This page contains archived ‘Watch this Space’ posts, with the most recent first.

Watch this Space 19 May 2016

19/5/16. Putting them all together, the number of themes that my consultants (see previous post below) feel should be addressed in my Introduction is considerable; impractically so. I have spent some time, therefore, working out the overlap and identifying what they see as the core substance that must go in. I have completely recast the Introduction in my head, written what I think is a strong beginning, and words are beginning to present themselves for the rest. But I keep rearranging the themes mentally, dipping into the introductions of brilliant recent biographies, pursuing all kinds of ideas. I am determined to keep an open mind about this for a week or two longer. I am in no hurry with it, already have my doubts about the ‘strong beginning’, and know I shall have to let the new Introduction lie for a month or so after I have finished it… Perhaps it will then go the way of the first two drafts. But surely it will be an improvement on them?

It would be reasonable to ask why I don’t just write what I want to write. The answer is in what I said in my last post about things that ‘bug’ the writer rather than address and interest the reader. Examples of the former in my case would be (a) my obsession with all the people who over the years have said to me ‘George Calderon? Never heard of him!’ and frankly told me I was wasting my time, (b) the delicate question of the ‘tourbillions of time’ in my biography, i.e. the non-linear way I am telling it, and (c) the fact that it is a biography of Kittie and the whole Calderon set as well as principally of George.

I’m encouraged that several of my consultants — all of whom have read at least one chapter — feel I do have to tackle (a). None of them has mentioned (b) and (c). But I must at least touch on (b) and (c) in the Introduction, as they are aspects that readers need warning about; they are risks that I have taken in the book.

In that connection, I am encouraged by something that Ruth Scurr wrote in The Guardian on 6 February:

I decided to write Aubrey’s life in the form of a first-person diary. For a long time I didn’t tell anyone what I was doing in case they thought I had gone mad. I think good books result from taking risks. My advice to younger women is to write only about what most interests you, and if an agent or publisher tries to persuade you to write a safe book on a suitable topic, run as fast as you can from that poisoned apple.

Absolutely true, in my opinion, and I find my efforts strangely re-energised by thinking of myself as a ‘younger woman writer’!

Watch this Space 7 May 2016

7/5/16. The good news is that I have finished my fundamental revision of the biography. It can rest for a few weeks until I give it the final slow, close read. I turn now to writing the Introduction. These things are fantastically important, of course, and I have never been good at them. Over the last four years I have written two versions and binned both. There is a tendency to use the Introduction to witter with tightly clenched teeth about the things that bug the writer, rather than addressing the reader’s overwhelming question: ‘Why should I read your book?’ However, I go into it now with hope and some relish: there are nuggets from the earlier versions that are transferrable, and I have the extended written views of Clare Hopkins, Alison Miles, James Muckle, Harvey Pitcher, Karen Spink and Graeme Wright about what the Introduction should say. Thank you all, and if anyone else would like to advise me on this subject, please leave a Comment.

The results of my visit to the British Library last Wednesday may fairly be described as dramatic.

This is the cover of William Caine’s version of The Brave Little Tailor published in 1923 and dedicated to Kittie Calderon, with Caine’s explanation of the book’s provenance:

Unfortunately, I have never liked this book since a particularly histrionic master tried to read it to us at school. I not only do not find it funny, I find it squirmingly unfunny. But why do I, I asked myself during the writing of the biography. This is the question I have to address, because the book’s humour is typically Edwardian and, to a disarming extent, typically Calderonian. I had decided to analyse the problem in the Afterword, where I discuss George as an Edwardian and who the Edwardians were. I did not have to tangle with it in the body of the biography, I thought, because the book is not the work that George wrote and the latter had not survived…

But the manuscript I ‘discovered’ at the British Library is of the entire original three-act pantomime. Of this, 196 pages are in George’s hand, about fifteen in William Caine’s hand, and there are two complete typed copies. This is not only the sole dramatic manuscript of George Calderon known to exist, it is by far the longest extant manuscript of anything by him. Almost certainly, I should think, I am the first person to have read it since the project was cut short by the War in 1914.

As I read George’s beautifully fluent and legible hand, the mind-boggling task loomed of examining the script in detail, even comparing it line by line with Caine’s 1923 confection, writing several pages about it in the appropriate place in the body of the biography, and delaying the completion of the book by at least another two months. Dare I say it, this is a ‘discovery’ I could have done without at this stage.

But not so fast. The fact that over 90% of the manuscript is in George’s hand does not mean that all of that is by him. If what Caine says about his own contribution is true, the manuscript is probably just the fair copy made by George of the whole work after he had ‘cut and polished’ Caine’s ‘great many scenes’ (and there are five or so pages of revisions in Caine’s hand on this fair copy). In other words, it is still not possible to say what was created by George and what by Caine, so I am sticking to discussing the posthumous work in my Afterword. The manuscript and typescript raise many interesting questions, though. For instance, the ‘pantomime’ is renamed ‘A Musical Play’, and even ‘A Comic Opera’, in the typescript. It is wearisomely wordy and long, yet George gives its running time (without interval) as ‘2 hrs 7 mins’. This would be unbelievably short for such a word-monster in the theatre today, and confirms the impression from Pinero’s and Shaw’s plays, for instance, that Edwardian actors must have gabbled.

Among the four, undated letters from Kittie to Laurence Binyon conserved in the British Library, the most dramatic for me was a six-page one that I was able to date as 31 August 1920. It contains Kittie’s response to the first draft of Binyon’s ode in George’s memory. She particularly loved the last stanza: through ‘the whole of it […] he is there […] standing before one’. This letter contains a frank discussion of George’s character, from which I hope to be permitted to quote in my Afterword.

The final drama of my visit to the British Library was that I walked into a kind of brick curlicue as I was looking for a quick way out of its piazza. On analysis, I think the reason I was in a hurry is that I was desperate to flee the piazza’s terrible feng shui, by which I probably mean ‘pretentious all-brick architecture’. The medical results of my encounter explain the lateness of this and, probably, next week’s post, but I will be back!

Watch this Space 27 April 2016

27/4/16. By the time you read this, I shall either be poring over George Calderon’s uncatalogued manuscript (typescript?) of The Brave Little Tailor and Kittie’s letters to Laurence Binyon at the British Library, or I shall have done so, in which case I will be reporting on the results in next week’s post.

I have lost count of the number of archives I have worked in whilst researching this biography, but I have never worked in those at the British Library in Euston Road before. Frankly, I was rather relieved not to have had to, as some colleagues have found it a daunting experience. Either I have become Bewildered of Cambridge in my sixty-eighth year, or one has to be resigned to the website of a very large institution being complex; but I have been using computers for over thirty years and I do find the BL’s website labyrinthine and not very user-friendly. Again, I suppose a very large library has to cover every eventuality, but there are vast walls of words to get through. After taking well over an hour to pre-register as a Reader, receive email responses and register for a BL online account, I lost my way trying to pre-order my items and gave up.

But the staff are STELLAR! Once I had contacted PEOPLE in the Rare Books & Music Reference Service, and Western Manuscripts and Music Manuscripts, things moved at top speed. Not only did Andra Patterson, Curator of Music Manuscripts, find George’s manuscript in the voluminous uncatalogued Martin Shaw Collection — a feat in itself — and Zoe Stansell in the Manuscripts Reference Service clear my access to the Binyon Archive most unfustily, both immediately ordered the items for me on their own initiative and thus spared me the electronic quagmire. Bewildered of Cambridge cannot thank them enough for their fantastic service.

Since my last post, we have established from his military file that the first name of Onslow Ford, the fellow-officer of George’s in the 9th Ox & Bucks who knew Sir Ian Hamilton and wrote to him in July 1915 for news of George, was Wolfram. He was a portrait painter and moved in the highest social circles. I was able yesterday, then, to write a new paragraph for chapter 15, explaining that Hamilton was the source, or authority, for the idea that George might have been wounded, given first aid by the Turks, and become a prisoner.

Amongst Sir Ian Hamilton’s papers in the Liddell Hart Military Archives there are two letters pertaining to George’s fate. In the long one to Onslow Ford, Hamilton tells him that ‘one might fairly suggest there is quite a glimmer of hope still’ — and back in England Onslow Ford must have passed this on to Kittie. However, in the short letter that he wrote the same day to George’s commanding officer at the Third Battle of Krithia, Hamilton inadvertently refers to Kittie as George’s ‘widow’.

