As I have written before, the question everyone asks me is: ‘Who is George Calderon?’ Perhaps unconsciously, some people seem to intonate this as a rhetorical question implying: ‘Why are you spending years of your life writing about a person nobody has ever heard of?’ No-one has ever asked me why I think he should be remembered, in other words why I believe he deserves a full-length biography. Perhaps, then, this limbo between his death and the blog returning to ‘real’ 1915 time is an appropriate moment to address those unasked questions — in effect, to pay him my own tribute.

In my opinion George Calderon was the best-informed and most critically-thinking Slavist that Britain produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The other big names were grammarians (Morfill, Goudy), ‘old Russia hands’ (Wallace Mackenzie, Baring), historians (Pares, Seton-Watson), or hopelessly acculturated literati (Maude, Graham). Where Russia was concerned, George did not specialise like these figures, he engaged with it as a complete cultural presence in real and historical time. He experienced it, he ‘entered into’ it, he ’empathised’ with it, he deeply researched aspects of it, but he did not ‘catch the Russian virus’, he ‘came out of’ Russia again and turned his own critical but sympathetic mind on it. His approach was holistic, yet at times almost semiotic in its rigour. As a Russianist and Slav folklorist/anthropologist he was far ahead of his time.

The fact that George, at the age of 27, witnessed the Khodynka tragedy during the 1896 celebrations of Nicholas II’s coronation, when 1300 people were trampled to death in Moscow, meant that he had no illusions about Russia; the experience undoubtedly marked him for life. Yet his sense of the comic and the absurd (one of his favourite authors was Lewis Carroll) not only equipped him to survive three years in Russia, it enabled him to apprehend Russia at a deeper level. Chekhov too called Russia ‘absurd’, ‘disjunctive’, and had a love of verbal nonsense. At the same time, George’s driving sense of beauty enabled him to appreciate the best in Russian art from icons and the Old Russian byliny (lays) to Fokine, with whom he worked, and Rakhmaninov, whose music he played.

The articles, reviews and essays on Russian literature, folklore and drama that George produced between 1900 and 1913 can claim to be the most interesting, original and critical corpus of English writing about Russian culture published in the first third of the twentieth century. His literary judgements of Korolenko, say, Gorky, or Leonid Andreyev’s plays, are difficult to fault today. His 1901 analysis of the pernicious cognitive dissonance of Tolstoy’s ‘philosophy’ was not equalled until George Orwell’s 1947 essay ‘Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool’. As I discussed in my post on 13 February, I believe that Calderon’s introduction to his 1912 volume Two Plays by Tchekhof is still the most outstanding piece of writing in English about Chekhov’s plays and their significance for the British stage.

If we look at George’s translations of Chekhov, and his own 1909 production of The Seagull, in the longue durée of British theatrical history, we can see that they had a more telling impact on the early process of acceptance of Chekhov’s plays in English than anyone else’s. Oxford networks played a crucial role in the successful productions of their alumnus’s versions of The Seagull (1909) and The Cherry Orchard (1925). It is quite conceivable that but for George’s efforts Chekhov would not be the most popular classical playwright after Shakespeare that he is in Britain today, or have had the penetrating influence on British theatre, film and television that he has. As I discussed in my posts of 11-12 February, Constance Garnett’s translations of Chekhov’s plays may have had a longer life than George’s as ‘literals’, but his are the only ones crafted in a contemporary, avantgarde English theatre-language by a Russianist who was also a playwright. In this respect, the only person who can compare with him is Michael Frayn.

As a creative writer himself, the most admirable thing about George Calderon is that he never stood still. Having mastered what one might call the ‘Late Victorian comic short story’, he produced a best-selling Early Edwardian burlesque, The Adventures of Downy V. Green, Rhodes Scholar at Oxford — which seems to have had an afterlife stretching from the 1938 film A Yank at Oxford down to its 1984 remake Oxford Blues. In his political satire Dwala, the very ‘anarchy’ and cinematic jerkiness that reviewers held against it show that George Calderon was moving towards modernism. Dwala almost certainly influenced Aldous Huxley’s novels.

