The Imperial War Museum invited me to contribute a post to their Research Blog, and I promptly accepted. I am not, of course, a military historian, and when I started researching the last ten months of George’s life I was expecting to have to travel to and fro to London for weeks to research the Third Battle of Krithia in the IWM’s archives. Not so! I found all the leads and materials I was looking for online, as the Museum’s holdings are superbly catalogued. There were pointers to the specialist literature, even a paper on the Third Battle of Krithia produced by the IWM itself, there were copious photographs (including the spectacular one I reproduced on 4 June), there were artefacts, and I was able to correspond with an in-house expert on Gallipoli. Taking all that together with my own reading of the classic works on Gallipoli, and the three eye-witness accounts of 4 June in Kittie’s possession, I thought I had everything I needed to describe what happened. I based my guest post, therefore, more or less on what I have just said in this paragraph.

But the Museum was concerned that I had not actually worked on any archival material in the building. How right, in the event, they were. I volunteered to go up there ten days ago to look at the papers of the 1st KOSB’s commanding officer at the battle; the war diary of Reeves, the man who shared a cabin with George on the Orsova and was also then attached to the 1st KOSB on the peninsula; a long letter from Jack Harley, a Trinity (Oxford) man ten years younger than George, to whom Clare Hopkins, Trinity’s Archivist, had kindly drawn my attention; and for good measure the war diary of the extraordinary survivor Sergeant-Major Daniel Joiner. I say ‘for good measure’, as Joiner’s diary is copiously quoted by Peter Hart in his Gallipoli (2013) and I couldn’t believe there would be anything in it about the Third Battle of Krithia that he hadn’t reproduced already, but the diary is so vivid and gripping that I couldn’t resist having a read of the original anyway.

I have been pondering the results of this visit to the IWM ever since.

