The empathy engendered is powerful, sometimes pleasurable, and, I suspect, addictive. It is not however intelligent or critical…

Choosing to conclude your blog with this tourbillionesque glimpse into George and Kittie’s courtship could almost be an experiment in war porn! But no… This is a photograph that Kittie chose to keep with her in old age, unlike much of her correspondence that she destroyed. As such, it suggests a tentative answer to your final question. Was Kittie really in denial that George was dead? Did she refuse ever to acknowledge the accounts of the Third Battle of Krithia that were provided by eye-witnesses? With our modern day enthusiasm for ‘closure’, we might wish her to accept that George had gone; or, more positively, to recognise that the grief she suffered was in direct proportion to the love that they had shared. In other words, we want her to be strong, realistic, sensible. But maybe there is another scenario. When Kittie told her goddaughter Lesbia that she ‘expected [George] to walk through the door one day’, was she just sharing a comforting fantasy, an exercise in imagination and memory that sustained her for 35 years without him at her side?

Your stamina as a Commenter, Clare, is astounding — and as ever I am highly appreciative. Thank you particularly for what you say about ‘Calderonia’ resembling a book, which you have ‘the option to read again, and at a different speed’. This is an extremely gratifying and unexpected development in a ‘mere blog’ (as I started by regarding it). I know that several stalwarts are re-reading it, and I must say the daily numbers of presumably new viewers of the ‘website’ are surprising. You must take the credit for regularly kicking the Comment ball into play from the beginning, and you will always be welcome to leave Comments in future, e.g. about why you found George ‘regularly infuriating’ and even Kittie ‘occasionally exasperating’!

I was hoping that the concept of ‘war porn’ that you have coined in this latest would attract a shower of Comments, but perhaps there are still too many taboos surrounding commemoration of WW1 even to air this subject? Personally, though, I find the concept of ‘war porn’, as you have defined and discussed it, perfectly legitimate and useful. Many of us feel that as a nation we are walking a knife edge these days between empathy and sentiment in our commemoration of historical events, especially WW1. If the kind of memorabilia or facts you refer to are provided in order to tick the box ‘Make people cry’, then of course this is manipulative. ‘Porn’ is certainly applicable to this kind of exploitation. We need to be empathetic to real events of the past, we must be empathetic, but our empathy needs to be at the service of our understanding, i.e. philosophically ‘heuristic’. I fear we are losing the ability/training/desire to focus the ‘unexpected surge of intense emotion’ on the intrinsic significance of what we see, and I think we need to learn to do this or we WILL be manipulated… I’m not against these highly emotional tokens or biographical features, then, even when they are blatantly manipulative, because it must come down to how, rationally, we ourselves respond to them. On the other hand, there are some that are so powerful I don’t know what to say. For example, a mere photograph of a bin of tumbled stripped shoes of the murdered at Auschwitz leaves me incoherent — so much so that I know I could never visit the place itself. Could such an image ever become ‘manipulative’?

Naturally, I am very glad that you don’t find my concluding image on 30 July an ‘experiment in war porn’! If I attempt to be objective towards myself, I must admit that my use of the image plus quotation from George’s letter is manipulative in the sense that I wanted to leave followers with a juxtaposition of image and words that might be emotionally powerful. But, of course, the context I intended was not that of the War, or even ‘Calderonia’, but the lives of these two people as a whole, outside 1914-15. I also wanted to reassert the focus on both George and Kittie, after George was killed on 4 June and the rest of the blog was largely about Kittie the survivor. No, George’s words are not written on the back of the photograph of Kittie aged eighteen, they are taken from his letter to her of January 1899 (she had been going on about her grey hair and how much older she was than George, etc). But I would put my money on ‘the miniature’ that George refers to being this particular photograph.

As for your final questions, e.g. ‘Was Kittie really in denial that George was dead?’, they are very perceptive as always, but I am going to leave them rhetorical… As it happens, my reading of post-blog documents in the past week has revealed that in 1919 she was capable of telling the War Office one month that she accepted George was dead, and telling them the next month still to consider him a prisoner.