In his plays, George was constantly experimenting. The Fountain was certainly his take on the new Theatre of Ideas, but audiences vastly enjoyed its conservative displacement of Shaw. George’s Cromwell is different again: a verse morality play in the early Tudor style about (heretical) ambition. His last full-length play, Revolt, displays the influence of Chekhov’s ensemble writing, but also of Expressionist film techniques. I think all of these plays are capable of a stage life today in the hands of a good dramaturg. Meanwhile, George’s unpublished libretti for Fokine and his published one-act plays show him working with Islamic subjects, French farce, theatre of mood, ‘mimo-drama’, Symbolist drama… There is no doubt that these works were at the cutting edge of Edwardian modernism. When Harold Hannyngton Child wrote in The Times of 27 July 1922 that ‘one is inclined to say that Calderon’s loss was the heaviest blow which struck the English drama during the war’, he was echoing the view of many.

Ever since Virginia Woolf suggested that ‘on or about December 1910 human character changed’, a touchstone of contemporaries’ attitudes to modernism has been their response to the first exhibition of Post-Impressionist paintings that opened at the Grafton Gallery, Mayfair, on 8 November 1910. George Calderon defended most of these paintings vigorously in an article in the New Age. He concentrated on Gauguin, comparing the ‘great patch of red hair’ of his Christ in the Garden to Sharlotta Ivanovna producing a cucumber and eating it in Act 2 of The Cherry Orchard; for ‘the reality of their inconsequences raises the value of their adjacent pathos’.

During successive periods of liberal and socialist consensus in Britain, it was possible to dismiss George Calderon as a ‘reactionary’ opposed to women’s rights and the unions. Closer acquaintance with what he actually said about suffragism and unionism shows his beliefs to have been far more complex. Like the overwhelming majority of women in Britain during his lifetime, George believed that women were best at philanthropic activity in the local community, where they already had the franchise; the State might have been created by males, but without the dedicated work of hundreds of thousands of real women in the real Community the State in the wider sense would have collapsed long ago. As George moved further and further from the Men’s League for Opposing Woman Suffrage (which women could not join) and worked with the far larger Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (which men could join), he came to appreciate more and more women’s ‘sphere of activity’ in Edwardian society, which they believed precluded a need for the parliamentary vote. ‘Antis’ like Mary Ward, Lady Jersey, Violet Markham, or Gertrude Bell, were feminists in their own right. As Julia Bush has written in Women against the Vote: Female Anti-Suffragism in Britain, ‘from a longer-term perspective these women’s sturdy defence of gender difference was also far from irrelevant to later generations’. In any ‘broader project to restore neglected conservative dimensions to women’s history’, as Bush puts it, George’s stance and activism deserve to be considered.

On the question of the power of the unions, Calderon’s loyalty was to the community and one nation. He made it quite clear in print that he supported miners’ and dockers’ demands for living wages and good working conditions. He supported the right of workers to strike against employers. But in 1912 he was profoundly disturbed by the spectacle of miners coercing the whole nation and ‘enjoying this wild dream of limitless power’. He foresaw the unions sidelining the legitimacy of elected government and their leaders becoming powerful shoguns. In the longue durée of twentieth century British politics George was prescient. He believed that the answer was for the ‘Community’ to defend itself — which happened in the 1919 Railway Strike and the General Strike of 1926. George’s political philosophy, therefore, was holistic, communitarian, inclusive, individualistic, centrist. Possibly, even, it was influenced by his contact with the women’s movement. Again one can see resemblances to the philosophy of modern conservatism; again one can see that as a conservative thinker he was ‘far from irrelevant to later generations’.

Both George and Kittie gave huge amounts of their personal time and energy to the causes of conservative women and the community in the first decade of the twentieth century, not to mention sums of money from their personal funds. They both believed that the individual had a responsibility to get involved in politics and that personal activism could make a difference. It was this that led Martin Shaw to call George ‘the honestest man I have ever met’: ‘Once he felt a thing to be right, he pursued his path — alone if need be, but disregarding entirely the world’s valuation.’ Many of George’s friends, unfortunately, had no political beliefs of their own, only the reflexes of contemporary political correctness.

