Plan A for a commemoration of George’s death (see yesterday’s post) was really dictated by long accepted British forms of commemorative ritual. These have loosened up in recent years, of course, to a point where you have extended, all-singing-and-dancing customer-devised funerals and memorial services complete with video links to Australia, although an indulgent priest still presides. I actually think that the presence of a priest and a theological framework in which he/she sets death has a healthy restraining effect on the modern British tendency to secularised sentimentality — which is why I was pro plan A.

But we hadn’t asked ourselves what would have been most appropriate in the eyes of George and Kittie. As soon as I began to do this, I was struck by George’s words to Kittie in his letter of 10 May 1910: ‘Rejoice in the colour and vigour of the thing — and drink deep with jolly friends […] and other Rabelaisians. Your wishes for good, will work all the better when two or three of you are gathered together.’ Of course, the last nine words echo those of the Gospel, but it is characteristic that George is talking only of a secular, human impact of the ‘wishes for good’ shared between ‘two or three of you gathered together’.

The idea struck root, then, of a plan B that involved a very few people. After all, we could no longer accommodate scores because we no longer had the venue(s), so it had to be fewer rather than more. Then people started emailing from around Britain, from the EU, and from North America, to say they would ‘raise a glass’ to George on the day. The penny dropped that, in the 21st century, people could ‘commemorate’ anywhere on the globe, and at the same time, without being physically with you. And although we could no longer stage a ‘public’ commemoration, practically a memorial service, we could always stage one ‘in’ public: at Hampstead, near the very house that George and Kittie had lived in.

Reading the words ‘drink deep’ and ‘Rabelaisian’, I also suddenly remembered that George had referred in a letter to the ‘street café life’ of London that he liked so much. So a post-commemoration lunch in a restaurant that fitted that description seemed appropriate. Evidently he would have approved of it, Kittie probably too.

Mr John Pym, the grandson of the Calderons’ friends Violet and Evey Pym of Foxwold, and I, therefore went to Hampstead to reconnoitre and to sample a venue for the lunch. The space opposite the Calderons’ house was in fact ideal, and off the street, and Café Rouge on Hampstead High Street fitted George’s and our bill precisely. Where the invitees were concerned, at most a dozen could be accommodated on the verges of the public footpath, so the obvious candidates — the full available ‘Calderonia’ team plus spouses — were ideal, as they amounted to nine.

On 4 June, then, we nine assembled on the spot at 11.50, we read two pieces from Kittie’s memoirs and an officer’s diary relating to George’s departure for war and to the battle of 4 June 1915, we kept the two minutes’ silence at noon, then we read two verses from Laurence Binyon’s ode to George’s memory (see tomorrow’s post) and Nina Corbet’s letter of comfort to Kittie when George’s death was officially accepted in April 1919. Flowers were left, with a copy of the commemoration readings, for the owners of the former Calderon home, and we repaired to Café Rouge for a suitably Rabelaisian repast.

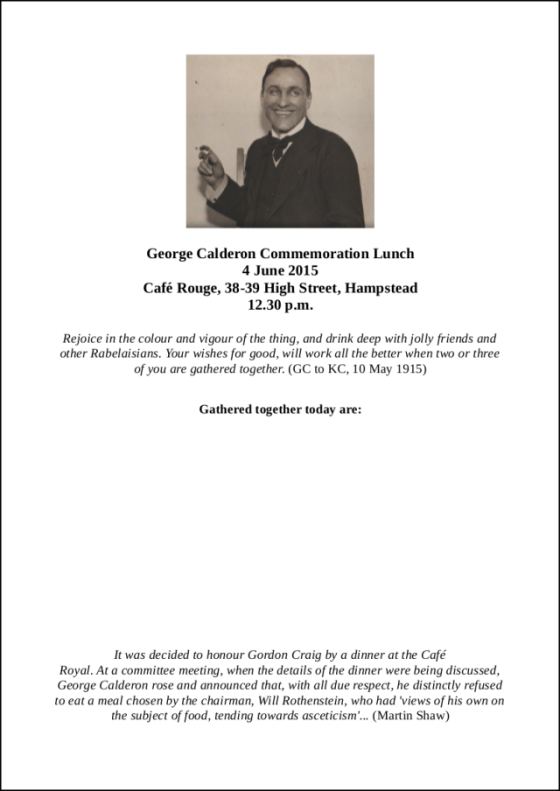

Over lunch the nine of us signed this commemorative programme (I can’t reproduce a signed copy, because of the problem on the Net of identity theft):

Click on image to enlarge.

Although the commemoration ‘act’ lasted only twenty minutes, I think it was intense and satisfying because it was so intimate and could not possibly have been held in a place more resonant with the events of 1914/15 for George and Kittie. The closing words of Nina’s letter to Kittie, four years after George’s death, were: ‘I clasp you close, Dina — Your T’Other’, which were almost unbearable. But the event had to be properly ‘closed’ and for that we turned traditional: we adapted the words of Laurence Binyon’s ‘For the Fallen’.

