Since this blog started in July last year, I have taken part in many conversations, both viva voce and online, about followers’ responses to George Calderon’s war experience, to the War as it has been unfolding, and to what I can only call the process of commemoration of World War I as we are experiencing it in Britain. With less than a month to the closing of the blog, it is perhaps appropriate to present some of those responses (without attributing them), and some of my thoughts about them. The subject is, of course, complex, perhaps unsurveyable in depth and breadth. I would like to be able to give a reasoned, joined up argument about it, but I have attempted to do this over several hours and failed, so I must ask you to be indulgent to these fragments.

* * *

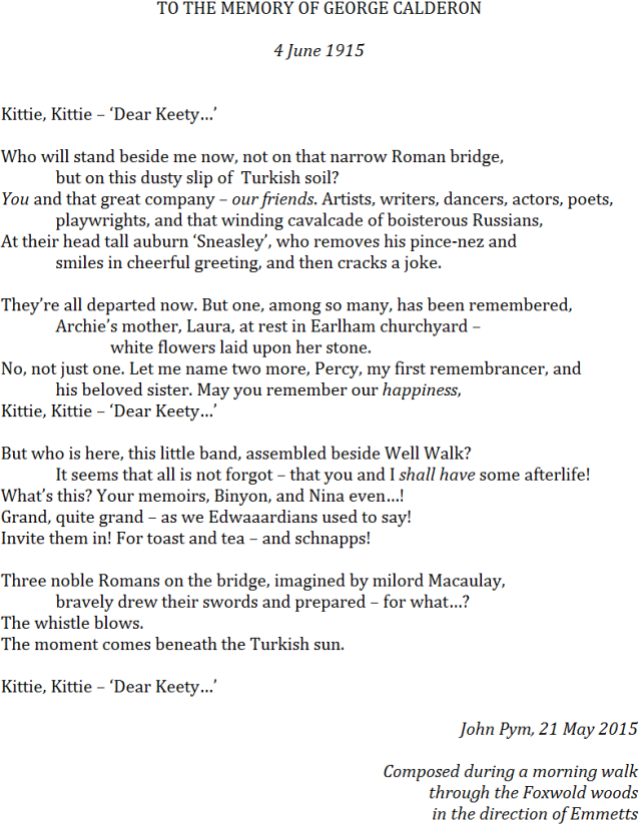

I was moved by John Pym’s poem ‘To the Memory of George Calderon’, which I posted yesterday, and I imagine followers were too. In a sense, Mr Pym has known George Calderon longer than I have. He heard about him and Kittie from his own grandfather, Evey Pym, who features from day one of this blog, and the Calderons’ spirits, so to speak, still hung in the air when Mr Pym’s father Jack, his uncle Roly, and aunt Elizabeth (George’s god-daughter), lived at or visited Foxwold as adults. Mr Pym is also, of course, familiar with the literature about George, starting with his great-uncle Percy Lubbock’s 1921 Sketch from Memory. Thus, although John Hussey (Finding Margaret: The Elusive Margaret Bernardine Hall, 2011) can speak of George’s ‘legendary sangfroid’, I know that George’s emotional openness in Mr Pym’s poem is based on both knowledge and understanding of the man, and personally I find it convincing.

John Pym’s poem is a marvellous example of empathy; an empathetic act doubtless facilitated by the spirit of the place in which it was composed.

But it is not all empathy. The quotes around ‘Dear Keety’ indicate that although these two words are George’s in origin, they are being uttered by the author; the author, Mr Pym, is (barely perceptibly) intruding himself here. The refrain is in a double voice. George’s words ‘Kittie, Kittie’ have George’s sangfroid, Mr Pym’s ‘Dear Keety’ have a catch in them. And I venture to suggest that they produce that catch of emotion in the reader too.

It’s this ‘catch of emotion’ that all of us, surely, have experienced again and again since the commemoration of World War I began last year. The ‘re-lived’ emotion of the Declaration of War on 4 August gripped the nation. Millions felt the desire to put burning candles on their windowsills and snuff them out at midnight in commemoration of Sir Edward Grey’s famous words. Thousands upon thousands visited the sea of poppies at the Tower, and as far as I know every single flower was bought afterwards. A large photograph of the installation, with a sober caption, appeared in the German newspaper Die Zeit.