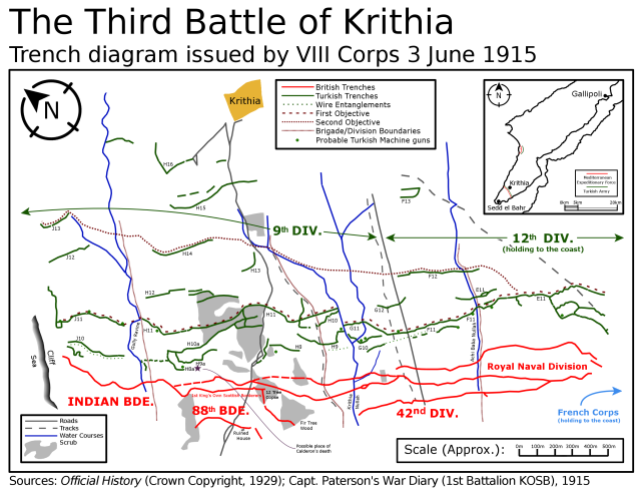

George’s resourceful determination to become a combatant in World War I at the age of forty-five can be seen as a natural extension of this ‘propensity to act’; although there was undoubtedly an element of adventurism to it as well. He had long believed that if war with Germany came he must join up and fight, and as Laurence Binyon expressed it, ‘what he believed, he did’. At Gallipoli on 4 June he made the supreme sacrifice. Being supreme, it was neither more nor less than that of millions of other men who were not professional soldiers and were not conscripted. Yet as his biographer I am particularly aware of the richness, talent and achievement of his pre-1914 life that he ‘threw away’, and aware of whom he sacrificed in his wife. In its completeness and absurdity, there is something ‘yearningly tender’, to use Kittie’s phrase, about George’s ‘Greater Love’.

Finally, I feel a boundless admiration for his posthumous masterpiece, Tahiti. Unlike Gauguin, Brooke and others, George did not go to the island for sex. What he brings breathtakingly alive about the many women he met on Tahiti is their beauty, yes, but also their aesthetic sophistication, their taste, their true gentility and caring for other people. It may not even have been wholly true, but it is inspiring. The book itself seems to me the most complete embodiment of George’s personality: ‘a perfectly delightful one’, as the educationist and social reformer Isabel Fry put it in a letter of 1932 to Kittie, ‘delicate and stalwart, sympathetic but no sentimentalist’. No facet of life on the island is overlooked, from its people to its plants, its folklore to its food, its nutters to its bureaucrats, its music to its barbed wire. All are looked at steadily by an eye inclined now to humour, now to wonder, now to acerbity. If Chekhov’s Sakhalin is the complete study of an island that was ‘hell’, George’s is quite comparable as a study of an island that was ‘paradise’. It has remained in print all over the world.

But, it may reasonably be objected, don’t all these areas of interest and activity simply prove that Calderon was the epitome of Edwardian dilettantism?

Thirty years ago, when I first made his acquaintance through Russian Studies, I believed that myself. It seemed self-evident. What other explanation, or view, could there be of so many ‘disparate’ pursuits, of a man so ‘various’? Furthermore, he seemed to pick one interest up, become possessed by it for a while, then throw it away and move on — the hallmark, surely, of the dilettante? Thus, one might claim, he never achieved a stable identity, has never been taken very seriously, nobody knows who he is…