Meanwhile (see last week’s post) we are trying to trace descendants of the young man from Kennington, with a wife and children, who was killed by a landmine at Hythe in the year (1941) that Kittie stayed there, and whom Kittie probably knew…

I am fervently hoping that in the next seven days I shall be able to complete the penultimate revision of my typescript and proceed to writing the Introduction.

Watch this Space 20 April 2016

20/4/16. Several people have asked me about late photographs of Kittie. Here is the last one I know of. It was not easy to date. Triangulating from the probable year of Cairn terrier Bunty’s birth (1922), the dog’s known longevity, the garden furniture, the boundary hedge, and Kittie’s stouter appearance, I put it at 1936, possibly 1937. It seems strange that there are none later, considering that Kittie lived another fourteen years.

As followers know, I am stuck with 4% of George Calderon: Edwardian Genius still to revise, namely the last two chapters, covering Kittie’s life 1915-50. However, I am not as frazzled by this as I have been about missing deadlines in the past, since it is caused by ‘events’ — events that, hopefully, can only improve the book.

The Net has truly revolutionised biographical research. I do trawls every so often for new mentions of George and especially for archival material (obviously, much of this would never have been found before computers). The last one I did on 16 March. I was not expecting anything new, but collections in public archives are going online all the time. This trawl produced three astonishing new hits:

- The papers of Sir Ian Hamilton relating to his time in command of the Gallipoli campaign are held in the Liddell Hart Military Archives at King’s College London. A hit came up for an item catalogued as ‘1915 Jun 15-1915 Aug 8 Correspondence with relatives of soldiers relating to their requests for news of Lt George Calderon, 9 Bn Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, attached to King’s Own Scottish Borderers [and three others]’. Given the word ‘relatives’, I assumed this was a letter/letters from Kittie, especially as her maiden name was Hamilton and she could probably claim some relation. Wrong. Sir Ian had received a letter (which has not survived) from Onslow Ford, an officer who trained with George in the Ox and Bucks at Fort Brockhurst. Onslow Ford can be seen on the group photo I posted for 10 April 1915 and his name appears in a letter from Labouchere to Kittie that I quoted in my post for 15 July 1915. Labouchere told Kittie that Onslow Ford ‘knows Ian Hamilton and can write to him on the chances of [Edwardian expression] his being able to make special enquiries out there’. There was absolutely no evidence until now that Kittie took up Onslow Ford’s offer. On 8 August 1915 at GHQ, Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, Ian Hamilton dictated a substantial reply to Onslow Ford, which I cannot quote at length for copyright reasons but will summarise thus. Hamilton says that he has received nothing but ‘negative information’ about George’s whereabouts, but there have been ‘many cases’ of wounded officers being found with ‘first dressings’ put on them by the Turks, when trenches were retaken from the Turks after forward parties of British soldiers had occupied and lost them in the initial attack. Hamilton concludes, then, that there is ‘quite a glimmer of hope still’ that George Calderon will be found alive. So the idea that George was not killed outright, which Kittie clung to for another four years, originated with Sir Ian Hamilton himself. This is a rather sensational development and necessitates my re-writing part of chapter 15. There are several things I need to do, though, before I can proceed to that, e.g. discover the Christian name of Onslow Ford, which my indefatigable researcher Mike Welch is working on. Onslow Ford was one of the four sons of the Victorian sculptor Edward Onslow Ford, but we don’t know yet which one. Not the least intriguing thing, however, about the documents concerning George in this file is that Ian Hamilton dictated his reply to Onslow Ford on one of the very worst days for him, Hamilton, in the whole of the Gallipoli campaign. Hamilton had been despairingly watching offshore at Suvla the incompetence of his generals following the landings of the day before and had to intervene personally. He concludes his letter to Onslow Ford by apologising for its brevity, ‘but we are in the middle of a great battle’. Really, these Edwardians were extraordinary people…

2. ‘An Introduction to Martin Shaw’ is an article that appeared on the Web following the acquisition by the British Library of Shaw’s Archive from the firm of Quaritch, who wrote the original text. It mentions that Shaw’s papers contain ‘a rare manuscript by the young playwright George Calderon’. If true, it would not be rare, it would be unique! (George’s few extant dramatic relics are typescripts.) It is probably the text of George’s contribution to a pantomime called The Brave Little Tailor which he wrote with William Caine in 1913-14 and for which Shaw was writing the music. The pantomime text was completed, but not the music, because the War broke out and the project was aborted as it was based on a German fairytale. I couldn’t write about George’s text before, because it appeared to have been lost. Now I must see it, but the Shaw Archive at the British Library hasn’t been catalogued yet, so it will take curators a while to find it for me.

3. The papers of Laurence Binyon are on loan to the British Library (where, of course, he had worked when it was called the British Museum). There is a working catalogue of them online, but the BL search facility had not revealed any material relating to the Calderons. However, one of Binyon’s grandsons, Mr Edmund Gray, very kindly pointed out to me that ‘Calderon’ had been misspelt in the catalogue and there were in fact some letters from Kittie in his grandfather’s archive. I am very desirous to see them. They are probably from the period 1920-30 and may contain Kittie’s response to Laurence Binyon’s ode in George’s memory; in which case I will weave it into chapter 15 (Percy Lubbock’s response to it in a letter to Kittie was rather aspersive). The reason the archive has nothing from George is probably that he and Laurence Binyon often saw each other daily at the BM, and when they didn’t all that was needed was a note or a phone call to arrange to meet. Since Binyon’s papers are only on loan to the BL, I needed Mr Gray’s permission to access them, which he has most graciously given.

Finally, down at Kennington in Kent some very kind people contacted by local historian Robin Britcher (see ‘Watch this Space’ 24 February 2016) examined the records of St Mary’s Church for mentions of Kittie. (Understandably, there seems to be no-one alive there who remembers her.) They discovered that she was a founder member of the Friends of that church, who look after its fabric and pay for repairs/improvements. She was enrolled in 1941, paid her subscription for three years, and against her name was a full address in Hythe, twelve miles away. What was the significance of this? In 1941 Hythe was on the front line! Mike Welch established that the address had been a guest house in the 1920s, but it was impossible to discover from public records what it was during the war. Exercising his lateral thinking on the newly available information of the 1939 Register, however, Mike concluded that an unnamed child had been present in the house and might still be alive. He traced this child and I spoke to him, now aged eighty, on the phone. He confirmed that the house had been a popular guest house during the war, with many military families visiting, but in 1941 his grandparents decided to move inland as the shelling from across the Channel was hotting up. The guest house’s Visitors Book still exists, but stops in 1928. What was Kittie Calderon doing there in 1941 and how long did she stay? Could her visit be connected with the death of a young neighbour of hers, who was killed by a landmine on Hythe beach on 13 May 1941? The investigation continues, as does our search for a house in Torquay that Mrs Stewart, Nina Corbet’s mother, lived in for thirty years, and which Kittie visited for long periods after Nina’s death.

Altogether, an unexpected basinful…

Watch this Space 13 April 2016

13/4/16. The collective noun for emeritus professors is ‘a reticence’. It derives from the fact that although they still hold definite opinions, in retirement they are too shy to parade them before the world, e.g. in Comments that will appear on blogs. They prefer to communicate discreetly by email or word of mouth.

I have heard, then, from a reticence of professors emeriti in response to my post on 17 February 2016 about Laurence Binyon’s half-line ‘They shall grow not old’ and the controversy around Wilfred Owen’s poem ‘Dulce et decorum est’ (see ‘Archives’, bottom right, for February 2016, or click the link below and scroll down).

Half of the distinguished e.p.’s feel I ‘might have a point’ in suggesting that Binyon inverted the negative in his often misquoted line so that the ‘not’ seems to qualify the adjective ‘old’ as a luminous concept ‘not-old’, rather than adhering limply to the verb as ‘grow-not’. One former professor of English literature found my argument ‘utterly convincing’ and added that accepting the ‘simpler (and very banal) reading’ was ‘too easy’. Another said he ‘wished’ I was right, but felt that the public tendency to ‘correct’ the line to ‘They shall not grow old’ showed that Binyon had not succeeded in avoiding the impression that ‘he meant nothing subtler than to negate the verb’.

The same e.p. concluded: ‘It all depends on how you speak the line.’ Certainly it does. Personally, I find it nearly impossible to drop my voice enough to speak it as though it meant ‘grow-not old’, i.e. virtually elide the ‘not’ syllable or at least give the words three level stresses: ‘grōw nōt ōld’, as though ‘grow not’ was a spondee. Both seem to me totally unnatural to modern English. But perhaps that is the point: English, and English verse, are simply spoken differently from how they were in 1914.

