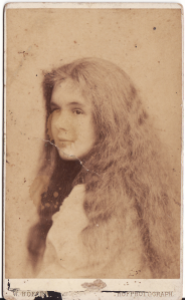

17/09/15. We have had a wobble of excitement this week. An advertisement appeared in AbeBooks entitled ‘Calderon, Lieut George Leslie — Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry — an Original Photographic Portrait […] printed circa 1919’. Sensational! The implication was that it was a studio portrait of George taken in his Ox & Bucks uniform, perhaps before embarking for Gallipoli. Not only would this have been the first such portrait to have come to light, it might have told us something about his physical condition in May 1915, a subject much speculated upon. I was sceptical, though, because there is no such photograph in Kittie’s collection and one might have thought she would have used it in Percy Lubbock’s George Calderon: A Sketch from Memory in preference to the ghastly ‘dead-eyed’ one of George in insignia-less uniform as an Interpreter in October 1914 (see the banner to this website).

Unfortunately, the photograph advertised in AbeBooks is actually the familiar 1914 one after all. Mr Barrie Kaye, of KBooks, who are selling the portrait ‘mounted and ready to frame’, kindly sent me a scan and incidentally explained that the portrait came from a seven-volume Memorial to Rugbeians killed in WW1, which was produced in 1919. This was in itself interesting, as I researched and wrote my chapter on George at Rugby long ago and was not aware of this publication. Apparently, as well as a photograph there is a page or two on each of Rugby’ s war dead, describing their school life and war services (which would, of course, specify his commission as being with the Ox & Bucks). I had better have a look at this publication. l am grateful to Mr Kaye for telling me about the

Memorial, and I see that the photograph is still available through AbeBooks.

If you haven’t read the latest cracker of a Comment from Clare Hopkins, I recommend that you do (top right)…and contribute to the discussion! Clare is absolutely right that in ‘laying out George and Kittie’s daily lives’ I have invited readers to ‘subject an Edwardian character to 21st century scrutiny’ . I think this is fruitful. It is one major reason why I am writing the biography.

(By the way, my chapter on George’s opposition to women’s suffrage is available on my website at ‘Recent Writing’.)

Katy George has emailed me with some very interesting observations on this device that Kittie Calderon designed for the cover of Percy Lubbock’s book about George and all the subsequent Volumes of George’s works:

I had suggested, based on Edwardian emoticons used in letters, that the two intersecting circles were George and Kittie, the letters perhaps stood for ‘George’ and ‘Catherine’ as well as ‘George Calderon’, and that the ear of barley referred to Christ’s words ‘except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit’. However, this doesn’t explain why it is an ear of barley and not wheat (and we know from Percy Lubbock’s correspondence with Kittie that it is barley).

Katy has suggested that the barley is a reference to Robert Dwyer Joyce’s ballad ‘The Wind That Shakes the Barley’ — and I find this very plausible for two reasons. First, the ear is still a symbol of immortality because in the ballad the barley springs up every year on the graves of the Irish rebels who carried grains in their pockets as food but who, like George, also died for their country and left their loved ones in order to fight. Second, Kittie was born and brought up in Ireland, was a member of the Irish Literary Society, and I think we can presume that she knew Joyce’s ballad.

Katy has also suggested that the circles might be ‘mandorlas’. If you Google on ‘mandorla’, you will discover what a rich subject this is. I am not myself convinced that the circles in Kittie’s design are mandorlas in the religious sense (roughly, two haloes enclosing a figure, e.g. the Virgin Mary). Nor, clearly, are they examples of the most famous geometrical form of mandorla, the vesica piscis, as their perimeters do not pass through each other’s centres. However, in effect the circles on the book cover are a form of the latter. Perhaps, quite simply, they symbolise George and Kittie’s (larger and smaller) wedding rings. Whichever, I am extremely grateful to Katy for her stimulating contribution.

One of the subjects I have had to delve into more deeply in order to write my next (and penultimate) chapter, is the whole Arts and Crafts movement. it is clear to me now — from the interior furnishing of her home with Archie Ripley, through the Brasted artistic community, to the very firm that produced the blocks for illustrations in Percy

Lubbock’s Sketch — that since being an art student Kittie had always moved in the A&C swim. Even George, despite his conservative cast of mind, held views about craftsmanship and manual labour reminiscent of William Morris.