Above all, though, the commemoration of World War I, and this blog, produce catches of emotion that we cannot hold. We know too well those moments of shading the eyes, turning away, spluttering, weeping, sobbing. On 4 August I was overwhelmed by the tragic solemnity of the moment and, frankly, by the challenges of the journey ahead on the blog. In October, when Calderon was at Ypres, I was walking through Cambridge when I just thought of George and Kittie’s situation, penetrated it more empathetically I suppose, and burst into tears muttering their names. Followers have told me of similar moments, for instance 10 November 1914 when George was in hospital, learned of the death of his commanding officer, and himself ‘downright cried’, which Kittie said was ‘so unlike him’; and especially up to, on, and immediately after 4 June 1915. At our own commemoration in Hampstead on 4 June there were moments of ‘catch’ in all the readings, even though by then we had read the texts to ourselves several times.

* * *

I think it will be quickest to present the conversation we have had about these issues by resolving it into the key questions it has raised:

What triggers such intense emotions in us about the War or George and Kittie’s story? What are these actually emotions of? Is it a form of grief or bereavement? Have we as a nation suddenly become emotionally more ‘vulnerable’, indeed tearful, indeed maudlin? How often can one experience these emotions about the war dead before our feeling loses authenticity? Have we come to enjoy being moved in this way? Have we become addicted to it? Is there anything wrong about that? Is there any harm or danger in it? Can we sustain this emotional response to the War another four years? Will we expect ‘closure’ on our re-living and commemoration of this war? Do the British as a nation need ‘closure’ now on World War I?

I cannot answer all these questions, but I shall attempt to allude to them all.

* * *

As Santanu Das’s book Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature (2005) examines so admirably, the terrible, Apocalyptic worlds of the Western Front and Gallipoli were themselves almost unbearably ‘touchy and feely’. I suggest that we all ‘know’ this, by which I mean we have already ingested deep into our psyches not only the images of mud, corpses and no man’s land, but this context of human intimacy in extremis.

Perhaps this is why it is so often small, even trivial, personal details that can trigger in us such unwithstandable emotion. Archivists work in archives with papers covered in words, but as Das himself says, the stains of trench mud on a letter and ‘a bunch of blue and white flowers, the dried stalks still green pressed onto the letter’ — the ‘material tokens of memory’ — are almost too ‘intimate and unsettling’. The fact that ten-year-old Lesbia Corbet had already tried on her bridesmaid’s dress for her brother Jim’s wedding when he was killed at Givenchy (see my posts of 15 and 17 April) is of a similar order; or George’s arachnophobia as shells are flying overhead at Gallipoli. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission is currently tweeting inscriptions on gravestones: ‘I’m all right mother cheerio’ is a fair example of how overwhelming their brevity and authenticity can be.

These small things instantly transport us to the reality of the person and his/her predicament linked to the War; simultaneously they access all we know and feel about the tragedy of World War I; and it is often far too much to bear. I think initially, as one holds the letter with the pressed flowers, say, or reads the living inscription, one’s feelings are akin to grief and bereavement, because one momentarily feels one knows that person. But one also knows they were killed next day, or their women’s and families’ lives destroyed, and those are the ‘impossible’ facts that can engulf one. In a word, I think that what commemoration in 2015 does, whether in the form of a service, or heart-rending biographies of the fallen, or the reading of war poetry, or the viewing of personal items in glass cases at an exhibition, is make us re-experience to the full the pity of war.

Where the blog is concerned, I think it is also the pity of George and Kittie’s lives that followers, and I, sometimes find too much. There is no space here to define or analyse this ‘pity’, or what Wilfred Owen meant by ‘the pity of war’, but I do not think that is necessary.

* * *

I happen to believe it is our own empathy that enables us to be so moved by these small items or details, or aspects of commemoration, and I believe that there has been an enormous increase in the recognition, understanding and cultivation of empathy in Britain in the last thirty years or so. Europeans and North Americans remark on it. We increasingly believe that ‘feeling into’ a person’s situation is vital to our emotional understanding of them and to our own ’emotional intelligence’ (a phrase, incidentally, that George was one of the first to use in print, in 1911). Surely this is a good thing?