One of the reasons the speaking of this half-line may have changed is that we expect poetry today to enact its meaning, rather than to be semantically coherent versified thoughts. Our way of reading poetry, I think, has been deeply influenced by today’s theatre, and particularly by the articulation of Shakespeare’s dramatic poetry since about the 1960s; not to mention by the poetry of G.M. Hopkins and Dylan Thomas. We aim not to declaim verse, but to create through the ear what is essentially a dramatic experience. Hence, in my view, we are not just telling that the fallen won’t grow old like the rest of us, we are showing it through the rising of ‘grow’ into the transfigured state ‘not-old’. The line is not just a statement, it has to get itself a life.

Of course, it may also be that an inverted negative — ‘grow not’ — is now so weird that we have simply forgotten how to speak it. Either way, the language has certainly moved on and in my view it has to take a poem like ‘For the Fallen’ with it. If it is really poetry, we cannot apply a purely historical, antiquarian approach to it and its reading.

One who would disagree with this, I fear, is the e.p. who told me, apropos of my attitude to ‘over-writing’ (Heaney’s phrase) in ‘Dulce et decorum est’: ‘It is not poetry’s job to be incoherent.’ I had never said it was. But I do not believe that poetry’s job is always to be coherent. One would be seriously misguided, I think, to expect unflagging coherence from poetry written by men like Wilfred Owen and Georg Trakl in the circumstances of which they were writing. I had suggested that the ‘incoherence’ of the ‘devil’s sick’ lines in Owen’s poem ‘perfectly enacts his horror’ in extremis. It enacts the breakdown of the man Owen in a place where, in his words, God seemed not to care. But I don’t think this particular e.p. would accept that enactive, dramatic view of poetry.

I recently found unexpected support for my take on incoherence in WW1 poetry in Drew Gilpin Faust’s superb book This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (Knopf, 2008). Faust explains that, contrary to Emily Dickinson’s image as a recluse, she was deeply engaged with the human cost of the Civil War. ‘She too sought to understand the meaning of war’s carnage, the price of victory and defeat, and the implications of Civil War slaughter for the Christian faith that shaped how most Americans lived their lives’ (pp. 205-06). ‘Marked by discontinuities’, Dickinson’s poems were posthumously assailed by ‘critics who deplored their travesties of grammar and syntax. But contemporary critics see in these attributes the embodiment of Dickinson’s doubts about the foundations of understanding and coherence’ (p. 208).

Some words of George Calderon’s come to mind, from a letter he wrote to Kittie on 11 April 1905 from Paris after an argument with Paul Boyer about anthropology: ‘He has the obedient professorial mind, which is ready to believe all manner of questions closed which are as open as hungry oysters.’

* * *

Next week I shall explain the archival and other issues that have been delaying my completion of the second typescript draft of my book George Calderon: Edwardian Genius. I am busy at the moment dealing with these and rewriting sections in the last two chapters, which deal with Kittie’s life 1915-50. I am also thinking a lot about the yet unwritten Introduction and Afterword.

Watch this Space 6 April 2016

6/4/16. I have now revised 96% of my book George Calderon: Edwardian Genius. The last chapter, covering Kittie’s life 1923-1950, feels too close still (I finished the second draft only two months ago) to tackle, so I am limiting myself to re-reading the very rich material that went into its making. Another reason for the delay is that I am waiting to view some new archival material that popped up only last month in the course of my regular trawls of the Web. I hope to post about that in two weeks time.

Meanwhile, it is still a rare pleasure to be able to draw followers’ attention to a commemoration that is not of those who ‘died as cattle’ in World War One, but of those who survived it and of the doctors, nurses and orderlies who enabled them to do so:

The First Eastern General Hospital (Territorial Force) was Cambridge’s outstanding contribution to the war effort, yet hardly anyone has heard of it today and there is nothing on its site to commemorate its existence.

It was a huge military hospital covering ten acres on the present-day sites of Clare College’s Memorial Court and Cambridge University Library. In a breathtakingly efficient act of collaboration between colleges, the War Office, Addenbrooke’s Hospital and local firms, work began in September 1914 on the construction of twelve 800-foot long huts comprising twenty-four wards with 1500 beds and the first patients were admitted on 17 October. The facility took in wounded, injured and sick from the B.E.F., the Mediterranean Force, the Home Force and Belgian casualties. It was a state of the art hospital (‘open-air’ for two years) and brilliantly run. Over 70,000 patients passed through it between 1914 and 1919 and it had an extraordinarily low death rate.

I heartily support the campaign to commemorate the doctors, nurses, VADS, orderlies, military personnel and teams of local people who created this amazing medical village, and the thousands of war victims whom they helped return to an active life. I commend the Appeal to followers of this blog. £25,000 is needed and at the time of writing £11,388 has been raised. Full information can be obtained at:

http://www.firsteasterngeneralhospital.co.uk/index.html

The memorial will be a large inscription hand cut by Cambridge’s Kindersley Workshop into the stonework of the outer wall of Clare College Memorial Court (this college owned most of the land on which First Eastern General was erected). The text will read: HERE IN THE FIRST EASTERN GENERAL HOSPITAL 70,000 CASUALTIES WERE TREATED BETWEEN 1914 AND 1919.

It seems particularly appropriate that the inscription should be designed and executed by the Kindersley Workshop, as David Kindersley (1915-1995) trained under Eric Gill (1882-1940), who was a major contributor to the style adopted for war memorials after WW1 and cut many himself. Kittie Calderon knew Eric Gill and adopted his apprentice Joseph Cribb as a correspondent and recipient of parcels from her when he went to the Front.

The full story of the hospital is told in the above book. Its title refers to the fact that the site started as a cricket field and ended as a copyright library. Between 1920 and 1929 it also provided emergency accommodation for 200 families at a time — the beginning of Cambridge’s social housing.

Philomena Guillebaud’s book is another gem of British local history (see ‘Watch this Space’ 2 March 2016). Rigorously researched, it is also lively, witty, and tells a profoundly inspiring story. In historical terms I was most interested to discover how far in advance of war the ‘shadow’ Territorial Force hospitals began to be assembled (1908). As Guillebaud puts it, the opening of First Eastern for admissions within ten weeks of the declaration of war ‘was no miracle: it was a remarkable case of successful forward planning’. The leadership of the hospital, principally surgeon Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Griffiths and matrons from Addenbrooke’s Hospital, was hugely impressive. Further proof, then, that the Edwardians were not the bumbling amateurs some may think.

This book may be obtained by sending a cheque for £14.00 (includes postage and packing) made out to Philomena Guillebaud at 26 Wilberforce Road, Cambridge CB3 0EQ.

Watch this Space 23 March 2016

23/3/16. I have now revised 92% of the typescript of my book. I shall tackle the last two chapters, which cover Kittie’s life 1915-50, after Easter. One reason for leaving them till then is that there are two pieces of new information that I am waiting for, which will probably have to go into the revision — there’s another kind of spanner that can affect one’s plans and deadlines! I will blog about these new items in a week or two.

The experience of revisiting chapter 14, which covers the last year of George’s life, was not so much dreadful (see last week’s post) as complex, and complex in an unexpected way. Yes, re-reading the extremely thick files on 1914 and 15 was draining, eviscerating at times; I was torn between not wanting to relive it and feeling I must relive it in order to ensure the revision was ‘fresh’. But actually I did not get caught by emotion more than two or three times whilst working on the chapter; I think what I was mainly experiencing was the brain remembering the pristine impact on me of these events in George’s life, and writing the first draft, rather than reliving them. I gather that that is how it works with injuries: you may appear to be struck down again by an injury you had years ago, but actually it is largely not the same, real pain but the brain being triggered by stress to ‘recall’ the pain. Anyhow the events as I revisited them were more at arm’s length, the revision was more dispassionate. This was a good thing, as when you are revising you really do need to stand further back from your text. Thus I spotted a number of things that I had skated over before, and was able (I think) to improve them.

The new thing that I found myself meditating as I revised the chapter was the extent to which, by singlemindedly propelling himself in 1914 and 1915 to the very most dangerous points in the war zones, George was consciously offering himself for ‘sacrifice’. Last year I considered the views that by signing up he was seeking ‘Adventure’, that he was suffering from Peter Pan Syndrome (‘to die will be an awfully big adventure’), that he was merely collecting material for a future book, or that he knew he was terminally ill and so his death was a kind of assisted suicide. But what if he believed that his highest duty was to sacrifice himself for ‘the cause of the free’, as Binyon puts it in ‘For the Fallen’?