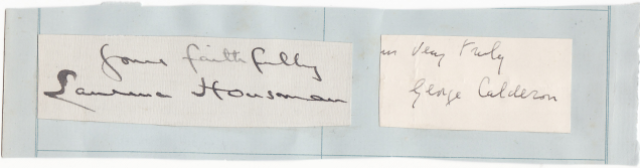

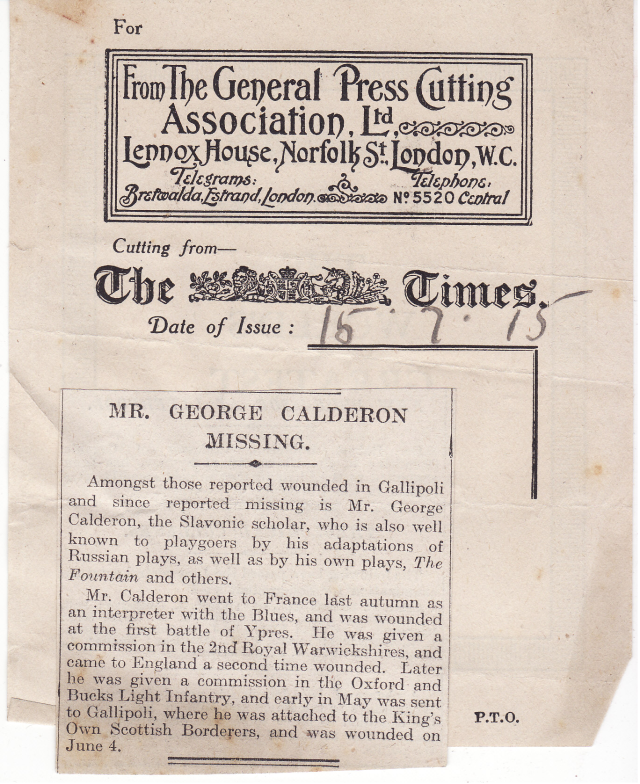

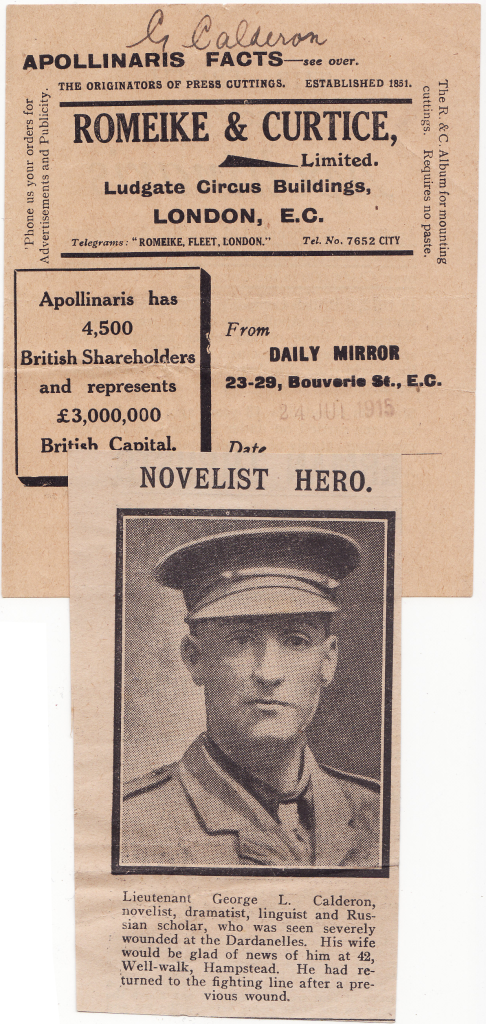

The papers of Major G.B. Stoney, the 1st KOSB’s CO on 4 June 1915, refer to some events described by George in his letters to Kittie, but they do not refer to George by name. 2nd Lieutenant R.M.E. Reeves refers to George being sea-sick on the night of 12 May, like most of the officers, and to sharing a dugout with ‘Calderon’ on the night of 27 May. There is circumstantial evidence in Lieutenant Jack Harley’s letter to his father that he knew George, but no mention of him by name. On p. 243 of Gallipoli Peter Hart quotes Joiner’s account of attacking with C Company on 4 June and taking four trenches.

The really important thing, however, is that although Stoney did not describe the battle at all and Harley was killed in it at the same time as George, Reeves and Joiner did survive it and did describe the whole course of the KOSB’s experience of it on that day, 4 June 1915. Their descriptions diverge from the Official History, and even from Captain Pat(t)erson’s eye witness account presented to Kittie, and they diverge in significant ways.

2nd Lieutenant Reeves, a solicitor perhaps in his late twenties, commanded 14 Platoon of the 1st KOSB. This meant he was in D Company, which was led by Captain Hogan and technically in reserve. George Calderon commanded 8 Platoon in B Company, which was led by Captain Grogan. The Official History, Capt. Pat(t)erson, and books about Gallipoli, talk of two waves of attack, the first at 12.00 consisting of A and B Companies, the second timed for 12.15 consisting of C and D. Naturally, one makes the assumption that in each wave the two companies went over the top simultaneously. However, Reeves says ‘A and B Companies attacked and lost very heavily’ and makes it quite clear that C then went in on its own (presumably in ‘platoon rushes’ as Pat(t)erson puts it), and finally D on its own. Reeves, incidentally, as well as being injured was traumatised by what he saw in the battle and is the only source I (now) know for the precise figure of the 1st KOSB’s losses: ‘Our casualties since Friday [4 June] at 12 p.m. are 19 officers and 432 killed, wounded and missing’ (i.e. probably half the battalion).

Quartermaster Sergeant-Major Joiner was with C Company. He makes it quite clear that the companies went over the top separately — in fact he does not even use the word ‘waves’. ‘A Coy. mounted the ladders ready for the stroke of 12’, he writes, ‘but instead of going forward, either fell back again wounded or killed. The majority in fact hardly got their heads over the parapet.’ This was because ‘on the stroke of 12 [the Turkish machine guns] opened fire right along the top of our parapet.’ To Joiner this seemed such a coincidence that he concluded the enemy knew the plan of attack (Peter Hart advises me to ‘disregard this speculation’). Joiner continues: ‘B Coy. now jumped, they also suffered, and the fate of our individual attack hung in the balance for a few seconds.’ Admittedly Joiner must be wrong to state that ‘everything from the stroke of 12 until we (C Coy.) had joined in the attack was but a few seconds’, because Pat(t)erson as Adjutant directing half of the attack surely knew what he was talking about when he said Stoney waited half an hour before launching the second wave; but equally Joiner must be right to describe A and B Companies as going over the top separately. Moreover, here Joiner’s account squares with Sergeant-Major Allan’s account taken down in hospital in Alexandria by Mrs Ludolf (see my post of 13 July). On the basis of Reeves and Joiner’s war diaries, I conclude that when Allan spoke of ‘two lines’ of attack, and of George being in the second, he was referring to the fact that the two companies, A and B, went over the top consecutively and not as a single, simultaneous ‘first wave’.