Kierkegaard wrote: ‘The majority of men are subjective towards themselves and objective towards all others, terribly objective at times — but the real task is in fact to be objective towards oneself and subjective towards all others.’ That is true empathy. But obviously, if our empathy is restricted to ‘putting ourselves in other people’s shoes’ and feeling and thinking what we would experience in those shoes, it risks being about ourselves rather than others. The possibility is always there that our pity is merely a rush of self-pity.

* * *

We certainly have become more ‘tearful’ as a nation, but I think one reason is that society has become theatricalised almost to saturation. Crimes, disasters, public inquiries, very recent political history, are instantly translated to the television screen, the computer screen, film or the stage. Bizarrely — to older generations — an historical event like Waterloo is no longer just commemorated, it has to be ‘enacted’ (not ‘re-enacted’), and the media even talk of ‘Napoleon’ or ‘Wellington’ when they mean the actors impersonating them. We are invited by the media to respond to real events as theatrical performances. Above all, we are an instantly self-imaging society. We are therefore more used than ever to responding to a third term: the imaged, quasi-dramatic representation of people and events, rather than the individuals and the events themselves. Within hours of a disaster anywhere in the world, we can watch ‘footage’ of it and emote about it. In May 1915 Britons had a newspaper with one archive photograph of the Lusitania on its front page.

If the paradigm of our twenty-first-century empathy is theatre, can we learn anything from the experience and tradition of audience empathy in the real theatre?

Possibly. I have said already that I think our powers of genuine empathy access the ‘tragedy’ of the War, and if by that we mean something complexly, unbearably ineluctable, then those feelings are akin to the fear and pity of the greatest tragic plays.

In that context, Aristotle’s concept of ‘catharsis’ might look applicable. Unfortunately, theatrical catharsis is most commonly thought of as ‘purifying’, ‘purging’, getting rid of the strongest emotions we are capable of through empathy in the theatre. It is true, I believe, that the notion of bowel evacuation or surgical bleeding is present in Aristotle’s original concept. But how can this help us in coming to terms with the tragedy of the fallen in World War I? It seems too much as though it is designed to produce anaesthesia; a ‘closure’ and ‘return to equanimity’ indistinguishable, perhaps, from indifference.

In truth I don’t believe theatrical catharsis is about an audience getting rid of visceral emotions, it is about these emotions enabling us to face what we are seeing on the stage and know exists in real life. In this sense, there can be comic as well as tragic catharsis. I believe a fragment of Mikhail Bakhtin’s expresses theatrical catharsis more accurately: ‘Tragedy and laughter look being in the eyes equally fearlessly, they do not construct any illusions, they are sober and exacting.’ Nadezhda Mandel’shtam also made a vital distinction, when she said that ‘genuine tragedy is rooted in an understanding of the nature of evil, and only that tragedy can bring us catharsis’. If our empathetic response to the commemoration and ‘material tokens of memory’ of World War I helps us to look being and evil in the eyes fearlessly, to dispense with all illusion about this human tragedy, then perhaps catharsis is the right word for what we are going through in these four years.

* * *

It is interesting that psychologists use the word ‘catharsis’ in the sense of ‘the purging of the effects [my italics] of pent-up emotion and repressed thoughts, by bringing them to the surface of consciousness’ (Chambers). On ‘the surface of consciousness’, presumably, they are more likely to be cognitively, intellectually, rationally understood — and their sources faced. I therefore think that the identity with theatrical catharsis, if we accept Bakhtin’s and Nadezhda Mandel’shtam’s descriptions of it, may hold.

The point is, empathy is not an end in itself. I have always felt that the limits of empathy must be understanding. You ‘feel in’, you must attempt to be fully ‘subjective’ to others, but this is the beginning of a process. The process should be towards understanding, indeed ‘knowing’ — not knowing in a closed-off sense, but a rational knowing that is momentarily at rest and secure, that ‘looks being in the eyes fearlessly’, perhaps. It is a process that should lead to knowledge and intelligent action.

Are there people who are capable of great empathy but refuse to reach beyond it? I would say that the personal life of the late Princess of Wales, who is often credited with our ‘discovery’ of empathy as a nation, suggests there are. I have also had colleagues with superb powers of emotional understanding, but who felt no need to use them to help students actually solve their problems.