It is understandable that with our 2015 views on ‘professionalism’ and ‘specialisation’ we should jump to these conclusions about George Calderon, but the years of researching his biography convince me that they would be wrong. First, as I have tried to show above, George did not ‘dabble’ in things, he achieved real distinction in whatever he touched. As a Russianist he was first-rate, as modernist satire Dwala is first-rate, as a dramatist he was genuinely innovative, as a political thinker he was ahead of his time, as an anthropologist he was brilliantly holistic and speculative, as a man with the propensity to act he was consistent. Although Percy Lubbock, ten years younger and of an utterly different cast of mind, presented George in his Sketch from Memory as someone who ‘knew precisely the moment he had made his peculiar contribution to a cause’ and would then ‘be gone, like the Red Queen at the end of her marked course’, a more interior knowledge of him through his archives shows that this was not generally true. For instance, he may seem to have dropped the anti-suffrage movement in 1910, but it was merely the Men’s League for Opposing Woman Suffrage that he dropped. In 1914 he was still working on Slavonic folklore and paganism, he was pushing Tahiti forward, completing ballet libretti, creating a one-act play to equal The Little Stone House, and writing a modern pantomime with William Caine and the composer Martin Shaw. He did not ‘drop’ these pursuits for the War; he would have returned to them and taken them to their conclusion.

I believe, then, that in George Calderon we are not dealing with an Edwardian dilettante, but with a ‘quantum’ personality — a phenomenon of multi-giftedness and multi-tasking that I call ‘Edwardian genius’. His was a superbly fulfilled life in all its facets, despite so many artistic projects remaining unfinished. The nature and energy of his achievement, the integrity of his life in every sense, are, I am convinced, worth trying to understand in a biography and drawing to a modern readership’s attention. He was an admirable, self-fulfilled individualist, from whose ‘portfolio life’ we might learn much.

As a man, he was sociable, sportive, very funny, theatrical, uxorious, flirtatious, a chain-smoker, desperately hard-working, stalwart, staunch, and…did not suffer fools gladly. I fear he would have instantly classified me as a bull-shitter. But perhaps, just as I was at first repelled by his ‘Edwardianness’ — his slightly menacing look of clean-shaven stiff-upper-lippedness à la Henry Newbolt — so too, perhaps, he might eventually have come round to liking me a twentieth as much as I have come to like him. That makes me smile.

PATRICK MILES

Next entry: Kittie

Action

Both Constance Sutton (Astley) and Nina Corbet (Astley) knew only too well the nervous and physical effects that anxiety tended to have on Kittie.

But Kittie had her own well-developed pattern of techniques for coping with it. She clung to her faith in benign outcomes (was ‘stalwart’ and ‘stout’), believed in taking positive action, and sought the company of friends for comfort.

Today, Sunday 13 June 1915, she went to church and prayed for George’s safety. Telegrams were delivered on a Sunday, but none came. She decided she must do something, but what? The War Office was basically saying ‘wait for our next telegram’, so on what pretext could she get back to them and try to hurry them up?

She noticed that in the telegram George had been described as ‘2nd Lieutenant Calderon’, when he was certainly Lieutenant. Although Calderon was hardly a common English name, the error could be made out to be significant in tracing him through the military hospital system. She therefore probably went this evening to see the ‘Godfather in War’, Coote Hedley (q.v.), not far away in Belsize Avenue, and persuaded him to write an internal note at the War Office to the Casualties section pointing out George’s true rank. This he did next day.

She also wrote to Gertrude Bell, who was running the ‘Enquiry Department for Wounded and Missing’ at the British Red Cross and Order of St John in Arlington Street. Bell was a brilliant administrator, linguist and archaeologist, who had been George’s counterpart in the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League when he was Honorary Secretary of the Men’s League for Opposing Woman Suffrage. They got on well and she thought highly of him. But for him, she wrote to George on 18 July 1910, the anti-suffrage demonstration in Trafalgar Square on 16 July, which was meant to be a joint WNASL and MLOWS event, would have been a ‘disaster’ scuppered by MLOWS misogynists.

It is possible that Kittie had not known of Bell’s war work until told by Percy Lubbock, Violet’s brother. He was working for the British Red Cross at Arlington Street himself, as his extremely poor eyesight meant he could not sign up. Percy (1879-1965) was gay, had greatly admired his uncle Archie Ripley, Kittie’s first husband and George’s Oxford friend, and he became very supportive of Kittie from now on.

Whether Kittie had yet told George’s mother Clara that he was ‘wounded’, we can only speculate. Perhaps she was waiting first for confirmation.

Next entry: 14 June 1915