In his classic work The Last Great War: British Society and the First World War (CUP, 2008), Adrian Gregory writes (p. 156) that ‘the idea of redemptive sacrifice was second nature to the [British] population, whether they realised it or not. […] Patri-passionism, the redemption of the world through the blood of soldiers, was the informal civic religion of wartime Britain’. But I have to say, I have never had that impression. It has always seemed to me that, whether amongst war poets, soldiers or the general population, the belief that self-sacrifice was glorious because it was needed to win the war did not come glibly or easily, it was hard wrung, delayed, and never accepted by some.

There is an outstanding example of what it could mean, though, in a book I have read recently, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (Knopf, 2008), by Drew Gilpin Faust. The American Civil War was in a way the first modern, ‘industrial’ war, and the effect of it on the American nation was similar at many points to that of the First World War on the British people. The young philosopher and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr volunteered to fight for the North out of certain moral beliefs, and went through the whole Civil War. Drew Gilpin Faust quotes intellectual historian Louis Menand to the effect that ‘the war did more than make Holmes lose those beliefs. It made him lose his belief in beliefs’. Obviously, it was exactly the same for many British soldiers, war poets, nurses and families. However, thirty years after the Civil War Holmes gave a speech entitled ‘Soldier’s Faith’ in which he said:

The faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has no notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

Drew Gilpin Faust (p. 270-71) paraphrases Holmes’s argument:

The very purposelessness of sacrifice created its purpose. In a world in which ‘commerce is the great power’ and the ‘man of wealth’ the great hero, the disinterestedness and selflessness of the soldier represented the highest ideal of a faith that depended on the actions not of God but of man. ‘War, when you are at it,’ Holmes admitted, ‘is horrible and dull. It is only when time has passed that you see that its message was divine.’

It was many years after his active service in WW1 that Stanley Spencer wrote of his altarpiece ‘The Resurrection of the Soldiers’ at Sandham Memorial Chapel: ‘The truth that the cross is supposed to symbolise in this picture is that nothing is lost where a sacrifice has been the result of a perfect understanding.’ Holmes’s and Spencer’s insight came with time. Like Owen’s uncharacteristic poem ‘Greater Love’, it was hard won. After surviving a WW1 battle you were unlikely to believe in ‘patri-passionism’.

I have never found a reference in George Calderon’s correspondence to ‘sacrificing’ himself for a cause or an end. There is no doubt that he insisted on being where the action was because he wanted Adventure, risk, a story to tell afterwards. He was prepared to drop all his considerable literary projects in 1914 for that.

But there is equally no doubt that he believed in what he was fighting for — freedom from brutal oppression. In my final chapter of his life I argue that he was also fighting for the new world order that he deeply believed would emerge from the war. Perhaps his own motivation did not go beyond that, but it is our Holmesian/Spencerian distance from events that makes it seem to us now that George was driven by self-sacrifice as an ideal.

A Happy Easter to all followers and visitors.

Watch this Space 16 March 2016

16/3/16. Segueing (I hope that is correct — I have never used the verb before) from last week’s post, I have to report three completely new developments that illustrate, I think, Jenny Hands’s thought-provoking Comment (see above right).

I had not heard the saying ‘you have to have a plan to be able to change it’ before, possibly because in writing, I find, you have not so much a plan as a conception, and that conception doesn’t live in your mind as a plan does, you live in the conception, which spontaneously grows till it’s ‘right’. However, I can well imagine that this saying is a truism in modern management, and in my experience the deadlines that form part of the project-plan of writing a book do operate as Jenny Hands suggests.

Last week I set myself the task of completing the revision of chapters 11 (‘Chekhov Is Such a Great Man…’) and 12 (The Trouble with Trade Unionism). The first task is to reread the entire file for the chapter, which leads to looking at some things from slightly different angles, revisiting some letters and documents, sometimes discovering entirely new, relevant things. I like to do it in a single, eight-hour or so sitting, so that I feel I’ve literally ‘got my head round it’, but it leaves the mind so tired you can’t start the actual revision until you have recovered, i.e. next morning.

The file for chapter 11 is particularly thick, but I managed to read half of it over the weekend, so that by last Monday morning I was ‘ahead’… Ah, but the revision of the beginning was particularly drastic and fiddly, because the discovery only last year of George’s 1907 diary threw wide open the question of whether George didn’t, perhaps, er, get the idea of translating The Seagull from Constance Garnett, whom he met for the first time that year and had problematical relations with later in the Stage Society. Even so, I finished that chapter (9119 words) by last Wednesday morning and went straight into chapter 12. That file is quite thin, because it is almost entirely factual rather than literary, and by the end of Thursday I had finished revising the chapter (5658 words) to my satisfaction. So I was a day ‘ahead’ of deadline!

Unfortunately:

1. I was so exhausted I knew it would be counter-productive to go straight into chapter 13, Wilder Shores of Translation (10,800 words and mesmerisingly literary). What you are after, of course, when you are revising a long work, is absolute consistency. It’s therefore vital to do the work on the same level of energy. You can sometimes spot — around the middle — when writers have begun to push themselves too hard with their revision/editing.

2. Followers may recall that the life-changing discovery last year that George had had a serious flirtation with philosophical Taoism led to my losing days and days in my rewriting of chapter 6 (26,896 words). I concluded the new section: ‘there are a number of small facts that suggest his interest in the Taoist view of life continued to at least 1912, and we shall note these in passing.’ When revising chapter 11, I pondered long the Taoist elements in two sections of George’s famous introduction to Chekhov’s plays, and settled for: ‘they both have distinct Taoist undertones.’ During Thursday night this began to niggle me, by Friday I had decided it was ridiculous — every reader would rightly be screaming ‘well what are they?!’ — so I spent the whole of this Monday reopening the Tao file, wrestling with these ‘undertones’, and explaining them in 300 words… Now, of course, I am behind schedule again. And I ought to add that on Friday I also came to the conclusion that in chapter 12 everyone would want to know what George’s party politics were, i.e. how he probably voted in elections, independently of his left of Centre personal political philosophy; so I would have to go back and grapple with that. But, fortunately, I decided it was better discussed in the Afterword…

3. As I contemplated revising chapter 13, Wilder Shores of Translation, I was suddenly struck by a dread of the one after that, covering 1914-15. This is because in its course chapter 13 focuses down on 1913. It returns the chronotope from four synchronic chapters (i.e. essentially thematic and covering the same period, 1907-12) to a linear timescale, i.e. traditional biography. Chapter 14 therefore begins with January 1914. Frankly, I slightly dread, even, starting work on 13. The dread is undoubtedly having a procrastinating effect. Working on 14, A New and Unknown Adventure, will be weird, as I not only had to live those draining events when I wrote it, I lived them from day to day when I was running Calderonia. I recall that I spoke about reliving the end in my post ‘The Dear Departed’ of 9 February 2015. It will be interesting to see how it turns out.

That is probably enough writerly introspection. Deadlines do get pushed all over the place. You never know in this game what is going to hit you next and put you ahead or days, weeks, months behind… But that’s right: it couldn’t happen unless you had a time-plan in the first place. Curiously, the very fact of writing this post about it may have changed the game and I shall tackle chapter 13 with fresh relish and even get ‘ahead’!

Note. There is a problem with double quotes in WordPress, hence only the title of chapter 11 above has been enclosed in inverted commas — the words here are George Calderon’s own.

Watch this Space 9 March 2016

9/3/16. At the time of writing, I have revised exactly two thirds of my typescript of George Calderon: Edwardian Genius, which I finished writing on 25 January. This means I am x weeks behind schedule, where x is somewhere between one and three.

I don’t know the exact number of weeks I am behind, I could work it out, but I have something more important to do: revising chapter 12, ‘The Trouble with Trade Unionism’!

On the one hand, it is depressing that all through this blog I have had to record missing self-imposed deadlines by weeks and even months, but actually it isn’t, you just have to accept that this is how writing is. You have to set yourself deadlines — at least, I find that I need a deadline breathing down my neck in order to get on with it — but if I have to exceed the deadline because there is new material to go in, or re-focussing is needed, or there is far more to check, or basically I need to take more care than I was expecting, that has got to be a good thing. I long ago reached the point where if I easily met a deadline, I was suspicious about what I’d written; it couldn’t be good enough, could it?