So how does this change our picture of George Calderon going to his death?

Instead of the image of him leading his platoon forward with the customary shout in one long line of two companies constituting the ‘first wave’, we have the image of A Company being slaughtered and wounded on his right before his very eyes, in many cases before leaving the front trench, and then, with the rest of B Company, having to summon the courage to take their place… In a word, the situation when George had to go over the top was even worse than I imagined. According to these war diaries, by now the trenches (which were more like ‘sangars’ and only four foot six deep) were beginning to collapse and the scaling ladders could not be used. As it happens, B Company were luckier than A Company, but still there is no reliable evidence that any reached the first Turkish trench. When C Company attacked, Joiner writes, the ground was already ‘littered with dead’.

The end of my post of 4 June 2015 will have to be rewritten. The photograph that illustrates it must be of C or D Company going over the top, as there are no wounded or dead visible. The map is still accurate to the best of our information. Hogan is described by Reeves as wounded, together with Lieutenants Deighton and Thompson of D Company, and I am not at all surprised, after reading Reeves’s account, that Hogan should not know the fate of George forty minutes earlier. Also, one can well understand why, in the absence of evidence that George himself was wounded or reported killed, Hogan thought he might have been captured.

* * *

Where does all this leave us?

There is a clear discrepancy between the official and officers’ accounts AND the personal and privates’ accounts of the 1st KOSB’s action at noon on 4 June 1915. But this is not to say that the first set of accounts wilfully distort or sanitise the facts. Their ‘perspective’ is simply different. Given the length of the Official History of the Gallipoli campaign, it is understandable that the facts should be somewhat compressed. On the other hand, it was fixed in the tabulated order of battle (see my post of 4 June) that there would be two ‘waves’, one at 12.00 and the other at 12.15, and it is tempting to think that the official and officers’ accounts wanted to believe the orders had been rigidly followed. Thus although Captain Pat(t)erson was present as the 1st KOSB’s Adjutant directing half the forces, the way he thought about what he witnessed may have been pre-set by his orders.

However, we are also dealing here with two distinct chronotopes — ways of presenting time. The Official History is, by definition, an historical narrative: a tight nexus of events presented within a longish sweep of time (two years). For that purpose it is natural for certain details and complications to fall away. I would suggest there was a tendency among officers to see events more historically, too. Perhaps the higher up the military ladder you were at Gallipoli, the more you saw events with ‘helicopter vision’ (and the more unmoved you were by the casualty figures). It is, of course, implicit in the historical chronotope and mindset to see events as past (cf. the lady in my ‘Dialogue’ of 18 July).

By contrast, NCOs Joiner and Allan, and 2nd Lieutenant Reeves, present personal time, discrete from historical time; their accounts are limited to the small segments of time that they experienced. They actually waited for their turn to go over the top, they did go over the top, whereas Stoney and Pat(t)erson only observed and followed when it was safe. In terms, then, of the synchronic reality of the battle for the 1st KOSB — what it looked like and felt like to attack ‘in the present’ — Joiner’s, Allan’s and Reeves’s accounts are more authentic, or more emotional and, dare one say it, more empathetic. According to their accounts, it wasn’t a case of two ‘waves’ storming forwards on cue with hurrahs and officers waving revolvers and walking sticks, it was a horrific mess left on or in the trenches. Two companies, A and B, walked at an interval into walls of lead and the fate of the 1st KOSB’s attack hung in the balance until Stoney actually postponed it by twenty minutes and the progress made by the troops to left and right of them enabled C and D Companies to carry the day.

Yet again we are discussing Time. What I have called ‘tourbillions in Time’ — starting halfway in, flashbacks, flashes forward, ‘greater time, lesser time’, different ways of looking at time — sweep through my biography of George Calderon. There is no space here to discuss whether our brains are programmed to think of time in various ways, or whether these ways are simply cultural constructs (Stone Age, Greek, Aztec, Buddhist, historical, Einsteinian…). I will, though, conclude by touching on one form of time that has always been at the heart of this blog. Do we sometimes think of time circularly simply because of the cycle of the year? Why do we ‘re-experience’ events at their anniversaries? Why have I been able to claim right from the start of this blog that it tells George and Kittie’s life ‘in real time’, when in fact that merely means ‘as it happened exactly 100 years ago’?

* * *

Note. The phrase ‘tourbillions in Time’ is taken from Robert Graves’s lyric ‘On Portents’.

