Calderon arrived in London from Tahiti on 30 October 1906 and started writing his book about the island in November 1907. However, he soon gave it up to concentrate on his plays The Fountain and Cromwell: Mall o’Monks. Meanwhile, as Kittie put it in her Preface to the posthumously published book (Grant Richards, 1921), he carried out ‘laborious and exhaustive research into the history of the European influences to which the island had been exposed, for comparison with his own impressions’.

He finally settled down to write Tahiti in December 1913 and worked on it until, probably, the end of May 1914. It involved ‘returning’ to Tahiti in the spirit. He had to ‘recapture his old sense of the wonderful island’ and Kittie wrote that she remembered ‘the joy with which he told me that he was completely reliving those Tahitian days, that their atmosphere was all around him as he worked’. He had made dozens of pencil sketches on Tahiti, of which the overwhelming majority are of women.

‘Marae’ — pencil sketch by George Calderon, Tahiti 1906

Most of George’s sketches of people on the island were in fact made to illustrate the ethnic diversity of its inhabitants, as George was there in the first place as an ethnologist and anthropologist. Thus he writes that ‘Marae’ (above) illustrates ‘the Polynesian lips, protruding […] but finely and delicately formed’. He certainly studied her face closely:

It was no more than the daintiest pouting — the upper lip delicately retroussé in a very carefully modelled Cupid’s bow. She had the colour so often met in books, so seldom seen in real Polynesian life — a pale coffee no darker than a dark European’s. One could almost fancy a little ruddiness in her cheeks, her full, round cheeks; something European too in her eyes, royally full eyes à fleur de tête, like all the Polynesians, with the incredibly long curved eyelashes which all Polynesians have, and a sort of half-sleepy, half-timid veiledness in them.

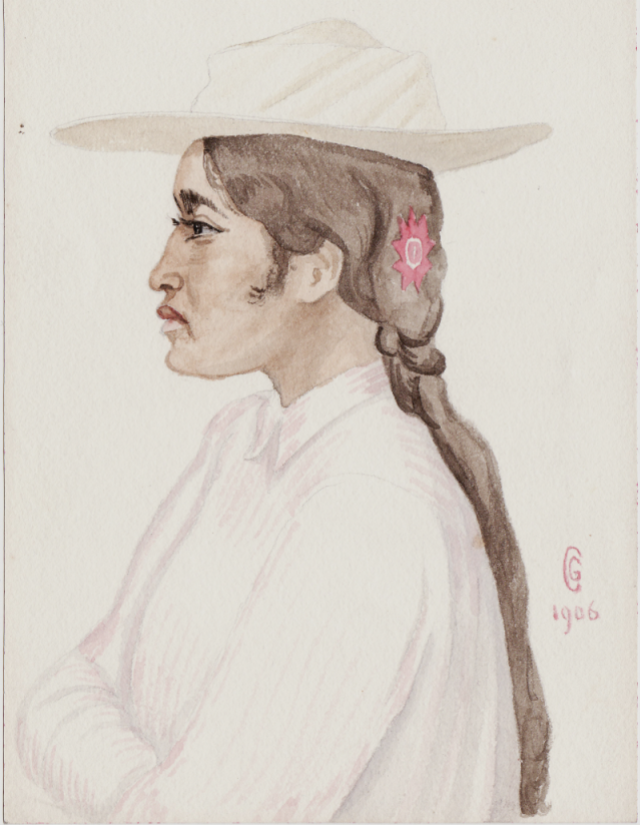

Some of George’s pencil portraits reproduced in Tahiti are very fine, and it is a tragedy that all the originals are lost. Some of the black and white illustrations, however, are actually of coloured watercolours, and a few of these have survived. The one I show below was not included in the book and is not captioned. Unusually, it is signed.

Unpublished watercolour by George Calderon, Tahiti 1906

I suspect that George put the book to one side when Ballets Russes arrived in London in the summer of 1914, as he would then be busy assisting Fokine. Obviously, he can have done very little on it between the outbreak of war and his return from Ypres in November. It was incomplete when he sailed for Gallipoli in May 1915, but he left what Kittie describes as ‘a synopsis which shows how he meant to construct it’. It’s my contention that he drafted this synopsis whilst he was convalescing at home in February 1915.

Next entry: ‘Le Bain de Loti’

Related

The return to Tahiti

Calderon arrived in London from Tahiti on 30 October 1906 and started writing his book about the island in November 1907. However, he soon gave it up to concentrate on his plays The Fountain and Cromwell: Mall o’Monks. Meanwhile, as Kittie put it in her Preface to the posthumously published book (Grant Richards, 1921), he carried out ‘laborious and exhaustive research into the history of the European influences to which the island had been exposed, for comparison with his own impressions’.

He finally settled down to write Tahiti in December 1913 and worked on it until, probably, the end of May 1914. It involved ‘returning’ to Tahiti in the spirit. He had to ‘recapture his old sense of the wonderful island’ and Kittie wrote that she remembered ‘the joy with which he told me that he was completely reliving those Tahitian days, that their atmosphere was all around him as he worked’. He had made dozens of pencil sketches on Tahiti, of which the overwhelming majority are of women.

‘Marae’ — pencil sketch by George Calderon, Tahiti 1906

Most of George’s sketches of people on the island were in fact made to illustrate the ethnic diversity of its inhabitants, as George was there in the first place as an ethnologist and anthropologist. Thus he writes that ‘Marae’ (above) illustrates ‘the Polynesian lips, protruding […] but finely and delicately formed’. He certainly studied her face closely:

Some of George’s pencil portraits reproduced in Tahiti are very fine, and it is a tragedy that all the originals are lost. Some of the black and white illustrations, however, are actually of coloured watercolours, and a few of these have survived. The one I show below was not included in the book and is not captioned. Unusually, it is signed.

Unpublished watercolour by George Calderon, Tahiti 1906

I suspect that George put the book to one side when Ballets Russes arrived in London in the summer of 1914, as he would then be busy assisting Fokine. Obviously, he can have done very little on it between the outbreak of war and his return from Ypres in November. It was incomplete when he sailed for Gallipoli in May 1915, but he left what Kittie describes as ‘a synopsis which shows how he meant to construct it’. It’s my contention that he drafted this synopsis whilst he was convalescing at home in February 1915.

Next entry: ‘Le Bain de Loti’

Share this:

Related