A very experienced journalist rang me yesterday, asked me how the book was going, and when I told him I was exasperated by the slowness he mollified: ‘But there’s no real hurry, is there? You don’t have to get it out by a particular time.’ This was music to my ears, but it still surprised me, as he is as used to working to deadlines as I am, and of course I had always wanted to get the biography out for the centenary of George’s death at Gallipoli. My friend’s argument, however, was that the new material that has come to light since I started writing the book has to go in. He has got a point. I won’t have a second chance, and I assume there won’t be another biography of George for a while…

Meanwhile, my blogmaster is designing Calderonia‘s next metamorphosis. This will contain all the back-numbers of ‘Watch this Space’, most Comments will be archived but they will all be easily accessible, it will be made easier than ever to leave a Comment, the links will be updated, and a number of Categories — overarching general terms such as ‘Edwardian Character’, ‘Heroism’, ‘War Poets’, ‘Edwardian Marriage’ — will be introduced. The changeover will happen on 10 April.

Watch this Space 24 February 2016

24/2/16. Local historians are the salt of the earth. They know their specialist area intimately and utterly. When the subjects of biographies settle for significant periods of time in different places, as George did at Eastcote, George and Kittie did at Hampstead, then Kittie did at Sheet and Kennington, without the help of local historians biographers would only scratch the surface of their lives in these places.

In the case of Eastcote, I was unbelievably lucky, because Karen Spink had already researched and published a terrific article about George’s time there (1898-1900) for the 1999 issue of the Journal of Ruislip, Northwood and Eastcote Local History Society (RNELHS). Karen twice walked me through the mile and a half of footpaths and road that George would have taken on his bicycle to get from his digs at Eastcote to catch the train at Pinner station on his way to the British Museum. She also showed me all over historic Eastcote and arranged for me to visit the private property where George lived. This is not to mention the endless sources she sent me about the life of Eastcote in those years. If my very large chapter two, ‘Eastcote Man’, has any deep texture apart from George’s love letters written from Eastcote to Kittie, it is entirely thanks to Karen, who also independently undertook to research the Calderons’ property in Hampstead.

Sheila Ayres of Camden History Society then helped Karen and me arrange a visit to two of the three private properties that once made up George and Kittie’s house in Hampstead. This was fascinating, as we had Kittie’s photograph album of 1902 to accompany us. The present owners were most welcoming and enthusiastic about the project.

My point about these wonderful local historians is not that they have spared me months and months of researching Eastcote and Hampstead that I would, of course, have been obliged to do myself, it is that I could never match their knowledge of these places and they have allowed me access to it with truly humbling generosity.

At Sheet in Hampshire a chance encounter led me to Vaughan Clarke, an historian who through his local contacts was able to confirm that the house I thought was where Kittie had lived 1922-34 was indeed ‘Kay’s Crib’ until its name was changed seventy years ago. Mr Clarke was also able to enlighten me about the social stratification of Sheet in the 1920s; this proved critical for working out why Kittie failed to ‘settle’ there. Mr Clarke is now Chairman of Petersfield Museum, which is well worth a visit. Each year the gallery of the museum exhibits a different selection of the painter Flora Twort (1893-1985), whom Kittie probably knew and who moved from Hampstead to Petersfield before her.

I have visited Kennington several times, and four years ago I placed appeals in local papers for anyone who still remembered Kittie to contact me (no-one did). For my last chapter, completed a month ago, I needed to get a feel for — to know as much as possible about –the life going on in Kennington outside Kittie’s windows at ‘White Raven’, where she lived from 1934 to 1948. I had over a hundred letters that she received in that period, about a dozen of her own, and many documents, but I needed as much context as possible. Here, the Ashford Archaeological and Historical Society have come to the rescue. Not only have they put feelers out amongst the senior population of Kennington, they are writing a piece about Kittie themselves for the Kentish Express. Amongst other things, this may settle the question of whether, as I think, The Cherry Orchard in George’s translation was performed at Ashford in 1940/41 as part of a campaign to raise money for the war effort.

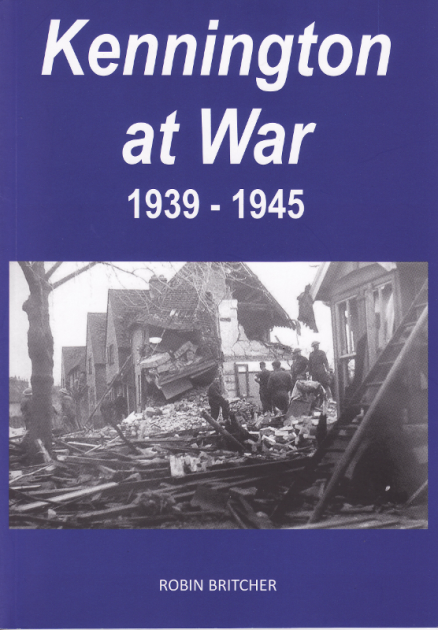

But above all, Robin Britcher, a member of the Ashford Archaeological and Historical Society, has spent ten years researching life at Kennington during World War 2, the result of which is this superb little book, published last month:

This book has provided absolutely critical local context to Kittie’s and Elizabeth’s lives at ‘White Raven’ during the war. Kittie wrote to Percy Lubbock in Montreux about every ten days and it is possible she mentioned to him some of the drama that was going on around her at Kennington, but maybe wartime censorship prevented her, and in any case her letters have not survived. Without Robin Britcher’s book, then, I would never have known that Kittie’s next-door neighbours were interned as enemy aliens, their house became a military nerve centre, a Heinkel bomber came down only a few hundred yards from ‘White Raven’, seventeen residents of Kennington died on active service, and nine bombs were dropped on the village killing two people, injuring others and wrecking homes. Kittie’s polite refusal of offers to accommodate her for the duration in places as far afield as Fife and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, takes on an even grittier edge.

However, Robin Britcher’s book is not only a portrait of Kennington during the war, it is an in-depth portrait of the village’s life as such: there is so much in it about the workings and personalities of the village that its usefulness for me extends beyond the war years. It is also very attractively presented, with masses of illustrations and an extremely well written text. I warmly recommend it. It can be bought directly from Mr Britcher at 169 Faversham Road, Kennington, Ashford, Kent TN24 9AE, by sending a cheque for £6.50 (includes postage and packing) made out to Robin Britcher.

I cannot help thinking that this country may have the best local historians in the world.

By the end of this week I shall have revised/rewritten about 58% of my biography of George. I have ‘lost’ a week because of the need to write a few new sections, particularly in the light of the sensational discovery last year of George’s pocket diary for 1907 — the only diary of his known.

This is the most recent ‘Watch this Space’ post. For the archive of ‘Watch this Space’, please click here.

Watch this Space 17 February 2016

17/2/16. The weekly digests of events in World War 1 keep coming in from The Times, every day the media run items and features connected with it, the public debate about commemorating the fallen continues. Although I left the field of battle, as it were, on 7 June 1915, there is no chance of getting away from the War. It gets to you…

I have no desire to revive the debate about commemoration, ‘making peace with the Great War’, empathy/sentimentality, ‘war porn’, historicisation etc — new visitors can see from Recent Comments, the archive of ‘Watch this Space’, and a search on ‘Commemoration’, how much we thrashed these subjects out last year, and that by December some of us felt we had said our last word. But with the Battle of Loos and the collapse of the Russians’ Polish front last autumn, the evacuation from Gallipoli last month, the battle for Verdun this month, and the Somme coming soon, one inevitably continues to mull issues. Perhaps since December some followers have acquired new angles on previous themes. Personally, I want to address only a small poetical matter, but I know it ‘ramifies’.

It’s common knowledge that line 13 of Laurence Binyon’s ‘For the Fallen’ is often recited as ‘They shall not grow old’, when it should be ‘They shall grow not old’. Is this done through mere forgetfulness or ignorance? I don’t think so.

If, as is natural, we assume that the words are expressing a plain negative, namely that the fallen, being dead, will not grow old, then we would expect the metrical, iambic stress to be on the negating word ‘not’: ‘They shall not grow old…’ In terms of subject and predicate, we could represent this as: ‘They shall not (grow old).’ However, that is not what Binyon has written. In his version the metrical stress is on ‘grow’: ‘They shall grow not old…’ The half-line therefore rises appropriately on ‘grow’. Grammatically, this might appear to be just an archaic inverted negative. But actually it makes ‘not’ an unstressed syllable, produces a slight pause after ‘grow’, and could be represented structurally as: ‘They shall grow (not old).’ In other words the movement of the line is towards making ‘not’ qualify ‘old’ rather than qualify ‘grow’. Growing into a state of not-oldness sounds odd, and I would suggest that it is this apparent non sequitur that causes readers to stumble and ‘correct’ the line to ‘They shall not grow old’.