George, Kittie, Nina. We honour George’s sacrifice, and we cherish their memory. We will remember them.

We will remember them.

To be honest, it did occur to me that someone would say after this, ‘We can’t leave it there, can we? We must say something that rounds it off completely.’ If that happened, it seemed to me the swiftest way to ‘close’ would be to jump out of the secular and pronounce: ‘Rest eternal grant them, O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon them. May they rest in peace. Amen.’ For that purpose I had memorised the words in both English and Latin, but mercifully they weren’t needed, or I should have felt I had turned ‘parson’! Perhaps I should say that two Calderonians had made it clear some time before that they would attend a lunch but not a quasi-religious service; but a religious element is already present in Nina Corbet’s letter of consolation to Kittie in 1919.

The other, complementary and vital part of the day was the messages I received from people commemorating George even as we were. Mr Pym, at that time in the United States, emailed at 11.51 BST: ‘You will be in position as I write and I am with you in spirit’. It was 6.45 a.m. in Maine and he would be raising a glass to George’s memory over lobster that evening. From Croatia a follower who was much taken by George’s work with Rabindranath Tagore emailed to say she would be observing the day. Mr Derwent May of The Times, a keen appreciator of Calderon, emailed to say that he would be raising a glass over lunch where he was co-judging this year’s Hawthornden Prize. Harvey Pitcher, the Chekhov scholar and translator, did likewise with a friend in Cromer. Most arresting of all was to receive an email on 3 June from the military historian Peter Hart, whom I do not know personally but have frequently quoted on this blog, to say that he would be featuring George’s last letter in his tour next day ‘on the battlefield’, i.e. at Gallipoli itself.

In the evening, we were able to Tweet some photographs of the commemoration and thank everyone involved. I might add that it was also an occasion for me to thank the whole ‘Calderonia’ team, researchers, consultants, supporters and blogmaster, without whom it would have been impossible to write the biography in less than ten years, if ever!

By sheer stumbling, then, or serendipity, call it what you will, and thanks massively to modern computer technology, I think we arrived at a form of commemoration that was appropriate to these particular people, Kittie and George, and above all was twenty-first century. It made them seem modern, people of today like us, whereas in retrospect I can see that the church service would not have; it would have held them at a greater distance, a more solemn and unreal distance. I will admit to having woken up in a cold sweat a few nights before, wondering whether it would work, or someone might suddenly say ‘I can’t read this, it’s all over the top!’, but it seemed to work…

It was a huge relief when it was over and we could move to a more ‘Rabelaisian’ commemoration, but I think we will all remember it — and, of course, the subjects of it. I say ‘subjects’, because another thing that several of us felt strongly about was that the commemoration should be inclusive, i.e. not just celebrate George’s humbling act of sacrifice, but those others who were involved, entangled, engulfed by it.

Much discussion was had both before and afterwards about the issues of commemorating the fallen in this and the coming years of the centenary of the War. I hope to address some of these issues through two final posts on commemoration next week.

Next entry: ‘Tributes’

Related

Commemoration (to be continued 2)

Plan A for a commemoration of George’s death (see yesterday’s post) was really dictated by long accepted British forms of commemorative ritual. These have loosened up in recent years, of course, to a point where you have extended, all-singing-and-dancing customer-devised funerals and memorial services complete with video links to Australia, although an indulgent priest still presides. I actually think that the presence of a priest and a theological framework in which he/she sets death has a healthy restraining effect on the modern British tendency to secularised sentimentality — which is why I was pro plan A.

But we hadn’t asked ourselves what would have been most appropriate in the eyes of George and Kittie. As soon as I began to do this, I was struck by George’s words to Kittie in his letter of 10 May 1910: ‘Rejoice in the colour and vigour of the thing — and drink deep with jolly friends […] and other Rabelaisians. Your wishes for good, will work all the better when two or three of you are gathered together.’ Of course, the last nine words echo those of the Gospel, but it is characteristic that George is talking only of a secular, human impact of the ‘wishes for good’ shared between ‘two or three of you gathered together’.

The idea struck root, then, of a plan B that involved a very few people. After all, we could no longer accommodate scores because we no longer had the venue(s), so it had to be fewer rather than more. Then people started emailing from around Britain, from the EU, and from North America, to say they would ‘raise a glass’ to George on the day. The penny dropped that, in the 21st century, people could ‘commemorate’ anywhere on the globe, and at the same time, without being physically with you. And although we could no longer stage a ‘public’ commemoration, practically a memorial service, we could always stage one ‘in’ public: at Hampstead, near the very house that George and Kittie had lived in.