* * *

If the effect of an empathetic response is true cathartic understanding, I see no reason why there is anything wrong, harmful or dangerous about repeating the experience. We do not suggest that seeing one Agamemnon or King Lear is enough. All the time we have an authentic empathetic response to the ‘tokens of memory’ of the War, we are learning. I see no reason why we cannot sustain our emotional response to it for four years if that emotional response is always pure, ‘exacting’, committed to cathartic understanding, and does not degenerate into self-indulgence. I admit that empathy can be exhausting, but our gains in understanding of the tragedy that was the War can be immense.

The Sirens of sentiment, though, lie always in wait. The concept of ‘tragic pleasure’ has always been a dubious one, and we all know how easy it is to fall into enjoying strong feelings. The more they are repeated, the greater the temptation to become addicted to them. Again, I think the blanket theatricalisation of our lives encourages that: we are asked to respond physically to all the media spectacles around us and we end up always crying, or always demonstratively sweeping the (sometimes non-existent) tears from the corners of our eyes like, well, bad tragedians.

* * *

In fine, the conversation is about authentic empathy and its surrogate, sentiment. We associate sentimentality more with the Victorians than the Edwardians, so Laurence Binyon’s words to Kittie about his memorial ode to George (see my post of 25 June) are all the more interesting. Here is the author of the most quoted and, many would say, most emotionally churning poem to come out of the First World War, drawing back from emotionality because of what George was: ‘I wanted to be as exact as I could, and the thought of him cannot be anything but tonic, an astringent to sentiment.’ It is a salutary reminder, a warning against the pleasurable emotional response to the Last Post or ‘For the Fallen’; an astringent from George Calderon himself.

* * *

‘Closure’ has been defined as ‘the evolution of emotions to make them more stable and bearable’ and, less positively, as ‘a feeling of satisfaction or resignation when a particular episode has come to an end’ (Chambers).

It would be interesting indeed to hear the response of ‘professional’ psychologists, psychotherapists and bereavement counsellors to the conversation about this subject that we Calderonians and blog followers have had over the last year and which I have endeavoured to display above. However, I believe that we all have a right as ‘amateur’ psychologists yet full-time human beings, to present our take on it.

I have to say that I meet very few people in the theatre who believe in ‘closure’. This is probably because their life’s work is with empathy, emotions, and the expression of them. They rely on their emotional memory being open and accessible. They cannot just ‘close off’ those sources of their lives as actors or directors. It would be self-destructive. It would be to deny the existence, the goodness, of those sources.

Similarly, I feel that the tragedy of the First World War, for nations and for individuals, is so immense and so important to us that we should never seek ’emotional closure’ on it, just as a German president has said that for his nation there can never be ‘moral closure’. We always need our empathetic response to the fallen, and to the survivors, in order to relate to them fully as human beings. To remember them emotionally is the most human form of memory. We need to do this forever, in order to understand the lessons of this War and, I believe, to keep renewing ourselves as a nation.

I am especially grateful to Clare Hopkins, Archivist of Trinity College, Oxford, for her extended contributions over the past year to the conversation about Commemoration. (Click here for a comment by Clare with her thoughts on the subject.)

Next entry: Letter from Alexandria

Commemoration (concluded)

Since this blog started in July last year, I have taken part in many conversations, both viva voce and online, about followers’ responses to George Calderon’s war experience, to the War as it has been unfolding, and to what I can only call the process of commemoration of World War I as we are experiencing it in Britain. With less than a month to the closing of the blog, it is perhaps appropriate to present some of those responses (without attributing them), and some of my thoughts about them. The subject is, of course, complex, perhaps unsurveyable in depth and breadth. I would like to be able to give a reasoned, joined up argument about it, but I have attempted to do this over several hours and failed, so I must ask you to be indulgent to these fragments.

* * *

I was moved by John Pym’s poem ‘To the Memory of George Calderon’, which I posted yesterday, and I imagine followers were too. In a sense, Mr Pym has known George Calderon longer than I have. He heard about him and Kittie from his own grandfather, Evey Pym, who features from day one of this blog, and the Calderons’ spirits, so to speak, still hung in the air when Mr Pym’s father Jack, his uncle Roly, and aunt Elizabeth (George’s god-daughter), lived at or visited Foxwold as adults. Mr Pym is also, of course, familiar with the literature about George, starting with his great-uncle Percy Lubbock’s 1921 Sketch from Memory. Thus, although John Hussey (Finding Margaret: The Elusive Margaret Bernardine Hall, 2011) can speak of George’s ‘legendary sangfroid’, I know that George’s emotional openness in Mr Pym’s poem is based on both knowledge and understanding of the man, and personally I find it convincing.