Can there ever be a last word on the subject of commemoration? We are fortunate that we can choose whether to visit Auschwitz or not; but if we do, I see nothing wrong in being incoherent. Like the Helles Memorial, it is a truly aweful (sic) place – how can we find the thoughts let alone the words to express what we feel? To go to the specific site where so many – or where one particular individual – died can be akin to a pilgrimage: a positive demonstration that we care; a declaration of intent to remember them; a willingness to be humbled by the experience. To stand in numb or anguished silence seems an entirely appropriate act of commemoration. Perhaps that is why, almost a century after the guns ceased firing on the Western Front, the Two Minutes Silence remains so potent on Remembrance Day.

I have hesitated whether to take the bait and answer your question to me… But go on then, why did I find George Calderon so ‘regularly infuriating’? This answer is from memory – my impressions formed from a daily read of Calderonia – and I apologise in advance if I am vague and/or inaccurate.

I found George’s whole attitude to the War rather arrogant. He seemed to think that because he wanted to be an army officer, he therefore had the right to be one; as if the selection criteria just did not apply to him. What happened in Flanders suggests that the military authorities were in fact right. As a man in his mid-40s George probably was too old to cope with the strenuous demands of the front line. He had health problems caused – the doctor suggested – by being too long in the saddle. Whatever the underlying medical issues, age surely affected his ability to recover from the unaccustomed hours of riding. A man with greater humility might have revised his plans. I can’t recall any occasion when George took another person’s advice.

Secondly, I found George selfish. Not because he ignored Kittie’s pleas to stay at home – that was a matter between the two of them and his conscience/sense of duty. But one example of his selfishness with regard to Kittie was that he did not let her set up house for him when he was at officer training camp. He wanted the full experience of an officer’s life for himself – but he denied her the full experience of an officer’s wife. And then – good grief – he wrote home about the pleasure of visiting the other officers’ wives who were there!

I can’t think of any behaviour on George’s part that I could describe as unselfish. (His final act of self-sacrifice, obviously, is in a different league.) George’s whole interaction with the War was about himself. I have read letters home from various other junior officers, and quite a few tributes to the fallen, and one common feature is how deeply most lieutenants cared about ‘their’ men: learning their names, taking time to show an interest in their lives, valuing their skills and qualities. George’s letters were much more about himself, his experiences, his surroundings. I know he was only with the KOSB for an extremely short time, but comments in his letters suggest that he saw his men not as individuals but as types. I recall that once he got something or other for his platoon, but the story read as his own triumph over the army system. On another occasion he wrote about censoring soldiers’ letters – but almost as if the men he led were comic characters in a play, not real people with whom he could have engaged on a personal level.

And finally I was shocked and, I have to admit, disappointed, when I learned that George campaigned so aggressively against female suffrage.

Readers, no doubt you are thinking how harsh, judgemental, and opinionated I am. My sincere apologies if I have offended you by this attempt to describe one aspect of my personal response to a year of George Calderon’s life. I am fully aware that I have subjected an Edwardian character to 21st-century scrutiny. This may be unfair, but on the other hand it is exactly what Patrick has invited us to do by laying out George and Kittie’s daily lives as he has. I could equally say how fond I became of George, and how much I liked and admired many other facets of his character – his sense of humour, his determination, his enthusiasm, his copious letter writing, his feistiness, his carpe diem attitude, his Christmas dinner invitation to his mother-in-law, the way he took responsibility for his own actions, his interest in knitting. At times I wondered if beneath the veneer of Edwardian manners he could actually be quite nasty – and I found that endearingly human. He was a complex man, and enormously courageous. As his college friend Laurence Binyon said,

He went to the very end;

He counted not the cost;

What he believed, he did.

And now it’s my turn to ask a question. Back on 4 June, Patrick, you said that George got as far as he did towards the Turkish trench because of ‘his very superior running skills’. This phrase has lodged uneasily in my mind ever since. Another member of Trinity College who has been commemorated in the past year is the Olympic athlete Gerard “Twiggy” Anderson who fell, sword in hand, leading a bayonet charge near Hooge on 9 November 1914. He was 25. Four years earlier Twiggy had set a World Record for the 400 yards hurdles that was not broken for 16 years. Superior running skills (like swords) are no defence against bullets. But George was 46, his working life was largely sedentary, he had only recently recovered from a wound which had reduced his mobility for some time, and following that he had been laid low by flu. His wife believed he was unwell; you have hinted that you suspect he was seriously ill. Did Percy Lubbock tell you that George had superior running skills? Is this detail, in fact, part of a myth?

