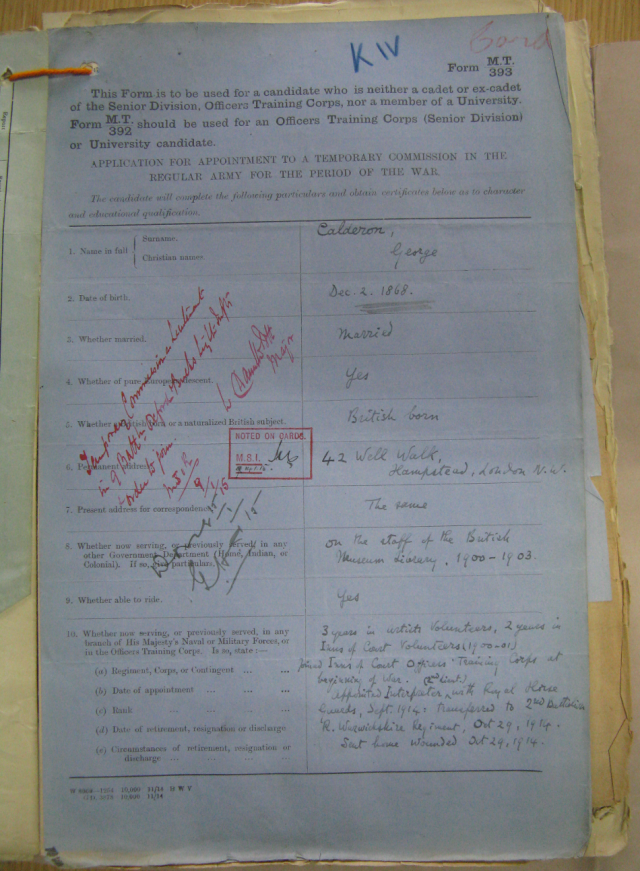

This is the final state of George Calderon’s application for a commission:

The writing in red ink across the left hand side of the form reads: ‘Temporary Commission as Lieutenant in 9 Battln Oxford & Bucks Light Inftr & order to join’, dated today 1915.

This was a coup. Although in December the War Office was claiming that George’s military status was that of Interpreter, not 2nd Lieutenant, now he was being given a commission as a full lieutenant and with a first-rate regiment. The Oxfordshire Light Infantry had been formed in 1881, renamed in 1908, and were commonly known as the ‘Ox and Bucks’. In 1914 their 2nd Battalion had fought from Mons to Ypres and covered itself with glory at Nonneboschen on 11 November.

The letters ‘KIV’ in blue at the top of the form refer to the fact that the 9th Battalion of the Ox and Bucks was part of ‘K4’, the 4th Group of ‘Kitchener’s Army’, i.e. the New Army raised initially from volunteers following the outbreak of war. K4 had been created in November 1914 with six divisions; the 9th Ox and Bucks was in the 32nd Division.

At the present moment, the 9th Battalion was a ‘Service Battalion’ under orders of 96th Brigade. This meant it could see action but had only a defensive role: its main object was to provide ‘combat service’ to the brigade, i.e. vital logistical support for operations. However, as we shall see, this could change.

Clearly George had passed his medical with flying colours, but how on earth had he then achieved this flip behind the scenes from the Corps of Interpreters to a highly respected combatant regiment?

The main mover, probably, was Sir Coote Hedley, who worked within the General Staff and (George’s file reveals) could communicate between War Office departments on other people’s behalf. ‘Much against my will’, Hedley wrote in 1920, ‘I did my best and he got his commission’. G.F. Bradby, a contemporary of George’s at Rugby, wrote later: ‘it was inevitable that […] he would somehow find his way into the firing line. The story of how he succeeded is a romance in itself — a romance of which only he could have been the hero.’

Service and Reserve battalions trained recruits, but they also trained men returning to duty after being in medical care — presumably including subalterns — so this too might be how Calderon slipped into the 9th Ox and Bucks. Equally, the Oxford connection may have helped. Francis Newbolt, Henry’s son, had been at Oxford like his father, and wrote to George praising his regiment on 6 December 1914. Possibly George knew other Oxfordians in the Ox and Bucks and they helped him? Perhaps there was a connection between the regiment and Trinity College, Oxford, where George had been an undergraduate?