John Pym’s poem is a marvellous example of empathy; an empathetic act doubtless facilitated by the spirit of the place in which it was composed.

But it is not all empathy. The quotes around ‘Dear Keety’ indicate that although these two words are George’s in origin, they are being uttered by the author; the author, Mr Pym, is (barely perceptibly) intruding himself here. The refrain is in a double voice. George’s words ‘Kittie, Kittie’ have George’s sangfroid, Mr Pym’s ‘Dear Keety’ have a catch in them. And I venture to suggest that they produce that catch of emotion in the reader too.

It’s this ‘catch of emotion’ that all of us, surely, have experienced again and again since the commemoration of World War I began last year. The ‘re-lived’ emotion of the Declaration of War on 4 August gripped the nation. Millions felt the desire to put burning candles on their windowsills and snuff them out at midnight in commemoration of Sir Edward Grey’s famous words. Thousands upon thousands visited the sea of poppies at the Tower, and as far as I know every single flower was bought afterwards. A large photograph of the installation, with a sober caption, appeared in the German newspaper Die Zeit.

Above all, though, the commemoration of World War I, and this blog, produce catches of emotion that we cannot hold. We know too well those moments of shading the eyes, turning away, spluttering, weeping, sobbing. On 4 August I was overwhelmed by the tragic solemnity of the moment and, frankly, by the challenges of the journey ahead on the blog. In October, when Calderon was at Ypres, I was walking through Cambridge when I just thought of George and Kittie’s situation, penetrated it more empathetically I suppose, and burst into tears muttering their names. Followers have told me of similar moments, for instance 10 November 1914 when George was in hospital, learned of the death of his commanding officer, and himself ‘downright cried’, which Kittie said was ‘so unlike him’; and especially up to, on, and immediately after 4 June 1915. At our own commemoration in Hampstead on 4 June there were moments of ‘catch’ in all the readings, even though by then we had read the texts to ourselves several times.

* * *

I think it will be quickest to present the conversation we have had about these issues by resolving it into the key questions it has raised:

What triggers such intense emotions in us about the War or George and Kittie’s story? What are these actually emotions of? Is it a form of grief or bereavement? Have we as a nation suddenly become emotionally more ‘vulnerable’, indeed tearful, indeed maudlin? How often can one experience these emotions about the war dead before our feeling loses authenticity? Have we come to enjoy being moved in this way? Have we become addicted to it? Is there anything wrong about that? Is there any harm or danger in it? Can we sustain this emotional response to the War another four years? Will we expect ‘closure’ on our re-living and commemoration of this war? Do the British as a nation need ‘closure’ now on World War I?

I cannot answer all these questions, but I shall attempt to allude to them all.

* * *

As Santanu Das’s book Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature (2005) examines so admirably, the terrible, Apocalyptic worlds of the Western Front and Gallipoli were themselves almost unbearably ‘touchy and feely’. I suggest that we all ‘know’ this, by which I mean we have already ingested deep into our psyches not only the images of mud, corpses and no man’s land, but this context of human intimacy in extremis.

Perhaps this is why it is so often small, even trivial, personal details that can trigger in us such unwithstandable emotion. Archivists work in archives with papers covered in words, but as Das himself says, the stains of trench mud on a letter and ‘a bunch of blue and white flowers, the dried stalks still green pressed onto the letter’ — the ‘material tokens of memory’ — are almost too ‘intimate and unsettling’. The fact that ten-year-old Lesbia Corbet had already tried on her bridesmaid’s dress for her brother Jim’s wedding when he was killed at Givenchy (see my posts of 15 and 17 April) is of a similar order; or George’s arachnophobia as shells are flying overhead at Gallipoli. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission is currently tweeting inscriptions on gravestones: ‘I’m all right mother cheerio’ is a fair example of how overwhelming their brevity and authenticity can be.