Fortunate indeed is any writer who has a Socratic ‘gadfly’ that can provoke him/her into looking at his/her subject from an entirely different angle – into re-viewing it. He/she probably won’t think they are fortunate (like horses, they may actually feel driven mad by it!), but they are. For when you have been working on a book for a few years you have almost certainly developed a form of tunnel vision and the best thing that can happen to you is to be brought out of that tunnel.

As I have before, then, I thank Clare Hopkins, Archivist of Trinity College, Oxford, where George Calderon was an undergraduate, from the bottom of my heart for taking time to present such a rigorously argued ‘anti-view’ of George in her latest Comment. It has made me think, it has made me swivel my head owl-like to see things from a diametrically opposed viewpoint, and that’s undoubtedly good for me. Clare posted her Comment on 14 August, so it’s high time I responded.

I must confess that I hadn’t thought of it, but Clare is right: George’s attitude to the War can look arrogant, and he did seem to think that ‘because he wanted to be an army officer, he therefore had the right to be one; as if the selection criteria did not apply to him’. That is irrefutably evidenced by Percy Lubbock’s remark in his Obituary of George (The Times, 5 May 1919) that ‘even before the declaration of war’ George ‘genially and resolutely insisted’ on being given a commission. As Clare says, he thought he had a right to one.

But this is a prime example of where one must understand the times in which a biographical subject lived. In Edwardian terms, George did have a right to a commission! Even I (I freely admit) have occasionally overlooked the visceral acceptance of ‘class’ in Edwardian society. To be an officer, you had to be a gent. There were, of course, some people who rose from the ranks, but I have read in numerous places that they were pretty rare. If you were a gent, you automatically qualified to train to be an officer; if you weren’t a gent, the highest rank you were likely to attain was sergeant-major. So as a Rugbeian, Oxfordian, qualified barrister and property-owner, George Calderon could ‘insist’ on being given a commission – especially as he had served a decent term in the Artists’ Corps and Inns of Court Volunteers.

Yet if one must always strive to understand one’s man in the context of his times (this applies pre-eminently to George’s views on suffragettes), Clare is absolutely right that ‘by laying out George and Kittie’s daily lives’ as I did in my blog I have ‘invited’ readers to ‘subject an Edwardian character to 21st-century scrutiny’. Again, thank you for saying that, Clare, and for expressing it so clearly. Because this, surely, is the other thing biographies are ‘about’. We read them to understand a person and his/her times, but also, perhaps above all, to interact with them, question them, dialogize with them, comment on them, argue with them, and, naturally, judge them – and all that from our own point of view in time. There is nothing ‘harsh, judgemental, and opinionated’, therefore, about Clare’s view of George, because if a biography doesn’t provoke its readers it hasn’t lived.

Yes, ‘as a man in his mid-40s George probably was too old to cope with the strenuous demands of the front line’. I think that by the time he reached Gallipoli he was chronically exhausted. But we know why he sacrificed himself in this way (as Clare acknowledges)… Or do we? Clare’s hilarious observation ‘I can’t recall any occasion when George took another person’s advice’ is correct, so is her charge that George was ‘selfish’. But that is what writers are like. The whole of the rest of the world will dissuade you from being a writer if you let it. I am deeply convinced that George was impelled to the war fronts because he would write about his experiences there, and no-one was going to stop him. Half-consciously perhaps, it was a project rather like his trip to Tahiti, and if he had survived I think there is every chance his war book would have been as good.

So writers are selfish…about their writing, because that’s what they ‘do’.

If, again, we look at his treatment of Kittie from a 2015 point of view, as Clare has so rightly and sanely invited us to do, one example of George’s selfishness would be that he ‘denied her the full experience of an officer’s wife’ by not letting her set up house for him in Brockhurst like other officers’ wives. And, I agree, from where we live it seems outrageous that he then ‘wrote home about the pleasure of visiting the other officers’ wives who were there!’. There is no real evidence, however, that Kittie wanted to set up a home in Brockhurst (and be separated from Nina Corbet). On the contrary, where George’s six-month trip to the South Seas was concerned, Kittie felt he should go on his own because, as she put it in her memoirs, ‘a man can’t have completeness of adventure if he has got a woman with him’ – another Edwardian attitude we have to accept.