Next entry: 21 July 1915

Flashback — and tourbillions in Time (again)

The Imperial War Museum invited me to contribute a post to their Research Blog, and I promptly accepted. I am not, of course, a military historian, and when I started researching the last ten months of George’s life I was expecting to have to travel to and fro to London for weeks to research the Third Battle of Krithia in the IWM’s archives. Not so! I found all the leads and materials I was looking for online, as the Museum’s holdings are superbly catalogued. There were pointers to the specialist literature, even a paper on the Third Battle of Krithia produced by the IWM itself, there were copious photographs (including the spectacular one I reproduced on 4 June), there were artefacts, and I was able to correspond with an in-house expert on Gallipoli. Taking all that together with my own reading of the classic works on Gallipoli, and the three eye-witness accounts of 4 June in Kittie’s possession, I thought I had everything I needed to describe what happened. I based my guest post, therefore, more or less on what I have just said in this paragraph.

But the Museum was concerned that I had not actually worked on any archival material in the building. How right, in the event, they were. I volunteered to go up there ten days ago to look at the papers of the 1st KOSB’s commanding officer at the battle; the war diary of Reeves, the man who shared a cabin with George on the Orsova and was also then attached to the 1st KOSB on the peninsula; a long letter from Jack Harley, a Trinity (Oxford) man ten years younger than George, to whom Clare Hopkins, Trinity’s Archivist, had kindly drawn my attention; and for good measure the war diary of the extraordinary survivor Sergeant-Major Daniel Joiner. I say ‘for good measure’, as Joiner’s diary is copiously quoted by Peter Hart in his Gallipoli (2013) and I couldn’t believe there would be anything in it about the Third Battle of Krithia that he hadn’t reproduced already, but the diary is so vivid and gripping that I couldn’t resist having a read of the original anyway.

I have been pondering the results of this visit to the IWM ever since.

The papers of Major G.B. Stoney, the 1st KOSB’s CO on 4 June 1915, refer to some events described by George in his letters to Kittie, but they do not refer to George by name. 2nd Lieutenant R.M.E. Reeves refers to George being sea-sick on the night of 12 May, like most of the officers, and to sharing a dugout with ‘Calderon’ on the night of 27 May. There is circumstantial evidence in Lieutenant Jack Harley’s letter to his father that he knew George, but no mention of him by name. On p. 243 of Gallipoli Peter Hart quotes Joiner’s account of attacking with C Company on 4 June and taking four trenches.

The really important thing, however, is that although Stoney did not describe the battle at all and Harley was killed in it at the same time as George, Reeves and Joiner did survive it and did describe the whole course of the KOSB’s experience of it on that day, 4 June 1915. Their descriptions diverge from the Official History, and even from Captain Pat(t)erson’s eye witness account presented to Kittie, and they diverge in significant ways.

2nd Lieutenant Reeves, a solicitor perhaps in his late twenties, commanded 14 Platoon of the 1st KOSB. This meant he was in D Company, which was led by Captain Hogan and technically in reserve. George Calderon commanded 8 Platoon in B Company, which was led by Captain Grogan. The Official History, Capt. Pat(t)erson, and books about Gallipoli, talk of two waves of attack, the first at 12.00 consisting of A and B Companies, the second timed for 12.15 consisting of C and D. Naturally, one makes the assumption that in each wave the two companies went over the top simultaneously. However, Reeves says ‘A and B Companies attacked and lost very heavily’ and makes it quite clear that C then went in on its own (presumably in ‘platoon rushes’ as Pat(t)erson puts it), and finally D on its own. Reeves, incidentally, as well as being injured was traumatised by what he saw in the battle and is the only source I (now) know for the precise figure of the 1st KOSB’s losses: ‘Our casualties since Friday [4 June] at 12 p.m. are 19 officers and 432 killed, wounded and missing’ (i.e. probably half the battalion).