These small things instantly transport us to the reality of the person and his/her predicament linked to the War; simultaneously they access all we know and feel about the tragedy of World War I; and it is often far too much to bear. I think initially, as one holds the letter with the pressed flowers, say, or reads the living inscription, one’s feelings are akin to grief and bereavement, because one momentarily feels one knows that person. But one also knows they were killed next day, or their women’s and families’ lives destroyed, and those are the ‘impossible’ facts that can engulf one. In a word, I think that what commemoration in 2015 does, whether in the form of a service, or heart-rending biographies of the fallen, or the reading of war poetry, or the viewing of personal items in glass cases at an exhibition, is make us re-experience to the full the pity of war.

Where the blog is concerned, I think it is also the pity of George and Kittie’s lives that followers, and I, sometimes find too much. There is no space here to define or analyse this ‘pity’, or what Wilfred Owen meant by ‘the pity of war’, but I do not think that is necessary.

* * *

I happen to believe it is our own empathy that enables us to be so moved by these small items or details, or aspects of commemoration, and I believe that there has been an enormous increase in the recognition, understanding and cultivation of empathy in Britain in the last thirty years or so. Europeans and North Americans remark on it. We increasingly believe that ‘feeling into’ a person’s situation is vital to our emotional understanding of them and to our own ’emotional intelligence’ (a phrase, incidentally, that George was one of the first to use in print, in 1911). Surely this is a good thing?

Kierkegaard wrote: ‘The majority of men are subjective towards themselves and objective towards all others, terribly objective at times — but the real task is in fact to be objective towards oneself and subjective towards all others.’ That is true empathy. But obviously, if our empathy is restricted to ‘putting ourselves in other people’s shoes’ and feeling and thinking what we would experience in those shoes, it risks being about ourselves rather than others. The possibility is always there that our pity is merely a rush of self-pity.

* * *

We certainly have become more ‘tearful’ as a nation, but I think one reason is that society has become theatricalised almost to saturation. Crimes, disasters, public inquiries, very recent political history, are instantly translated to the television screen, the computer screen, film or the stage. Bizarrely — to older generations — an historical event like Waterloo is no longer just commemorated, it has to be ‘enacted’ (not ‘re-enacted’), and the media even talk of ‘Napoleon’ or ‘Wellington’ when they mean the actors impersonating them. We are invited by the media to respond to real events as theatrical performances. Above all, we are an instantly self-imaging society. We are therefore more used than ever to responding to a third term: the imaged, quasi-dramatic representation of people and events, rather than the individuals and the events themselves. Within hours of a disaster anywhere in the world, we can watch ‘footage’ of it and emote about it. In May 1915 Britons had a newspaper with one archive photograph of the Lusitania on its front page.

If the paradigm of our twenty-first-century empathy is theatre, can we learn anything from the experience and tradition of audience empathy in the real theatre?

Possibly. I have said already that I think our powers of genuine empathy access the ‘tragedy’ of the War, and if by that we mean something complexly, unbearably ineluctable, then those feelings are akin to the fear and pity of the greatest tragic plays.

In that context, Aristotle’s concept of ‘catharsis’ might look applicable. Unfortunately, theatrical catharsis is most commonly thought of as ‘purifying’, ‘purging’, getting rid of the strongest emotions we are capable of through empathy in the theatre. It is true, I believe, that the notion of bowel evacuation or surgical bleeding is present in Aristotle’s original concept. But how can this help us in coming to terms with the tragedy of the fallen in World War I? It seems too much as though it is designed to produce anaesthesia; a ‘closure’ and ‘return to equanimity’ indistinguishable, perhaps, from indifference.

In truth I don’t believe theatrical catharsis is about an audience getting rid of visceral emotions, it is about these emotions enabling us to face what we are seeing on the stage and know exists in real life. In this sense, there can be comic as well as tragic catharsis. I believe a fragment of Mikhail Bakhtin’s expresses theatrical catharsis more accurately: ‘Tragedy and laughter look being in the eyes equally fearlessly, they do not construct any illusions, they are sober and exacting.’ Nadezhda Mandel’shtam also made a vital distinction, when she said that ‘genuine tragedy is rooted in an understanding of the nature of evil, and only that tragedy can bring us catharsis’. If our empathetic response to the commemoration and ‘material tokens of memory’ of World War I helps us to look being and evil in the eyes fearlessly, to dispense with all illusion about this human tragedy, then perhaps catharsis is the right word for what we are going through in these four years.