However, if you read the line as Binyon wrote it, it seems to me inevitable that you visualise the fallen as growing into an affirmative new state of being ‘not-old’, and that this is what the poet intended. What could this state be? Well, transfiguration, immortality, glory. Glory is a very tricky word today, debased and even pejorative. I note that it is given fifteen different meanings in The Chambers Dictionary, ranging from ‘renown’ and ‘triumphant honour’ to ‘boastful or self-congratulatory spirit’ and ‘presence of God’. But the ‘not-old’ state of the fallen in Binyon’s poem reminds me of nothing so much as the lines from Henry Vaughan’s poem ‘They are all gone into the world of light’:

I see them walking in an air of glory,

Whose light doth trample on my days:

My days, which are at best but dull and hoary,

Mere glimmering and decays.

Most of Binyon’s poem is concrete and fastidious; but in ‘They shall grow not old’ I feel it approaches the transcendent dimension of Wilfred Owen’s ‘Greater Love’. The soldiers’ act of supreme love, namely their ‘ultimate sacrifice’ for others, has removed them to that place of transfiguration where ‘you may touch them not’ (Owen). By comparison, ‘we that are left’ live out days that are ‘but dull and hoary’, in Vaughan’s words.

Given that ‘For the Fallen’ is the most famous war poem in the English language, it is difficult to believe that this point has not been discussed, and analysed better than I can, many times before. However, I cannot find any discussion of it on the Web.

By contrast, you will find plenty of discussion on the Web of the second half of Wilfred Owen’s poem ‘Dulce et decorum est’, about a gas attack, and specifically of the line ‘His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin’. This discussion was possibly triggered by Seamus Heaney asking his students at Queen’s University whether the poem wasn’t ‘over-written’, ‘artistically bad’, and the lines in which ‘devil’s sick’ occurs weren’t ‘a bit insistent’, ‘a bit explicit’ (see his The Government of the Tongue, Faber & Faber, pp. xiv-xvi). Heaney seems to focus this into a conflict between ‘truth’ and ‘beauty’, ‘life’ and ‘art’, although his final take on the matter seems ambiguous; some might say specious.

The reason, in my view, that Owen’s words here are ‘over the top’ (‘If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood/Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,/Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud/Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues’) is that his reaction is naturally to use the strongest words he can find, this backfires on him, yet ultimately produces an incoherence that perfectly enacts his horror.

If you have read as many personal accounts of WW1 warfare as I have in the past year (Ypres and Gallipoli), you too become incoherent if you try to express your reaction to the horror and degradation of it. I cannot think that there has been another war in which the human savagery and sheer filth have reached these depths. We have to accept, which I think Heaney never really did, that ‘devil’s sick of sin’ etc is not an iota too strong for it.

The poles of our World War 1 poetry are ‘devil’s sick’ and ‘glory’. We are rightly being overwhelmed by the former in these anniversary years, but we must never forget the latter either. Apparently it was Lloyd George who proposed the words ‘The Glorious Dead’ on the sides of Lutyens’s Cenotaph. If so, he was a genius, but so many contemporaries were involved in the post-war memorialisation that I expect it was really a consensus. There is no ‘To’ in it, just the three words, as if to mean ‘This says all we can about them’. It is an age removed from Rupert Brooke’s understandably tawdry line of autumn 1914 ‘Blow out, you bugles, over the rich Dead!’. After our protracted, ‘wordy’ discussions of Commemoration last year, a follower of Calderonia emailed me that it was all very interesting but ‘The Glorious Dead’ remained; that was in a way all that could be said…

‘Lapidary verse’ is an interesting, classical art (Philip Larkin and Ted Hughes produced notable inscriptions for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee), and perhaps this recent anonymous example drives at what I have been trying to say:

EPITAPH

Their uniforms of shit

their lives of shit

their deaths of shit

we live.

What means forget

THE GLORIOUS DEAD?

I should inform new visitors to the blog that Laurence Binyon was a lifetime friend of George Calderon’s and wrote an ode In Memory of George Calderon whose last verse bears a resemblance to the final lines of ‘For the Fallen’.

I am currently revising Chapter 6, ‘Russianist, Novelist, Cartoonist’, which at sixty-five printout-pages is by far the longest. It covers the years 1900-1905. I keep thinking I must split it, but it is really the backbone of the book, because it attempts to show from analysis of George’s essays and novels that he is a first-rate Russianist and a significant Edwardian writer… Unfortunately, following discoveries in the last year I have to add 500 words to it about George and Taoism. The research and evaluation have been done, but it’s still going to be difficult to know where to splice this subject in. I will then have edited/rewritten nearly half of the book.

Watch this Space 10 February 2016

10/6/16. In a recent article in The Times, Richard Morrison complained that the 14-18 NOW commemorations (‘Extraordinary art experiences connecting people with the First World War’) that have been unveiled for 2016 show a ‘pretty tenuous’ link with the realities of the War; one case, he suggested, was even ‘a spurious gimmick’. ‘It’s ironic’, he continued, ‘that the commemoration that has made most impact so far — five million visitors in four months — wasn’t even part of 14-18 NOW.’ He was referring, of course, to the installation by Paul Cummins and Tom Piper at the Tower of London called Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red.

Setting aside private and local commemorations, which Morrison thinks are best, I know only one artefact so far in the 1914-18 commemorations that is in the Cummins-Piper league, and that is the project by Andrew Tatham called A Group Photograph (which was also not funded by the Arts Council).

Ten years ago my wife and I were in Norfolk and decided to visit some local exhibitions in the ‘Open Studios’ scheme. At Andrew Tatham’s house he directed us to the bottom of his garden, where there was a very small, but light-proof shed. In there, completely alone, we watched an animated film. It is no exaggeration to say that we stumbled out into the light afterwards lost for words.

This film shows the family trees of all the soldiers in a 1915 photograph growing, in Andrew’s words,

over 136 years, mixed in with photos of their families and historical time markers and contemporary music for each year, as well as with cycles of the moon and the seasons. Each of their trees grows like a real tree, with a trunk for each man and branches appearing for children, grandchildren and so on down the generations. There is a baby’s cry for each birth, and a bell toll for each death. You can vividly see the immediate effect of the War on this group of men and get a view on the aftermath.

The film has developed since then, but always been at the heart of what I would call Tatham’s ‘whole-life commemorative installation’, which has gone on for more than twenty years in the form of presentations and talks all over Britain, exhibitions, notably in the Cloth Hall at Ypres in 2015, vibrant media interviews, and now the book:

I will say no more about the nature of this amazing project, but recommend to followers that they go to Andrew Tatham’s own explanation of it: http://www.groupphoto.co.uk/ .

The profundity of A Group Photograph comes from the fact that it evokes the lives and deaths not only of the forty-six members of the 8th Battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment, whose commanding officer was Tatham’s great-grandfather, but of the families and friends around them, and their descendants to this day, scores of whom have been intimately involved in the project. It brings history and the present together in a supremely palpable way. It is both War and Peace — and the creation of this continuum is, ultimately, a source of hope to those who experience it through Tatham’s work.

The book, which is beautifully illustrated and very reasonably priced, is prefaced with a poem by Tatham that traces in brief images how he became drawn into the project. The last stanza reads: ‘And now I search/That picture of men in a war/I see today and yesterday/I cannot forget.’ The last two lines say it all.

At the time of writing, I have completed the ‘final edit’ of 17% of my biography of George Calderon. So I might finish the work in another three weeks… Engaging with chapter 2, which narrates from day to day his love affair with Katharine Ripley (i.e. Kittie), was exhausting. I had to get the letters out again to check quotations, and had forgotten how intense, claustrophobic and full of mood swings the relationship was.

Watch this Space 3 February 2016

3/2/16. Today I tackle the revision of chapter one, first written, revised and wordprocessed in June 2011. I have always known it was going to be a challenge, as it starts the biography at one remove (George hardly appears in it) and the first page and a half is too philosophical, airy-fairy and drawn out… It’s a terrible beginning if you want to grab the reader and never let them go again. At the time of writing I tried to get round this by keeping it very short (3500 words), but that was fudgery… There are things in it that are important (to me) to say, e.g. about Edwardian semantics and body language, not to mention Kittie’s first husband and George’s university friend Archie Ripley, but no publisher, I fear, will want it; or the last chapter. Chekhov’s advice is ringing in my ears: ‘when you have written a story, tear off the beginning and end of it, because that’s where we writers lie most’!