Quartermaster Sergeant-Major Joiner was with C Company. He makes it quite clear that the companies went over the top separately — in fact he does not even use the word ‘waves’. ‘A Coy. mounted the ladders ready for the stroke of 12’, he writes, ‘but instead of going forward, either fell back again wounded or killed. The majority in fact hardly got their heads over the parapet.’ This was because ‘on the stroke of 12 [the Turkish machine guns] opened fire right along the top of our parapet.’ To Joiner this seemed such a coincidence that he concluded the enemy knew the plan of attack (Peter Hart advises me to ‘disregard this speculation’). Joiner continues: ‘B Coy. now jumped, they also suffered, and the fate of our individual attack hung in the balance for a few seconds.’ Admittedly Joiner must be wrong to state that ‘everything from the stroke of 12 until we (C Coy.) had joined in the attack was but a few seconds’, because Pat(t)erson as Adjutant directing half of the attack surely knew what he was talking about when he said Stoney waited half an hour before launching the second wave; but equally Joiner must be right to describe A and B Companies as going over the top separately. Moreover, here Joiner’s account squares with Sergeant-Major Allan’s account taken down in hospital in Alexandria by Mrs Ludolf (see my post of 13 July). On the basis of Reeves and Joiner’s war diaries, I conclude that when Allan spoke of ‘two lines’ of attack, and of George being in the second, he was referring to the fact that the two companies, A and B, went over the top consecutively and not as a single, simultaneous ‘first wave’.

So how does this change our picture of George Calderon going to his death?

Instead of the image of him leading his platoon forward with the customary shout in one long line of two companies constituting the ‘first wave’, we have the image of A Company being slaughtered and wounded on his right before his very eyes, in many cases before leaving the front trench, and then, with the rest of B Company, having to summon the courage to take their place… In a word, the situation when George had to go over the top was even worse than I imagined. According to these war diaries, by now the trenches (which were more like ‘sangars’ and only four foot six deep) were beginning to collapse and the scaling ladders could not be used. As it happens, B Company were luckier than A Company, but still there is no reliable evidence that any reached the first Turkish trench. When C Company attacked, Joiner writes, the ground was already ‘littered with dead’.