Since we ‘de-appled’ George’s letter of 10 May 1915 and discovered one woman (another officer’s wife?) was accusing him of being in love with another woman at Brockhurst, Helen Peel, it has emerged that both Kittie and George may have known the Peels already through their extensive Oxford contacts. A ‘Mrs Peel’ also features in Kittie’s address book, so perhaps they corresponded after George’s death. And, unpopular though this statement will certainly be, many writers on relationships have pointed out that ‘emotional infidelity’ is not ‘infidelity’.

Altogether, then, I do accept that in a sense George’s ‘whole interaction with the War was about himself’, as Clare puts it, because as well as the determination to defend his country and its values, he was driven to war by his desire for writerly adventure/experience, which is a profoundly individualistic (‘selfish’) desire. This explains why, indeed, his ‘letters were much more about himself, his experiences, his surroundings’, than his ‘men’. The letters were literally records of his experience that Kittie was to keep safe for when he came to write the book, as she had his letters, diaries and sketchbooks sent home in 1906 from Tahiti. This is why, as well as action, dialogue, humour and invective, they contain long literary descriptive paragraphs that to many have seemed out of place in ‘war letters’.

I agree that as a lieutenant he does not seem to have got close to or cared deeply about ‘his’ men. I think there are two factual explanations for this. First, as an interpreter with the ‘Blues’ he was attached to the top officers only – and there are plenty of descriptions of and anecdotes about those in his letters. But when he returned from Dunkirk and was sidelined by the Blues’ staff, he began ‘soldiering’ with privates and NCOs from the Royal Warwickshires as though he were one of their lieutenants, and Kittie wrote afterwards that he ‘really loved those men’. Unfortunately, of course, when he was made one of their officers and went into action with them, he was promptly wounded. Similarly, he couldn’t get to know his men well at Krithia because (a) there wasn’t time, (b) Sergeant Smith had been their effective leader until George arrived and Smith had been with them since the first landings, so the men still referred to it as ‘Sergeant Smith’s Platoon’.

I responded to Clare’s last question, regarding George’s ‘very superior running skills’, in a brief post on 16 August which I have since deleted for economy, so I will just summarise my position now. Yes, I think I overstated these ‘skills’. I accept that George, at 46, was no longer the fast sprinter he had been, especially after his leg wound at Ypres and considering his generally sapped condition. There is plenty of independent evidence that he had been a fast runner, though, and he himself claimed that he had run ‘like a hare’ and ‘at my best hundred-yard speed’ at Ypres. We now know that after the massacre of A Company on 4 June there was a slackening in the Turkish fire power. As Clare writes, ‘superior running skills (like swords) are no defence against bullets’. But a mathematician assures me that combined with the decrease in number of bullets, speed of running would be a factor in George and others in B Company getting about a hundred yards before they were either mown down or took cover in what is believed to have been a shallow ‘nullah’.

Again, my gratitude to Clare for her genuinely critical and unfailingly fruitful Comments all through the life of the blog knows no bounds. By common contemporary consent, George was a very complex man, and Clare has teased out some of the complexity that I missed!

It was remiss of me, in my last Comment, not to address the first paragraph of Clare Hopkins’s last Comment, which concerned commemoration. Clare began the paragraph by asking ‘Can there ever be a last word on the subject of commemoration?’ As new followers of the blog may ascertain by searching on ‘Commemoration’, we debated this subject over the year, with reference to World War I, a great deal.

I think it possible, therefore, that I subconsciously answered ‘no, there can’t be a last word on commemoration’, and moved on to address the questions that I have in my previous Comment to this one. Equally, back in August I was feeling ‘warred out’ and ‘commemorationed out’ and simply had nothing more to say. That situation has been changed by a visit that I made last weekend to the Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere in Hampshire, which was conceived and painted by Stanley Spencer.

In my own Comment of 6 August I said that the images and all that I know of Auschwitz and the Holocaust constrain me from visiting Auschwitz. I would be incoherent with emotion. The same is true for me of the Helles Memorial at Gallipoli or visiting the battlefield itself (to go to the spot where George Calderon was killed would be totally impossible). But Clare reasonably remarked that she saw ‘nothing wrong in being incoherent’ and that ‘to stand in numb or anguished silence’ at Helles or in Auschwitz ‘seems an entirely appropriate act of commemoration’.