A number of followers have asked me what condition Kittie was suffering from in her years at ‘White Raven’ (1934-47) and whether it was this that carried her off (30 January 1950).

The latter is the easy question. On her death certificate the causes of death are given as: 1a Hypostatic Pneumonia, b Cardiac failure, c Arteriosclerosis. However, her hypostatic pneumonia (‘Old People’s Friend’) was just the result of prolonged confinement to bed (constant fluid collection at back of lungs), ‘cardiac failure’ refers presumably to her heart winding down, and ‘arteriosclerosis’ was a long-term condition, so it seems to me these amount to saying no more than that the cause of death was ‘old age’ and they tell us nothing about her chronic health problems 1934-47.

The most obvious reason for all her correspondence suddenly breaking off in 1946 is that she had a stroke and never recovered the ability to write. But there is no independent evidence for this and she does not seem to have entirely lost her powers of speech. I don’t favour this explanation, therefore. The ‘most obvious reason’ for no letters from or to Kittie having survived after 2 January 1946 is actually that they were lost or burned after her death! Given the large number of her correspondents, it is hardly likely that they all stopped writing to her at once. (On the other hand, if she did have an incapacitating stroke all her correspondence would have been taken over by her attorney, Louise Rosales, and Mrs Rosales was definitely a ‘burner’.)

Kittie’s known symptoms after moving into White Raven were problems with (close?) vision, suddenly falling asleep, and having to keep running to the ‘bathroom’. Not a single photograph of her wearing glasses is known, but we know she had them as she refers in a diary to her ‘spex’. But the problem was not just optometric. She visited a consultant in London, who it seems told her he could do nothing for her beyond a new lense prescription. This implies that the real problem was cataracts or something like macular degeneration. Her suddenly ‘falling asleep’ could have been just a hypothermic reaction to inactivity in the grossly underheated houses she lived in. Although Kittie says in a private letter that it is her ‘middle’ that plays her up, implying the problem is gastric, her spidery failing writing and blackouts could imply chronic urinary tract infection. She thought very highly of her G.P. in Ashford, a Dr Body (!), and he tried the latest medication for her gastric/urinary condition, but it didn’t work.

We shall probably never know what Kittie clinically had wrong with her. But the really interesting thing, in my view, is that nowhere does Kittie ever say what, clinically, she has been diagnosed as having. This, I think, is very characteristic of the Edwardians and, indeed, our recent forebears. You did not name your disease/complaint, because (a) medical terminology was for doctors, (b) you weren’t supposed to discuss illness openly, (c) your job was to keep a stiff upper lip through it all.

There is a graphic illustration of Kittie’s attitude to illness in her pocket diary for 1939 — and incidentally it shows that we must add the term ‘grip’ to ‘staunch’, ‘stalwart’ and ‘stout’ in our Edwardian vocabulary. She had had a fall in September or November 1938 (she is confused about which) and been badly concussed. This had aggravated her already existing proneness to falling asleep. But she was determined to battle on, and to write about it in her diary for 10 January 1939 even though this cost her great effort and her writing and self-expression were affected:

Returning from Foxwold tomorrow [=yesterday, 9 January]. I found E. [Elizabeth Ellis?] better but not quite well. Came as far as Maidstone with E. [Elizabeth Pym?] then fetched by [illegible name] Gar. [probably ‘Garage’ at which chauffeur worked, in Kennington, Ashford]. Frightfully tired seems absurd to be so tired suppose its still after Xmas tiredness in spite of doing nothing at Foxwold and never down till lunch[.] But difficulty getting to bed till small hrs as would fall asleep in chair and wake about three – seems as if sitting down to take off my stockings is the moment that sleep gets me like a descending lid on a box and I wake about 3 to 4. Sometimes it would be a letter I had to write – I’d only get a few wds written[.] The only safe time to catch a post at Foxwold is the early morning post man. I’ve no warning of feeling ‘sleepy’ – just as I say a sudden lid shuts down. When first this used to occasionally happen Dr Carver [Mrs Stewart’s doctor in Torquay] said it was a form of Exhaustion and I must regard it as heaven sent – but since this dunt on my head on Sept. 5th it seems to be perpetually happening. Still I daresay heaven sent but difficult to deal with must try to do less somehow – but goodness knows how – I was really doing ‘nothing’ at Foxwold but yet so tired when I got to my room (not feeling tired) that apparently the lid would shut down with no warning and I went to sleep [f]or 3 or 4 hrs. […] I pray nightly for return of ‘grip’ after Prayer for Peace.

She had recovered by the beginning of March and was following political developments in Europe closely. Two months before war broke out she was able to revisit her birthplace, St Ernan’s Island Donegal, on a motoring holiday with Louise Rosales.

Watch this Space 25 January 2016

25/1/16. As many have said before me, the agony of ‘writing’ is the fight to the death between what you think you want to say and…the writing. It is draining, torturingly slow, and I’ve had weeks of it with ‘White Raven’, the sixteenth and last chapter of my biography of George Calderon. Now it’s over. Today I ‘finished’ the book. All that I have to do is revise it (164,000 words), add about 800 words, write the Introduction and Afterword, Acknowledgements and Bibliography, etc., which will probably take two months! Despite the nervous exhaustion, I cannot help but feel light-headed.

A blog-visitor asks me whether ‘completion’ will leave me feeling ‘as if you are missing something close to you’. I have thought about this and I believe the answer is no. I have been writing the biography sensu stricto for four and a half years, but one way and another I’ve been in a dialogue with George and Kittie for over thirty. They are locked in my heart and mind; the key is lost; they will be there for ever.

But I cannot pretend that I have said goodbye (in writing, at least) to Kittie today without a deep sadness — a malaise quite different from the terrible, senseless wrench of George’s death at Gallipoli two chapters before. Thanks to her three diaries and the far more extensive documentary material than in George’s case, I had been living and dreaming her life at White Raven — a house I know well — almost day by day between 1934 and 1944. It is sad that she gave herself so completely to other people in this period, some of whom appallingly exploited her, that she kept the ailing Elizabeth Ellis on as her housekeeper through thick and thin, took Elizabeth to Hove with her, even, where they died eighteen months apart in the same nursing home, that hardly anyone was present at Kittie’s funeral, and that we don’t even know where her ashes were scattered. Yet this is how she planned it. There can be no doubt that her last years were a determined kenosis.

During the war, when she could not sleep at night because of the air raids, she sat in an armchair by her bed ‘very tightly wrapped up in a travelling rug’ (Edward Hamilton), going through all her and George’s boxes of papers, dividing them into those to be burned and those to be saved for posterity. She captioned most of her 525 photographs and wrote explanations or comments on many of the 884 letters. These explanations are clearly addressed to someone unnamed who will be listening — someone in the future. Against all the odds (for by 1950 George was publicly almost forgotten) she believed someone would hear her. I feel endlessly honoured to be the first such person.

About fifteen times whilst writing this last chapter I considered heading it with a quotation from a letter of Percy Lubbock’s written in 1944. Percy had been exiled from Italy with his wife Sybil since 1940, Sybil died in Montreux at the end of 1943, and Percy was left alone there for the rest of the war. Kittie had sustained him with her regular letters evoking Lubbock family news and life at Foxwold more vividly, visually, he told her, than anyone else. He and she had a pact that if he could not cope as Sybil’s tropical disease worsened, Kittie would fly to Switzerland immediately; but in the event, this was militarily impossible. On 26 April 1944 he wrote to her: ‘I clearly see you from afar, but you are a long way off.’ This exactly expresses my own feeling as I was writing the end of the book. But epigraphs like this can be toxic. I decided against it.

After a break, I shall start ‘re-writing’ the book I have just ‘finished’, and I will be posting weekly on a wide range of topics.

Watch this Space 15 January 2016

15/1/16. One of the most difficult problems of researching Kittie Calderon’s life after George’s death is deciding how much she travelled abroad. After Percy Lubbock married Lady Sybil Cuffe in 1926, the couple lived in the fabulous Villa Medici at Fiesole and invited Kittie to stay with them at least six times between 1928 and 1930; but she seems to have gone only once (in November 1930). Similarly, she twice planned to visit Constantinople and Gallipoli, but the evidence is that she did not.