The power of Oxford networks in Edwardian life can hardly be overstated (curiously, one hears less of the Cambridge ones!). As Brian Harrison has analysed in Separate Spheres: The Opposition to Women’s Suffrage in Britain (1978), and Julia Bush discussed in Women Against the Vote: Female Anti-Suffragism in Britain (2007), both male and female Oxford networks were prominent in the anti-suffrage movement with which George was associated. Oxford connections also played an important part in staging George’s translations of Chekhov’s plays in successful productions in 1909 and 1925.

Next entry: A review

Me again. Come on – all you other followers of Calderonia – I’d be very interested to read your comments too!

You ask if there was a connection between the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry and Calderon’s old College, Trinity. There was not, although five officers of that regiment are listed on the Board of Honour in the College’s War Memorial Library. One of these is Reginald Tiddy (1880-1916), the College’s first fellow and tutor in Oxford University’s new-fangled school of English Literature. Like Calderon, Tiddy appears in the Dictionary of National Biography. And like Calderon, he had considerable difficulty getting accepted for active service. My source for his life and military career is the biographical memoir that forms the preface of Tiddy’s only book, the posthumously published ‘The Mummer’s Play’ (1923). The author of the memoir was his close friend David Pye.

Reginald Tiddy was 34 at the outbreak of war and he had a muscular physique. He was a keen Morris dancer and enthusiastic member of the English Folk Dance Society. But he was also severely asthmatic and very short-sighted – ‘almost helpless without his glasses’.

He had no desire to fight. To Tiddy, Pye explained, War meant ‘the annihilation of all he valued’. But as early as September 1914 he wrote resolutely of his intention ‘to go to the army doctors and see if they will have me for a commission. I cannot honestly say I hope they will, as it seems to me that officers will stand a very poor chance of surviving this war, but I cannot really see how I can keep out of it, having had quite a fair amount of happy life, when these poor kids of twenty are being shot like this.’

Like Calderon, Tiddy went into training. In the autumn of 1914 he drilled with the Oxford University OTC, and while preparing for a series of lectures on Folk Literature at the British Museum, he joined with the Inns of Court OTC. Again, like Calderon. The two men had at least one mutual friend, Herbert Blakiston, President of Trinity College 1907–38. Did Calderon also know Tiddy’s fellow Morris enthusiast Cecil Sharp?

In December 1914 Reginald Tiddy was rejected for foreign service. He applied several times for a commission in a territorial battalion, but was rejected again. On December 12 he wrote to a friend, ‘Farquharson wants me to try for a Home Defence thing, so I’m going to, but unless one knows a Colonel there’s not much chance. I don’t!’ Tiddy was not entirely without influential friends however: Arthur Farquharson was a tutor at his undergraduate college, University, and a Lieutenant-Colonel in the OTC.

In January 1915 Tiddy travelled to Stockport where he was ‘once more ploughed for the Cheshires’. Still he did not give up. His next attempt was by means of ‘a deucedly strenuous time at Oxford in the “Special Course”, which starts at 7.40 a.m. every day. But I learn a great deal which might be useful some day… I was made to drill a squad and rather fetched the C.O. by the ferocity and swagger which I put on for his benefit, and by… my most brilliant smile.’ It worked. On 16 February 1915 Reginald Tiddy was gazetted as a second lieutenant and he joined the 2/4th battalion of the Oxford and Bucks at Northampton. Unlike Calderon, he was not a natural soldier. He found the training ‘devilish strenuous’ and had regular asthma attacks, and a long period of convalescence after flu. In November 1915 he was refused for overseas service by a medical board, and left the battalion. The published correspondence suggests that Farquharson tried hard to persuade his friend to transfer to the safer service of the Intelligence Corps – ‘where his faculties would be less wasted, and to leave the infantry work to others’ – but he was adamant. In January 1916 he wrote triumphantly, ‘I passed my medical board with great success, and my colonel tells me he will have me back if a vacancy occurs…’ He re-joined the battalion in March, and sailed for France in the middle of May.

Reginald John Elliot Tiddy was killed by a shell falling in the trenches near Laventie in Northern France on the night of 10 August 1916.