Although I still know I couldn’t go to these places, I accept Clare’s view here. I have come to feel since August that the completely empathic response to such terrible events and individual sacrifice is ‘not enough’, in the sense that it’s only half of the act of commemoration. I’ve come round to this because of my personal experience that the subjective, holistic-empathic response reaches a limit where you have no more to give. Indeed you are exhausted, ‘gutted’ by it. Ceremony, ritual, more impersonal, rational and objective forms of commemoration, have to take over.

Another difficulty I have always had with memorials like Helles, Thiepval, or the daily ceremony at the Menin Gate, is their sheer scale. Certainly they create an awe-ful sense, but their size and architecture also seem uncomfortably ‘imperial’ — partaking even of the very gigantism and marmoreal impersonality that made World War I possible. Many people have said to me that the scale of and the silence at these memorials are what has made the deepest impression on them. I can’t help feeling, though, that I wouldn’t be able to get that experience from them myself with so many hundreds of other people present. There is an undeniable element of tourism at these memorials, even Auschwitz, which I have no ‘difficulty’ with but which I wouldn’t be able to stomach.

The reason I have no ‘difficulty’ with this commemorative tourism, or even with what Clare Hopkins aptly termed in her Comment of 30 July ‘war porn’, is that it surely does not matter how people are brought to a realisation of the horror of these events and, dare I say it, the sanctity of the victims, as long as they are brought to it. Of course the simply ‘educational’ value of a visit to such places is gold. And, as I say, the monument, war grave, ceremony, service or ritual seem to complete (close?) somewhat unemotionally an act that untrammeled empathy cannot.

But I have to say that Spencer’s nineteen frescoes in the Sandham Memorial Chapel are the most satisfying commemoration of World War I that I know. There are no corpses, gunfire, attacks and carnage in them, very few discernible weapons even, but the horror of 1914-18 warfare is the great Unspoken at the back of your mind as you study them. What the panels draw you into (and you could spend days discovering new things in them) is the most basic human life of the war, from scrubbing floors in hospitals, sorting the laundry, setting out kit for inspection, to scraping dead skin off frostbitten feet, buttering sandwiches in a hospital ward, map-reading or making a military road. All of the scenes are collective ones. As the excellent National Trust brochure puts it, they celebrate the ‘human companionship of war’. The sheer positiveness of this companionship — the fundamental humanity of the paintings — triumphs.

At the same time, Spencer’s personal and wonderfully modern christianity (the small letter seems appropriate) shines through everything, especially the vast altarpiece ‘Resurrection of the Soldiers’. In the centre of it are two mules waking from death and craning their necks round to look at the almost unnoticeable white figure of Christ in the mid-distance, to whom the resurrected soldiers are bringing their crosses. Apparently, Spencer believed that animals have souls and that is why he wasn’t invited to the consecration of the chapel by an Anglican bishop. It also explains why a soldier waking far right from his grave is touching two hilarious tortoises (the scene recalls Spencer’s war service in Greece and Macedonia), who presumably have also been resurrected.

It will take me ages, I think, to get my head round Spencer’s masterpiece (surely it is one of the greatest works of art of the twentieth century), but at the moment I would say that the reason I find it such a satisfying commemoration is that its celebration of common life, its astounding evocation of ‘ordinary’ men and women, is empathetically totally engaging, whilst his personal religious conception of the work provides ‘meaning’, a tentative, almost indefinable rational closure to the empathic. Spencer wrote of the altarpiece: ‘The truth that the cross is supposed to symbolise in this picture is that nothing is lost where a sacrifice has been the result of a perfect understanding.’ Not an exclusively Christian, or religious, truth, then; all can accept it as a moral and humanistic one.

Thank you for replying so comprehensively to my remarks about Commemoration. Just as psychologists have identified several distinct phases that people go through when a loved one dies, so I have come to think that there is a series of stages in the process of commemoration. The first is the ‘untrammelled empathy’ and the ‘subjective, holistic-empathic response’ that you describe. This happens at a personal level and we could call it Mourning; for many individuals it can last a lifetime. In this category are those elderly veterans of the Battle of Britain and D-Day who so moved the nation as they recalled their fallen comrades on our TV screens earlier this year. It seems to me that this is where you are with regard to George. As his biographer you have known him intimately; ‘alive’, he was a constant presence in your life, and now, very understandably, you are experiencing some of the emotions of the bereaved. I wonder if this is why you feel unable to stand in a crowd at Krithia – you would almost certainly be the only person there feeling that way.