Reading the words ‘drink deep’ and ‘Rabelaisian’, I also suddenly remembered that George had referred in a letter to the ‘street café life’ of London that he liked so much. So a post-commemoration lunch in a restaurant that fitted that description seemed appropriate. Evidently he would have approved of it, Kittie probably too.

Mr John Pym, the grandson of the Calderons’ friends Violet and Evey Pym of Foxwold, and I, therefore went to Hampstead to reconnoitre and to sample a venue for the lunch. The space opposite the Calderons’ house was in fact ideal, and off the street, and Café Rouge on Hampstead High Street fitted George’s and our bill precisely. Where the invitees were concerned, at most a dozen could be accommodated on the verges of the public footpath, so the obvious candidates — the full available ‘Calderonia’ team plus spouses — were ideal, as they amounted to nine.

On 4 June, then, we nine assembled on the spot at 11.50, we read two pieces from Kittie’s memoirs and an officer’s diary relating to George’s departure for war and to the battle of 4 June 1915, we kept the two minutes’ silence at noon, then we read two verses from Laurence Binyon’s ode to George’s memory (see tomorrow’s post) and Nina Corbet’s letter of comfort to Kittie when George’s death was officially accepted in April 1919. Flowers were left, with a copy of the commemoration readings, for the owners of the former Calderon home, and we repaired to Café Rouge for a suitably Rabelaisian repast.

Over lunch the nine of us signed this commemorative programme (I can’t reproduce a signed copy, because of the problem on the Net of identity theft):

Click on image to enlarge.

Although the commemoration ‘act’ lasted only twenty minutes, I think it was intense and satisfying because it was so intimate and could not possibly have been held in a place more resonant with the events of 1914/15 for George and Kittie. The closing words of Nina’s letter to Kittie, four years after George’s death, were: ‘I clasp you close, Dina — Your T’Other’, which were almost unbearable. But the event had to be properly ‘closed’ and for that we turned traditional: we adapted the words of Laurence Binyon’s ‘For the Fallen’.

To be honest, it did occur to me that someone would say after this, ‘We can’t leave it there, can we? We must say something that rounds it off completely.’ If that happened, it seemed to me the swiftest way to ‘close’ would be to jump out of the secular and pronounce: ‘Rest eternal grant them, O Lord, and may light perpetual shine upon them. May they rest in peace. Amen.’ For that purpose I had memorised the words in both English and Latin, but mercifully they weren’t needed, or I should have felt I had turned ‘parson’! Perhaps I should say that two Calderonians had made it clear some time before that they would attend a lunch but not a quasi-religious service; but a religious element is already present in Nina Corbet’s letter of consolation to Kittie in 1919.

The other, complementary and vital part of the day was the messages I received from people commemorating George even as we were. Mr Pym, at that time in the United States, emailed at 11.51 BST: ‘You will be in position as I write and I am with you in spirit’. It was 6.45 a.m. in Maine and he would be raising a glass to George’s memory over lobster that evening. From Croatia a follower who was much taken by George’s work with Rabindranath Tagore emailed to say she would be observing the day. Mr Derwent May of The Times, a keen appreciator of Calderon, emailed to say that he would be raising a glass over lunch where he was co-judging this year’s Hawthornden Prize. Harvey Pitcher, the Chekhov scholar and translator, did likewise with a friend in Cromer. Most arresting of all was to receive an email on 3 June from the military historian Peter Hart, whom I do not know personally but have frequently quoted on this blog, to say that he would be featuring George’s last letter in his tour next day ‘on the battlefield’, i.e. at Gallipoli itself.

In the evening, we were able to Tweet some photographs of the commemoration and thank everyone involved. I might add that it was also an occasion for me to thank the whole ‘Calderonia’ team, researchers, consultants, supporters and blogmaster, without whom it would have been impossible to write the biography in less than ten years, if ever!

By sheer stumbling, then, or serendipity, call it what you will, and thanks massively to modern computer technology, I think we arrived at a form of commemoration that was appropriate to these particular people, Kittie and George, and above all was twenty-first century. It made them seem modern, people of today like us, whereas in retrospect I can see that the church service would not have; it would have held them at a greater distance, a more solemn and unreal distance. I will admit to having woken up in a cold sweat a few nights before, wondering whether it would work, or someone might suddenly say ‘I can’t read this, it’s all over the top!’, but it seemed to work…

It was a huge relief when it was over and we could move to a more ‘Rabelaisian’ commemoration, but I think we will all remember it — and, of course, the subjects of it. I say ‘subjects’, because another thing that several of us felt strongly about was that the commemoration should be inclusive, i.e. not just celebrate George’s humbling act of sacrifice, but those others who were involved, entangled, engulfed by it.

Much discussion was had both before and afterwards about the issues of commemorating the fallen in this and the coming years of the centenary of the War. I hope to address some of these issues through two final posts on commemoration next week.

Next entry: ‘Tributes’

Share this:

Related