A fascinating new biography has just come out, Amazing Grace: The Man Who Was WG, by Richard Tomlinson. It is a biography after my own heart, because it not only presents the fullest account of Grace’s life to date, but has an overriding theme: the ‘amateur’ (i.e. ‘gentleman’)/ ‘professional’ divide in cricket which led to ‘shamateurisrn’ and in the words of Guardian reviewer Peter Wilby ‘turned English cricket into a joke from which it has never quite recovered’. This is an Edwardian subject, of course, and crops up periodically in my biography because Calderon believed in the ‘amateur’ both on the cricket field and in his many other life pursuits. However, the theme of my own book could perhaps best be summarized in a new title such as George Calderon: The Case For Edwardian Genius.

As always, if you have any ideas about plausible publishers, please email them me through my Website http://patrickmiles.co.uk. Thank you for reading!

Watch this Space

25/9/15. A natural consequence of turning the blog into a Website is that no-one (it seems!) wants to leave a Comment, because visitors who followed it every day last year no longer have a reason for looking in, and casual viewers now (of whom there are a decent number from all over the world) don’t, presumably, feel they know enough to ‘opinionate’. The casual viewers, incidentally, have usually just zoomed in for a post that has something

on their Google search term, e.g. Chekhov translations, Tahiti, Rabindranath Tagore, Michel Fokine or the Third Battle of Krithia.

I had hoped that by taking down my own brief response to Clare Hopkins’s superbly provocative last Comment top right I might encourage other people to weigh in. And everyone is still welcome and encouraged to do that! However, I appreciate that Clare’s Comment does draw on the whole gamut of last year’s posts — is very comprehensive — so people zooming in and out may not feel they are qualified to Comment on it… Personally, I don’t think that should put anyone off, but I know from their emails that many loyal ‘Calderonians’ also feel they have no more to say.

So I am going to leave the hall in other people’s courts for another week, before I attempt a reply to Clare myself, which she has certainly earned. The reply should be comprehensive, of course. It will be just like old times! Depending on what happens after that, I may ask my blogmaster to ‘archive’ the Comments so that viewers can read them all.

I think we have more or less exhausted the subject of what the device stands for that Kittie designed for the Arts and Crafts covers of Percy Lubbock’s George Calderon: A Sketch from Memory and George’s selected works, but I think it is so attractive that I am going to leave it here a bit longer. It will then join our Gallery at the right. A close inspection indicates, incidentally, that the gold really contains gold.

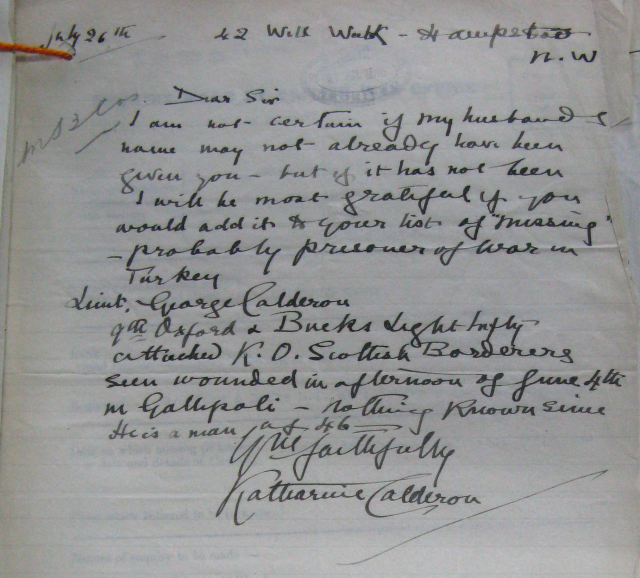

I am glad to report that the writing of the penultimate chapter of my biography of George, ‘Aftermath and Masterpiece’ [Kittie 1915-22] is going very well. I am hopeful that readers will have benefited from my difficulties with ‘chronotopia’, which gave me much longer to think about this chapter before writing it than would have been the case had I not been running the blog. I believe I have a far better understanding of Kittie’s life after 4 June

1915 than I would have had otherwise.

I always have four or five approaches to publishers in the air, hut if you have any ideas about plausible publishers yourself, please don’t hesitate to email them me through my Website http://patrickmiles.co.uk. Thank you for reading!