Stage two of the commemorative process you have also identified: the ‘ceremony, ritual, more impersonal, rational and objective forms’ of cherishing the dead. This echoes the funerary rites that follow the death of any loved one. Done well, this stage is comforting because it provides reassurance that the deceased have value and deserve to be remembered. Let us call it Honouring. Examples of this stage include the crowds that lined the streets of Wootton Basset to greet the flag-draped coffins of soldiers killed in Afghanistan, the enumeration of names at Ground Zero on the anniversary of 9/11, and all local Armistice Day ceremonies. The emotions of Honouring encompass respect, reminiscence, and regret.

Stage three is a time of Memorialising – the creation or construction of something permanent that will outlast individual memory. After the funeral comes the gravestone, tree, or charity fund. Kittie Calderon threw herself into the production of books by, and about, George. The cover of Percy Lubbock’s A Sketch from Memory, you told us, is embossed in ‘real gold’, and certainly the motif still shines brightly on the copy in the Trinity College Library. I understand your distrust of the ‘imperial architecture’ of Great War cemeteries and memorials, and I sympathise with your objection to the ‘gigantism and marmoreal impersonality that made World War I possible’. On the other hand, the British Government had a choice. They could have followed the model of all previous European wars, dumping the bodies of private soldiers into anonymous pits, potentially to be used as fertiliser. After the Napoleonic and Crimean Wars, only officers could expect proper graves and inscriptions. But the insistence of the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the CWGC) that all ranks would be treated with equal respect and given identical memorials has always seemed to me a truly Great aspect of the War. This is the stage of commemoration when a soldier’s death is given meaning, and the emotions evolve into patriotic pride and gratitude. We appreciate what war memorials represent; we know that the fallen did their duty and gave their lives in the service of their country.

Stage four is when commemoration distils into History. Sooner or later memory and oral tradition fade away, to be replaced by facts known only from books or documentaries. You have identified this stage too, in the ‘educational’ visit to Auschwitz. The search for meaning in the deaths of the fallen is replaced by a thirst for knowledge of why and how wars happened. World War One seems easy to empathise with now, but it will all too soon slide away from future generations. As is already happening in Germany, the two World Wars seem destined to merge into a single historical event – with a short, failed peace in the middle, and outcomes that include the UN and the EU.

So where do art, music and literature fit into all of this? Artists and writers engage with every stage of commemoration. With regard to World War One, we might say that poets wrote to express their grief; ‘I vow to thee my country’ was composed to honour the fallen; Stanley Spencer created a lasting memorial to all combatants; while Sebastian Faulks’s Birdsong has lifted the work of tunnellers from complete obscurity to an esteemed place in history.

There is a fifth stage in the commemoration process, and I am tempted to call it Canonisation. I was fortunate last week to attend the ‘national homage’ to the Battle of Agincourt, celebrated at Westminster Abbey by an impressive array of establishment figures: the Duke of Kent, the Bishop of London, the Lord Mayors of London and Westminster, plus actors, academics, and aldermen. The choir and the organ music were magnificent, and the tomb of Henry V was revered. But what was the point of it all? How did one unexpected victory become the only battle of the Hundred Years War to be singled out for commemoration? We could argue that Agincourt is remembered solely because of Shakespeare’s rendition of it; certainly the programme would have been rather thin without those stirring scenes from Henry V. But it is more than that. Somewhere, somehow, consciously or subconsciously, Agincourt has come to exemplify important qualities in the English (or British) character – and its commemoration therefore serves to define and reinforce our national identity. Agincourt evokes admiration of an inspirational leader and identification with the plucky underdog – ‘we few, we happy few’. The Battle of Britain – ‘never was so much owed by so many, to so few’ – does exactly the same, and in the fullness of time it will surely achieve similar status in the commemorative canon of our staunch little island. But what part, if any, of World War One will make the cut? Its four grinding years are resonant with uneasy alliances, false starts, inconsistent leadership, frightful inventions, and terrible, terrible waste… I rather suspect, none of it.