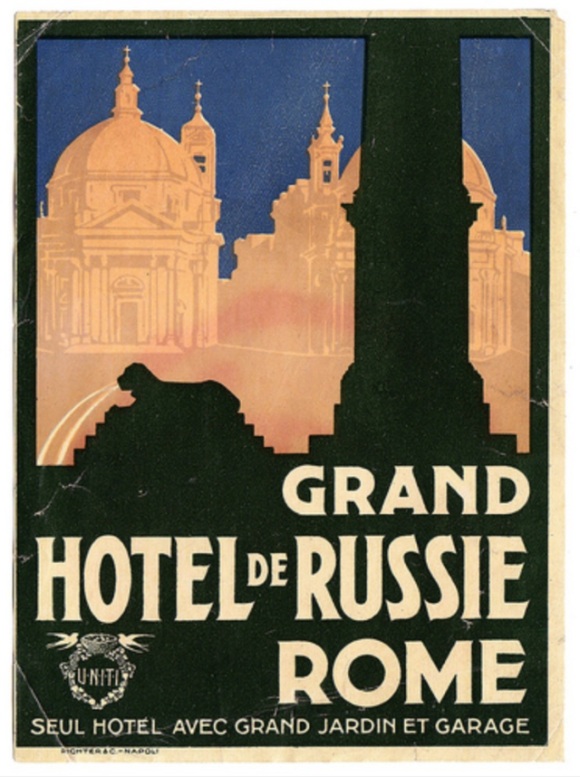

There is a fine leather suitcase emblazoned ‘Mrs. George Calderon’, which has the remains of a single foreign luggage label on it:

I cast an eye over this label twenty years ago and thought: ‘Hm, “Russie” down right, a minaret top left, must be from travelling to Constantinople by ship, which was also a route to Russia’. But last week, having concluded Kittie did not go to Gallipoli, I took a closer look at the label (with a magnifying glass). First, as the image above clearly shows, top left is not a minaret, but a dome topped with a cross. The only church it reminded me of from my own experience was the basilica of Le Sacré Coeur in Paris. Second, what could the letters RAND be a part of, if not a French place name? I assumed that the letter before the R was an E, then ran through the possibles. None was at all convincing. Then the penny dropped: it is much more likely to be a G before RAND — and grand must be the commonest word ending in -and in the French language. Googling about on ‘le grand‘, Paris and ‘Russie’, I eventually came up with the Grand Hôtel de Russie at the top of the Boulevard Montmartre in the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries. The Sacré Coeur basilica would tally with that, of course.

As far as is known, Kittie went to Paris only once, with George on their honeymoon in 1900. Both were keenly interested in contemporary French painting, which might explain why they stayed in Montmartre, and they may well have known that the famous series of paintings of Boulevard Montmartre by Impressionist Camille Pissarro was made from his balcony in the Grand Hôtel de Russie. The ‘suitcase’ is actually more like an attaché case of the period, i.e. hand luggage. The prominent words ‘Mrs. George Calderon’ on the front might be there because Kittie was going to Paris and wanted to make it clear she was (newly) married… At least, that is my hypothesis: that this case is her honeymoon case.

Other hypotheses that would explain this label are invited! Note that I am unable to explain the black, column-like shape on the right, or the bit of shield at bottom left that appears to say UNIT[É?].

Stop Press!

16/1/16. Within hours of the above post going up, John Pym emailed me with an image he had found on the Web of a luggage label that fitted Kittie’s exactly and demonstrates that the hotel was in Rome, not Paris. The only difference was that the image did not feature the UNIT[…] shield bottom left. However, it was conclusive proof that the label could not date from George and Kittie’s honeymoon to Paris in 1900. I had actually found the Grand Hôtel de Russie in Rome when I was trying to identify Kittie’s label, but rejected it as the nearest church had no high pinnacles on it, whereas the basilica of the Sacré Coeur in Montmartre has… I hadn’t considered the Vatican!

Well, by the evening Calderonia‘s indefatigable Web-Meisterin Katy George had found and sent me an even better image:

This contains the logo U.N.I.T.I. and even an extra line, again in French. If I had offered a bottle of champagne, Katy would definitely have won it! My sincere and humble thanks to her, to John Pym, and others who emailed me about this yesterday. My thanks are very humble, because I never expected so many people to give their time so generously to solving this one and my own hypothesis was up a gum-tree…

I have been asked when, then, did Kittie visit Rome? Most likely in 1930, when she stayed with Percy and Sybil Lubbock at Fiesole, whence it would be easy to reach Rome by train, but possibly the year before: a scrap of label on the side of her case says LUG, most likely standing for LUGANO, which might refer to a possible visit to Lesbia Corbet (married name Mylius) on Lake Como in 1929. Whereas the Grand Hôtel de Russie in Montmartre seems to have gone long ago, the one in Rome appears to have survived to this day — minus the ‘Grand’.

Thanks again to everyone who responded so splendidly.

Watch this Space 1 January 2016

1/1/16. A very happy new year to everyone. As you will gather from the above, we are now presenting Calderonia slightly differently. ‘Featured Comments’ will soon replace ‘Comments’, although all past Comments will still be accessible. Links will be introduced between past Comments and it will, of course, be possible to leave new ones. Previous ‘Watch this Space’ posts will be archived and made accessible. A number of over-arching categories that are not tagged, e.g. ‘Edwardian Character’, ‘Conduct of the War’, ‘War Poets’, will also be introduced. I shall leave up ‘Christmas at “White Raven” 1944’ for a little longer, as people have emailed me that they like it. Then it will be archived. I hope to carry on posting weekly until the biography is published, and I may feature some entries from Kittie’s diary for ninety years ago on the days for which she wrote them. Watch this space for completion of the last chapter of the biography very soon.

Watch this Space 24 December 2015

(Christmas at ‘White Raven’, 1944)

Faithful followers of this blog/website will recall twelve months ago the Christmas of 1914 at Foxwold, Brasted Chart, in Kent. The Pym, Lubbock and Calderon families all participated, as well as two refugees from German-occupied Belgium who were living with George and Kittie Calderon in Hampstead. None present ever forgot it, and Percy Lubbock wrote poignantly of it in his portrait of George published in 1921.

The only other Christmas in Kittie’s life after 1914 that we have as much information about is that of 1944, thirty years later when she was seventy-seven. That too was dramatic, but in a completely different way. I felt it would be appropriate, before the year in which my biography should be published and this blog ends, to describe from manuscript sources what happened at Christmas 1944.

* * *

My deeper research into Kittie’s life at Sheet, Petersfield, persuades me that she made the mistake in 1922 of coming in at the very top of local society. She was a relation by marriage and good friend to the biggest local landowner, Helen Bonham-Carter (then hyphenated); she was the widow of a war hero and literary man whose public profile was still quite high through the 1920s; she was the scion of a famous family (the Irish Hamiltons); and she had exalted friends (Astleys, Corbets, Ripleys etc) who visited her. Yet she lived in a relatively modest Victorian cottage, ‘Kay’s Crib’, outside the village proper. Much of the rest of Sheet society was composed of upper middle class retired folk, e.g. from the military, who rather fancied themselves. Understandably, when Kittie hove in she put these people’s backs up. She described Sheet in retrospect as ‘my prison’.

By about 1932, Kittie had decided to get out of Hampshire. Her nephew Edward Pakenham Hamilton (1893-1983) had become Estate Manager at Godinton Park, near Ashford in Kent, and his father, Kittie’s only brother John Pakenham Hamilton (1861-1946), had moved to Ashford with his wife to be close to their eldest son. This, and the desire to be nearer to the Pyms at Foxwold, persuaded Kittie to buy a plot of land north of Ashford and have a house built there according to her own specifications. She asked Violet and Evey Pym’s son, the architect John Pym (1908-93), to build it for her, and she moved into it in late 1934. John Pym’s brother, the artist Roland Pym (1910-2006), then painted the above white raven over the door, as that was to be the new house’s name.

‘White Raven’ was the sobriquet she had adopted in her relationship with Caroline (Nina) Corbet (1867-1921), who was ‘Black Raven’ because her first husband was Walter Corbet (1856-1910), descended from a henchman of William the Conqueror’s called ‘Le Corbeau’.

Unlike ‘Kay’s Crib’ in Sheet, Kittie settled into ‘White Raven’ extremely well. She designed a formal garden and took on a gardener called Grant. Although at that time ‘White Raven’ was in relatively open countryside, she was in easy distance of a church and village, and beyond that was Ashford with its fast line to London. The people who lived around her were far more middle class than at Sheet and she became something of a local treasure. She was visited by friends from her earlier life (probably including Sir Coote Hedley, the ‘Godfather in War’ (q.v.), who died in 1937) and often saw her brother John and nephew Edward. By April 1942, however, Edward Hamilton had had to move to a job at Retford.