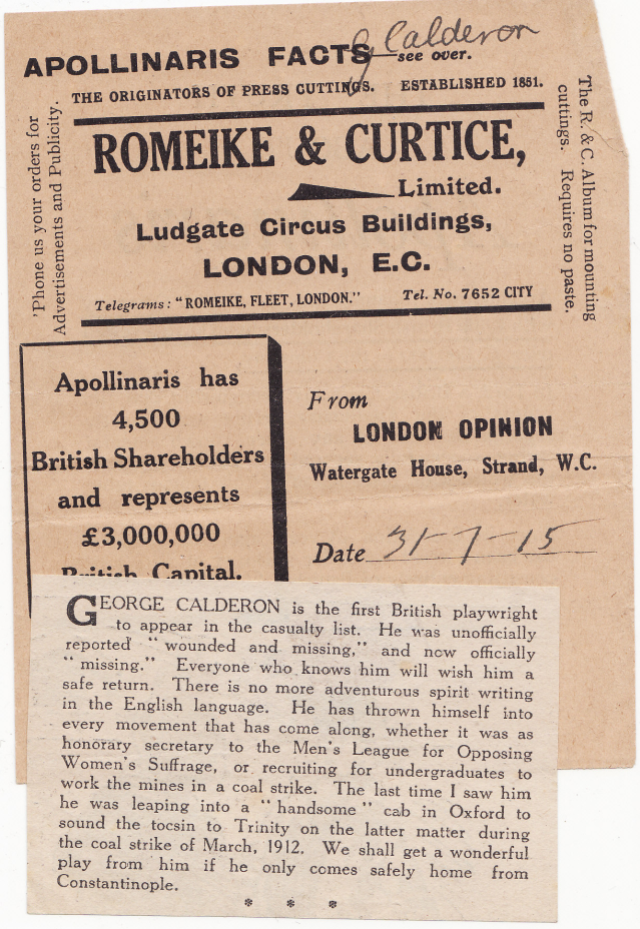

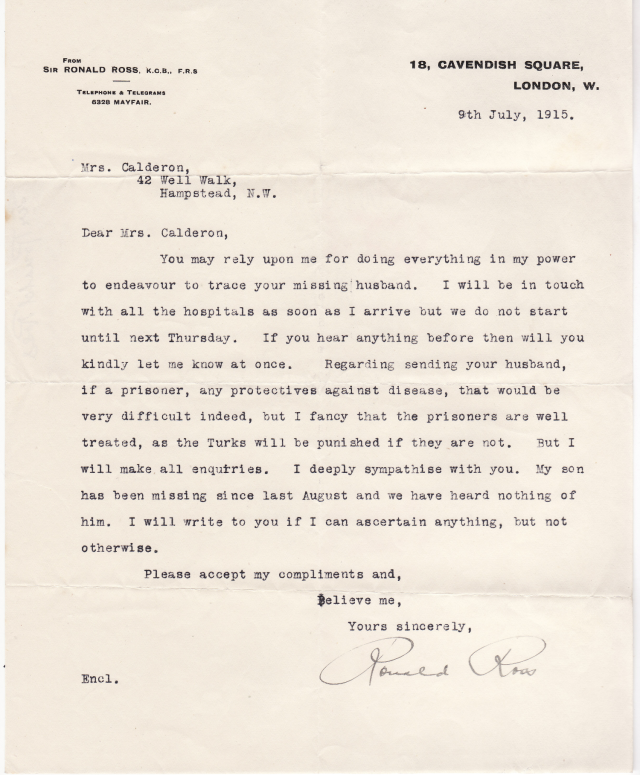

The end of my post of 4 June 2015 will have to be rewritten. The photograph that illustrates it must be of C or D Company going over the top, as there are no wounded or dead visible. The map is still accurate to the best of our information. Hogan is described by Reeves as wounded, together with Lieutenants Deighton and Thompson of D Company, and I am not at all surprised, after reading Reeves’s account, that Hogan should not know the fate of George forty minutes earlier. Also, one can well understand why, in the absence of evidence that George himself was wounded or reported killed, Hogan thought he might have been captured.

* * *

Where does all this leave us?

There is a clear discrepancy between the official and officers’ accounts AND the personal and privates’ accounts of the 1st KOSB’s action at noon on 4 June 1915. But this is not to say that the first set of accounts wilfully distort or sanitise the facts. Their ‘perspective’ is simply different. Given the length of the Official History of the Gallipoli campaign, it is understandable that the facts should be somewhat compressed. On the other hand, it was fixed in the tabulated order of battle (see my post of 4 June) that there would be two ‘waves’, one at 12.00 and the other at 12.15, and it is tempting to think that the official and officers’ accounts wanted to believe the orders had been rigidly followed. Thus although Captain Pat(t)erson was present as the 1st KOSB’s Adjutant directing half the forces, the way he thought about what he witnessed may have been pre-set by his orders.

However, we are also dealing here with two distinct chronotopes — ways of presenting time. The Official History is, by definition, an historical narrative: a tight nexus of events presented within a longish sweep of time (two years). For that purpose it is natural for certain details and complications to fall away. I would suggest there was a tendency among officers to see events more historically, too. Perhaps the higher up the military ladder you were at Gallipoli, the more you saw events with ‘helicopter vision’ (and the more unmoved you were by the casualty figures). It is, of course, implicit in the historical chronotope and mindset to see events as past (cf. the lady in my ‘Dialogue’ of 18 July).

By contrast, NCOs Joiner and Allan, and 2nd Lieutenant Reeves, present personal time, discrete from historical time; their accounts are limited to the small segments of time that they experienced. They actually waited for their turn to go over the top, they did go over the top, whereas Stoney and Pat(t)erson only observed and followed when it was safe. In terms, then, of the synchronic reality of the battle for the 1st KOSB — what it looked like and felt like to attack ‘in the present’ — Joiner’s, Allan’s and Reeves’s accounts are more authentic, or more emotional and, dare one say it, more empathetic. According to their accounts, it wasn’t a case of two ‘waves’ storming forwards on cue with hurrahs and officers waving revolvers and walking sticks, it was a horrific mess left on or in the trenches. Two companies, A and B, walked at an interval into walls of lead and the fate of the 1st KOSB’s attack hung in the balance until Stoney actually postponed it by twenty minutes and the progress made by the troops to left and right of them enabled C and D Companies to carry the day.

Yet again we are discussing Time. What I have called ‘tourbillions in Time’ — starting halfway in, flashbacks, flashes forward, ‘greater time, lesser time’, different ways of looking at time — sweep through my biography of George Calderon. There is no space here to discuss whether our brains are programmed to think of time in various ways, or whether these ways are simply cultural constructs (Stone Age, Greek, Aztec, Buddhist, historical, Einsteinian…). I will, though, conclude by touching on one form of time that has always been at the heart of this blog. Do we sometimes think of time circularly simply because of the cycle of the year? Why do we ‘re-experience’ events at their anniversaries? Why have I been able to claim right from the start of this blog that it tells George and Kittie’s life ‘in real time’, when in fact that merely means ‘as it happened exactly 100 years ago’?

* * *

Note. The phrase ‘tourbillions in Time’ is taken from Robert Graves’s lyric ‘On Portents’.

Next entry: 21 July 1915