I received several short email responses to Clare’s Comment of 2 November, and am therefore disappointed that no-one has actually posted a reply. I can only think this is because (a) people do broadly accept what Clare says, (b) therefore (or anyway) they don’t feel they have anything more to say about Commemoration.

It will not surprise you to learn, Clare, that the part of your Comment most vehemently disagreed with in emails and conversation with me was the last two sentences. Evidently, suspecting that ‘none of’ the ‘four grinding years’ of ‘uneasy alliances, false starts, inconsistent leadership, frightful inventions, and terrible, terrible waste’ would ‘make the cut in the commemorative canon of our staunch little island’ came too close for some people to saying that our sacrifice achieved nothing and we should never have joined the war. Most people do not now believe this. But your suspicion surely rightly reflects the unique difficulty of, as Reynolds put it yesterday, making our peace with WW1 and moving on. Is it perhaps possible that the ‘Great War’ will achieve a supreme status in the ‘commemorative canon’ as the exemplar of war’s ‘senseless’ waste even when that war was a just one?

Personally, I find your Comment a superb rationalisation of the whole subject. Thank you for taking so much trouble over it and expressing it so well. It would not surprise me if it is the last word about it on ‘Calderonia’, or at least if there were now a long pause. It certainly is a last word for me. I do broadly accept the process as you have brilliantly mapped it out and described it. I’m particularly grateful to you for suggesting that where I was with George at the time was in fact ‘mourning’ and ‘bereavement’…it seems perhaps fanciful with someone who is, as it were, merely a biographical creation, but I think you were right! I hope you will also be gratified to see how much your historical take on the issues overlaps with Reynolds’s.

One brief question after Reynolds’s lecture was: ‘Do you think that…well…just forgetting will bring us peace with the War?’ No, Reynolds replied, that’s not the answer — and you would presumably agree, Clare — what is needed is understanding. And I think that’s a very important point, because some people might take stage four in your commemorative process to mean simply ‘historicisation’, which they equate with draining the blood from, cerebralising and atrophying, i.e. something verging on forgetting.

Those of us who are not, and can never become, historians, fear the historicisation of the Great War like the devil. I do think the process of commemoration as you have traced it is very plausible, indeed probably right, but as someone who cannot think in purely historical terms I do not want the poets or the truth of WW1 to ‘lie down’. Indeed, I don’t think they can. A recent German President said that for the German nation there could be ‘no moral closure on the two world wars’. That does not apply to us because we did not cause those wars, but how as a nation will we ever get emotional closure as long as the poetry of Owen, say, Ivor Gurney, or Georg Trakl exists? Or the narratives of Graves, say, Brittain, or Erich Maria Remarque? Political and military events are ‘past’ in a way that art never is.

Attempting to stand back a little from what I have just written, I think I discern that my stance on the subject is as ‘nuanced’, meaning ambivalent, conflicted, paradoxical, as Reynolds’s was, and perhaps yours is too, Clare. We want closure and we don’t want closure. I hope you will not think me flippant if I conclude with Mrs Boffin’s words in Our Mutual Friend (Bk 2, Ch. 10): ‘It is, as Mr Rokesmith says, a matter of feeling, but Lor how many matters are a matter of feeling!’

What excellent advice, Patrick, ‘to stand back a little’ from this on-going discussion of commemoration. It is indeed difficult to maintain any sense of perspective when thinking about the horrors and losses of World War One. Thank you for your response to my latest comment, and for such an interesting summary of David Reynolds’ lecture. [See ‘Watch this Space’, 16 December 2015. PM]

I was sorry to learn that what I said previously may have annoyed some followers of Calderonia. I should have explained more clearly that my suggested stages of the commemorative process were only ever meant to be descriptive. And my prediction that World War One will come to be remembered only as history was no more than that – just me speculating about how future generations will see the conflict. I would be very glad to consider alternative conjectures, although I really don’t believe that anyone reading this in 2015 will live long enough to see whether we are right or wrong. I hope though that we all agree that it would be daft to expect future generations to engage with World War One exactly as we do. Consider the obsession with the Napoleonic Wars of, say, the Brontë sisters, and compare that with George’s light-hearted plan to celebrate the anniversary of Waterloo. If I am honest about my own position, I’m not sure ‘I feel enough about it’ – as you yourself once said about Agincourt – to bother to commemorate it at all. In 2015 we have a very restricted view of Waterloo, obscured as it is by two global and many lesser wars, and by two centuries of social change and technological advances. Many of us alive today feel a powerful connection with 1914–18 through the experiences of our grand- and great-grandparents; but by the time our grandchildren have become grandparents themselves, they will look back across a cultural and social landscape that will have been radically transformed by the War on Terror, or by catastrophic global warming, or by [Readers, please insert your own ideas here]. And if you will forgive my flippancy, our descendants may have a fixation not with Wilfred Owen or Ivor Gurney, but with great and resonant poetry that is yet to be written. ‘The last polar bear…’ anyone?