* * *

It is interesting that psychologists use the word ‘catharsis’ in the sense of ‘the purging of the effects [my italics] of pent-up emotion and repressed thoughts, by bringing them to the surface of consciousness’ (Chambers). On ‘the surface of consciousness’, presumably, they are more likely to be cognitively, intellectually, rationally understood — and their sources faced. I therefore think that the identity with theatrical catharsis, if we accept Bakhtin’s and Nadezhda Mandel’shtam’s descriptions of it, may hold.

The point is, empathy is not an end in itself. I have always felt that the limits of empathy must be understanding. You ‘feel in’, you must attempt to be fully ‘subjective’ to others, but this is the beginning of a process. The process should be towards understanding, indeed ‘knowing’ — not knowing in a closed-off sense, but a rational knowing that is momentarily at rest and secure, that ‘looks being in the eyes fearlessly’, perhaps. It is a process that should lead to knowledge and intelligent action.

Are there people who are capable of great empathy but refuse to reach beyond it? I would say that the personal life of the late Princess of Wales, who is often credited with our ‘discovery’ of empathy as a nation, suggests there are. I have also had colleagues with superb powers of emotional understanding, but who felt no need to use them to help students actually solve their problems.

* * *

If the effect of an empathetic response is true cathartic understanding, I see no reason why there is anything wrong, harmful or dangerous about repeating the experience. We do not suggest that seeing one Agamemnon or King Lear is enough. All the time we have an authentic empathetic response to the ‘tokens of memory’ of the War, we are learning. I see no reason why we cannot sustain our emotional response to it for four years if that emotional response is always pure, ‘exacting’, committed to cathartic understanding, and does not degenerate into self-indulgence. I admit that empathy can be exhausting, but our gains in understanding of the tragedy that was the War can be immense.

The Sirens of sentiment, though, lie always in wait. The concept of ‘tragic pleasure’ has always been a dubious one, and we all know how easy it is to fall into enjoying strong feelings. The more they are repeated, the greater the temptation to become addicted to them. Again, I think the blanket theatricalisation of our lives encourages that: we are asked to respond physically to all the media spectacles around us and we end up always crying, or always demonstratively sweeping the (sometimes non-existent) tears from the corners of our eyes like, well, bad tragedians.

* * *

In fine, the conversation is about authentic empathy and its surrogate, sentiment. We associate sentimentality more with the Victorians than the Edwardians, so Laurence Binyon’s words to Kittie about his memorial ode to George (see my post of 25 June) are all the more interesting. Here is the author of the most quoted and, many would say, most emotionally churning poem to come out of the First World War, drawing back from emotionality because of what George was: ‘I wanted to be as exact as I could, and the thought of him cannot be anything but tonic, an astringent to sentiment.’ It is a salutary reminder, a warning against the pleasurable emotional response to the Last Post or ‘For the Fallen’; an astringent from George Calderon himself.

* * *

‘Closure’ has been defined as ‘the evolution of emotions to make them more stable and bearable’ and, less positively, as ‘a feeling of satisfaction or resignation when a particular episode has come to an end’ (Chambers).

It would be interesting indeed to hear the response of ‘professional’ psychologists, psychotherapists and bereavement counsellors to the conversation about this subject that we Calderonians and blog followers have had over the last year and which I have endeavoured to display above. However, I believe that we all have a right as ‘amateur’ psychologists yet full-time human beings, to present our take on it.

I have to say that I meet very few people in the theatre who believe in ‘closure’. This is probably because their life’s work is with empathy, emotions, and the expression of them. They rely on their emotional memory being open and accessible. They cannot just ‘close off’ those sources of their lives as actors or directors. It would be self-destructive. It would be to deny the existence, the goodness, of those sources.

Similarly, I feel that the tragedy of the First World War, for nations and for individuals, is so immense and so important to us that we should never seek ’emotional closure’ on it, just as a German president has said that for his nation there can never be ‘moral closure’. We always need our empathetic response to the fallen, and to the survivors, in order to relate to them fully as human beings. To remember them emotionally is the most human form of memory. We need to do this forever, in order to understand the lessons of this War and, I believe, to keep renewing ourselves as a nation.

I am especially grateful to Clare Hopkins, Archivist of Trinity College, Oxford, for her extended contributions over the past year to the conversation about Commemoration. (Click here for a comment by Clare with her thoughts on the subject.)

Next entry: Letter from Alexandria