Perhaps others have emailed answers to your question as to whether ‘the “Great War” will achieve a supreme status in the “commemorative canon” as the exemplar of war’s “senseless” waste…’ As it happens, since posting my controversial suggestion that World War One would not achieve ‘stage five’, I have attended a lecture by Professor Anne Curry, who spoke at the Gwent Record Office about that supreme exemplar of canonisation, the Battle of Agincourt. Her expert view was that it has been remembered for purely political reasons – exhortatively rolled out by everyone from the Tudors to George Osborne. This has heartened me to stand by what I said: for why would any future national leader want to draw the attention of the electorate to negative images of the ‘senseless waste’ of a war that failed to achieve its goal – even if it was a just one?

I found your summary of David Reynolds’ explanation of why as a nation we are not at peace with World War One very helpful indeed. Where I take issue with him though is with the implication that we need to do something to achieve closure. My instinct is that Britain just needs to wait a bit – a lot – longer and the peace he hopes for will, eventually, descend. Again, it seems useful to compare commemoration with grieving. In one of your temporary posts you questioned whether the bereaved are harmed by being forced to accept closure before they are ready. Most people would agree that they are (pace George and his robust treatment of Kittie after Archie’s death. Here’s a new train of thought – did that interference make it harder for her to cope when she was widowed for the second time?) Where was I? Ah yes. Perhaps it is the very definition of closure that has caused the problem: immediately the achievement of it becomes pass/fail. It might be more helpful to see grieving as an open-ended and life-long process; this would for instance reduce social pressure on the families of murdered children to ‘move on’. Most but not all of us do manage to arrive at ‘acceptance’ of bereavement, but only after working through numerous stages – anger, denial, depression, bargaining, whatever – in our own time and order. Similarly, why should Britain compare itself with France or Germany as we collectively, and over many generations, come to terms with World War One?

Let’s hear it for historians! The Agincourt we feel we know is very different from the actual battle that Anne Curry reconstructed for her audience. I was to say the least startled by your remark that you ‘fear the historicisation of the Great War like the devil’! Given a choice between a patriotically sentimental view of World War One and a rigorous understanding of its causes and course, is not the latter better? But perhaps here too we should see the shift from memory to history as something fluid and on-going, with over-lapping stages which cannot be rushed and which will last for generations. On 3 July you said that the ‘process [of that commemorative staple, empathy] should be towards understanding’. And surely it is historians who with their impartial research and objective analysis can lead Britain towards that understanding – even if it does require us to ‘clamber out of the trenches and escape from poet’s corner’…

As I reflect further on ‘my’ stages of commemoration, it strikes me how long each one takes to run its course. Examples of present-day honouring and memorialising of World War One abound, while the flow of new histories shows no sign of abating. Here at Trinity College – George Calderon’s alma mater – we are actively remembering our fallen members, German as well as British, in a monthly display of their names alongside the earliest surviving manuscript of Laurence Binyon’s poem, ‘For the Fallen’. In April this year we unveiled a new memorial – to the College’s five fallen German and Austro-Hungarian members – in a very moving ceremony attended by the Austrian ambassador and the German chargé d’affaires. The impact of World War One on this small Oxford College was huge, and its effects are still being felt. The equivalent of more than three years’ intake of undergraduates was wiped out, while the 20th Century saw a surge of benefactions from their parents and others who found comfort in supporting an institution where the young men never did grow old, as they who were left grew old… At the risk of undermining my own argument, I have to confess that if ‘canonisation’ of World War One is going to happen anywhere, I think it will probably be here! I wonder what George Calderon would have made of that?

And as for our debate on this engrossing subject – will it really all be over by Christmas? Seasons Greetings, one and all!